A Problem From Hell: America and the Age of Genocide (55 page)

Read A Problem From Hell: America and the Age of Genocide Online

Authors: Samantha Power

Tags: #International Security, #International Relations, #Social Science, #Holocaust, #Violence in Society, #20th Century, #Political Freedom & Security, #General, #United States, #Genocide, #Political Science, #History

Minutes after the phone call a UN peacekeeper attempted to hike the prime minister over the wall separating their compounds. When Leader heard shots fired, she urged the peacekeeper to abandon the effort. "They can see you!" she shouted. Uwilingiyimana managed to slip with her husband and children into another compound, which was occupied by the UN Development Program. But the militiamen hunted them down in the yard, where the couple surrendered. There were more shots. Leader recalls, "We heard her screaming and then, suddenly, after the gunfire, the screaming stopped, and we heard people cheering." Hutu gunmen in the presidential guard that day systematically tracked down and eliminated virtually all of Rwanda's moderate politicians.

The raid on Uwilingiyimana's compound not only cost Rwanda a prominent supporter of peace and power-sharing, but it also triggered the collapse of Dallaire's UN mission. In keeping with a prior plan, Hutu soldiers rounded up the peacekeepers at Uwilingiyimana's home, took them to a military camp, led the Ghanaians to safety, and then killed and savagely mutilated the ten Belgians. Because the United States had retreated from Somalia after the deaths of eighteen U.S. soldiers, the Hutu assailants believed this massacre would prompt a Belgian withdrawal. And indeed, in Belgium the cry for either expanding UNAMIR's mandate or immediately pulling out was prompt and loud.

Only at 9 p.m. on April 7 did Dallaire learn that the Belgians had been killed. He traveled to Kigali Hospital, where more than 1,000 dead Rwandan bodies had already been gathered. Dallaire entered the darkened morgue and shone his flashlight on the corpses of his men, who were heaped in a pile. At first he wondered why there were eleven bodies when he had been told that ten were killed. Then he realized that their bodies had been so badly cut up that they had become impossible to count. Dallaire negotiated with the Rwandan authorities to lay their corpses out with more dignity and to preserve what was left of their uniforms.

Most in the Pentagon greeted the news of the Belgians' death as proof that the UN mission in Rwanda had gone from being a "Somalia waiting to happen" to a Somalia that was happening. For many, the incident fed on and fueled ingrained biases about UN peacekeeping because the Belgians had allowed themselves to be disarmed. James Woods, deputy assistant secretary of defense for Africa since 1986, recalled:

Well, there was horror and consternation at the deaths and, particularly, that they died badly. But there was also consternation that they did not defend themselves.They did not draw their pistols. I think it tended to confirm in the minds of those people who were following UN peace operations that there was a lot of romantic nonsense built into some of the ground rules and this was another reason to steer clear of UN peacekeeping operations.... I heard one person say, "Well, at least, you know, our rangers died fighting in Somalia.These guys, with their blue berets, were slaughtered without getting a shot off.',

A fever descended upon Rwanda. Lists of victims had been prepared ahead of time. That much was clear from the Radio Mille Collines broadcasts, which read the names, addresses, and license plate numbers of Tutsi and moderate Hutu. "I listened to [it]," one survivor recalled, "because if you were mentioned over the airways, you were sure to be carted off a short time later by the Interahamwe.You knew you had to change your address at once"°

In response to the initial killings by the Hutu government,Tutsi rebels of the Rwandan Patriotic Front, stationed in Kigali under the terms of a recent peace accord, surged out of their barracks and resumed their civil war against the Hutu regime. But under the cover of that war were early and strong indications that systematic genocide was taking place. From April 7 onward, the Hutu-controlled army, the gendarmerie, and the militias worked together to wipe out Rwanda's Tutsi. Many of the early Tutsi victims found themselves specifically, not spontaneously, pursued. A survivor of a massacre at a hospital in Kibuye reported that he heard a list read over a loudspeaker before the attack began. Another survivor said that once the killing was finished:

They sent people in among the bodies to verify who was dead. They said," Here is the treasurer and his wife and daughter, but where is the younger child?" Or, "Here is Josue's father, his wife and mother, but where is he?"And then, in the days after, they tried to hunt you down if they thought you were still alive.They would shout out," Hey Josue, we see you now" to make you jump and try to run so that they could see you move and get you more easily.'

In Kigali in the early days, the killers were well-equipped government soldiers and militiamen who relied mainly on automatic weapons and grenades. In the countryside, where the slaughter gradually spread, the killing was done at first with firearms, but as more Hutu joined in the weapons became increasingly unsophisticated-knives, machetes, spears, and the traditional masu, bulky clubs with nails protruding from them. Later screwdrivers, hammers, and bicycle handlebars were added to the arsenal. Killers often carried a weapon in one hand and a transistor radio piping murder commands in the other.

Tens of thousands of Tutsi fled their homes in panic and were snared and butchered at checkpoints. Little care was given to their disposal. Some were shoveled into landfills. Human flesh rotted in the sunshine. In churches bodies mingled with scattered hosts. If the killers had taken the time to tend to sanitation, it would have slowed their efforts to "sanitize" their country.

Because the H atu and Tutsi had lived intermingled and, in many instances, intermarried, the outbreak of killing forced Hutu and Tutsi friends and relatives into life-altering decisions about whether or not to desert their loved ones in order to save their own lives. At Mugonero Church in the town of Kibuye, two Hutu sisters, each married to a Tutsi husband, faced such a choice. One of the women decided to die with her husband. The other, who hoped to save the lives of her eleven children, chose to leave. Because her husband was Tutsi, her children had been categorized as Tutsi and thus were technically forbidden to live. But the machete-wielding Hutu attackers had assured the woman that the children would be permitted to depart safely if she agreed to accompany them. When the woman stepped out of the church, however, she saw the assailants butcher eight of the eleven children. The youngest, a child of three years old, pleaded for his life after seeing his brothers and sisters slain. "Please don't kill nie," he said. "I'll never be Tutsi again." But the killers, unblinking, struck him down.'

The Rwandan genocide would prove to be the fastest, most efficient killing spree of the twentieth century. In 100 days, some 800,000 Tutsi and politically moderate Hutu were murdered. The United States did almost nothing to try to stop it. Ahead of the April 6 plane crash, the United States ignored extensive early warnings about imminent mass violence. It denied Belgian requests to reinforce the peacekeeping mission. When the massacres started, not only did the Clinton administration not send troops to Rwanda to contest the slaughter, but it refused countless other options. President Clinton did not convene a single meeting of his senior foreign policy advisers to discuss U.S. options for Rwanda. His top aides rarely condemned the slaughter. The United States did not deploy its technical assets to jam Rwandan hate radio, and it did not lobby to have the genocidal Rwandan government's ambassador expelled from the United Nations. Those steps that the United States did take had deadly repercussions. Washington demanded the withdrawal of UN peacekeepers from Rwanda and then refused to authorize the deployment of UN reinforcements. Remembering Somalia and hearing no American demands for intervention, President Clinton and his advisers knew that the military and political risks of involving the United States in a bloody conflict in central Africa were great, yet there were no costs to avoiding Rwanda altogether. Thus, the United States again stood on the sidelines.

Warning

Background: The UN Deployment

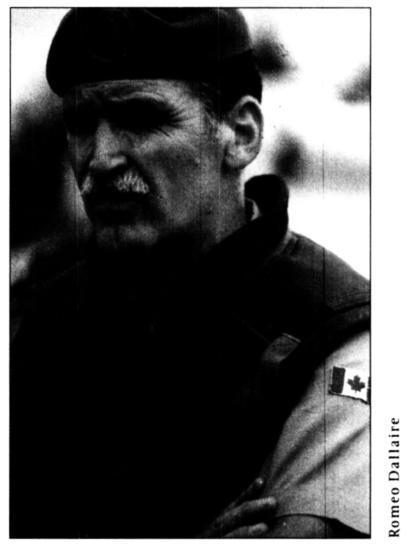

If ever there was a peacekeeper who believed wholeheartedly in the promise of humanitarian action, it was the forty-seven-year-old major general who commanded UN peacekeepers in Rwanda. A broad-shouldered French Canadian with deep-set, sky blue eyes, Dallaire has the thick, callused hands of one brought up in a culture that prizes soldiering, service, and sacrifice. He saw the United Nations as the embodiment of all three.'

Before his posting to Rwanda, Dallaire had served as the commandant of an army brigade that sent peacekeeping battalions to Cambodia and Bosnia, but he had never seen actual combat himself. "I was like a fireman who has never been to a fire, but has dreamed for years about how he would fare when the fire came," Dallaire recalls. When, in the summer of 1993, he received the phone call from UN headquarters offering him the Rwanda posting, he was ecstatic."It's very difficult for somebody not in the service to understand what it means to get a command. He'd sell his mother to do it. I mean, when I got that call, it was answering the aim of my life," he says. "It's what you've been waiting for. It's all you've been waiting for."

Canadian Major General Romeo Dallaire, commander of UN peacekeeping forces in Rwanda.

Dallaire was sent to command a UN force that would help to keep the peace in Rwanda, a nation the size of Vermont, with a population of 8 million, which was known as "the land of a thousand hills." Before Rwanda achieved independence from Belgium in 1962, the Tutsi, who made up 15 percent of the populace, had enjoyed a privileged status. But independence ushered in three decades of Hutu rule, under which Tutsi were systematically discriminated. against and periodically subjected to waves of killing and ethnic cleansing. In 1990 a group of armed exiles, mainly Tutsi, who had been clustered on the Ugandan border, invaded Rwanda. Over the next several years the rebels, known as the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), gained ground against Hutu government forces. In 1993, with the support of the major Western powers, Tanzania brokered peace talks, which resulted in a power-sharing agreement known as the Arusha accords. Under its terms the Rwandan government agreed to govern with Hutu opposition parties and the Tutsi minority. UN peacekeepers would be deployed to patrol a cease-fire and assist in demilitarization and demobilization as well as to help provide a secure environment, so that exiled Tutsi could return.The hope among moderate Rwandans and foreign diplomats was that Hutu andTutsi would at last be able to coexist in harmony.

Hard-line elements within the Rwandan government and Hutu extremists outside it found the Arusha agreement singularly unattractive. They saw themselves as having everything to lose, everything to fear, and nothing obvious to gain by complying with the terms of the peace deal. The Hutu had dominated the Rwandan political and economic scene for three decades, and they were afraid that the Tutsi, who had long been persecuted, would respond in kind if given the chance again to govern.The accord did not grant past killers amnesty for their misdeeds, so those Hutu leaders who had blood on their hands were concerned that integrating Tutsi political and military officials into the government would cost them their freedom or their lives. The Hutu memories of preindependence Rwanda had been passed down through the generations, and Hutu children could recite at length the sins the Tutsi had committed against their forefathers.

Hutu extremists opposed to Arusha set out to terrorize the Tutsi and those who supported power-sharing. Guns, grenades, and machetes began arriving by the planeload." By 1992, Hutu militia had purchased, stockpiled, and begun distributing an estimated eighty-five tons of munitions, as well as 581,000 machetes-one machete for every third adult Hutu male.9 The situation deteriorated dramatically enough in 1993 for a number of international and UN bodies to take interest. In early 1993 Mujawamariya, executive director of the Rwanda Association for the Defense of Human Rights, urged international human rights groups to visit her country in the hopes of deterring further violence. Des Forges of Human Rights Watch was one of twelve people from eight countries who composed the International Commission of Investigation. The commission spent three weeks in Rwanda, interviewing hundreds of Rwandans. The crimes that were being described even then were so savage as to defy belief. In one instance the investigators met a woman who said that her sons had been murdered by Hutu extremists and buried in the mayor's back garden. When the authorities denied the woman's claims, the team knew they had to obtain concrete proof. They descended upon the mayor's doorstep, demanding they be allowed to dig up his garden; the mayor nonchalantly agreed on the condition that they reimburse him for the price of the beans that would be uprooted.The investigators, most of whom were lawyers and none of whom had ever dug up a grave (or even done much gardening), began digging. "We dug and dug and dug," remembers Des Forges, "while the mayor sat there and watched us amateurs with a big smirk on his face."

With the sides of the pit on the verge of collapsing inward, the team had found nothing and was prepared to give up. Only the sight of the woman waiting nearby kept them going. "This woman is a mother," Des Forges told her colleagues. "She may get a lot of things wrong, but the one thing she won't get wrong is where her sons are buried." Minutes later the investigators unearthed a foot. More body parts followed.