A Problem From Hell: America and the Age of Genocide (64 page)

Read A Problem From Hell: America and the Age of Genocide Online

Authors: Samantha Power

Tags: #International Security, #International Relations, #Social Science, #Holocaust, #Violence in Society, #20th Century, #Political Freedom & Security, #General, #United States, #Genocide, #Political Science, #History

Some of Dallaire's colleagues speculated that he was reacting emotionally to his experience in Rwanda because the Belgian press and the families of the deceased Belgian soldiers had vilified him. He claims to be reconciled to his decisions." I've been criticized by the Belgians for sending their troops to a'certain death' by directing them to protect Prime Minister Agathe," he notes. "I'll take that heat, but I could not take the heat of having hunkered down and not having tried to give Agathe the chance to call to the nation to avert violence.You couldn't let this thing go by and watch it happen"

His bigger problem is his guilt over the Rwandans.They entrusted their fate to the UN and were murdered: "I failed my mission," he says. "I simply cannot say these deaths are not mine when they happened on my mission. I cannot erase the thousands and thousands of eyes that I see, looking at me, bewildered. I argued, but I didn't convince, so I failed."

In an effort to help Canadians deal with the stress of their military experiences, Dallaire agreed to produce a thirty-minute video, "Witness the Evil." In the video he says it took two years for the experiences to hit him but that eventually he reached a point where he couldn't "keep it in the drawer" any longer:

I became suicilal because ... there was no other solution. I couldn't live with the pain and the sounds and the smell. Sometimes, I wish I'd lost a leg instead of having all those grey cells screwed up. You lose a leg, it's obvious and you've got therapy and all kinds of stuff. You lose your marbles, very, very difficult to explain, very difficult to gain that support that you need.''

As the passage of time distanced Dallaire from Rwanda, the nights brought him closer to his inner agony. He carried a machete around and lectured cadets on post-traumatic stress disorder, he slept sparingly, and he found himself nearly retching in the supermarket, transported back to Rwandan markets and the bodies strewn within them. In October 1998 Canada's chief of defense staff, General Maurice Baril, asked Dallaire to take a month of stress-related leave. Dallaire was shattered. After hanging up the phone, he says,"I cried for days and days" He tried to keep up a brave public front, sending a parting e-mail to his subordinates that read: "It has been assessed essential that I recharge my batteries due to a number of factors, not the least being the impact of my operational experience on my health.... Don't withdraw, don't surrender, don't give up."""

Dallaire returned from leave, but in December 1999 Baril called again. He had spoken with Dallaire's doctors and decided to force a change with an ultimatum: Either Dallaire had to abandon the "Rwanda business" and stop testifying at the tribunal and publicly faulting the international community for not doing more, or he would have to leave his beloved armed forces. For Dallaire, only one answer was possible: "I told them I would never give up Rwanda," he says. "I was the force commander and I would complete my duty, testifying and doing whatever it takes to bring these guys to justice." In April 2000 Dallaire was forced out of the Canadian armed services and given a medical discharge.

llallaire had always said, "The day I take my uniform off will be the day that I will also respond to my soul." But since becoming a civilian he has realized that his soil is not readily retrievable. "My soul is in Rwanda," he says. "It has never, ever cone back, and I'm not sure it ever will." He feels that the eyes and the spirits of those killed continue to watch him.

In June 2000 a brief Canadian news wire story reported that Dallaire had been found unconscious on a park bench in Hull, Quebec, drunk and alone. He had consumed a bottle of scotch on top of his daily dose of pills for posttraumatic stress disorder. He was on another suicide mission. After recovering, Dallaire sent a letter to the Canadian Broadcast Corporation thanking them for their sensitive coverage of this episode. His letter was read on the air:

Thank you for the very kind thoughts and wishes.

There are times when the best medication and therapist simply can't help a soldier suffering from this new generation of peacekeeping injury. The anger, the rage, the hurt, and the cold loneliness that separates you from your family, friends, and society's normal daily routine are so powerful that the option of destroying yourself is both real and attractive. That is what happened last Monday night. It appears, it grows, it invades, and it overpowers you.

In my current state of therapy, which continues to show very positive results, control mechanisms have not yet matured to always be on top of this battle. My doctors and I are still [working to] establish the level of serenity and productivity that I yearn so much for. The therapists agree that the battle I waged that night was a solid example of the human trying to come out from behind the military leader's ethos of"My mission first, my personnel, then myself." Obviously the venue I used last Monday night left a lot to be desired and will be the subject of a lot of work over the next while.

Dallaire remained a true believer in Canada, in peacekeeping, in human rights.The letter went on:

This nation, without any hesitation nor doubt, is capable and even expected by the less fortunate of this globe to lead the developed countries beyond self-interest, strategic advantages, and isolationism, and raise their sights to the realm of the pre-eminence of humanism and freedom ....Where humanitarianism is being destroyed and the innocent are being literally trampled into the ground ... the soldiers, sailors, and airpersons ... supported by fellow countrymen who recognize the cost in human sacrifice and in resources will forge in concert with our politicians ... a most unique and exemplary place for Canada in the league of nations, united under the United Nations Charter.

I hope this is okay.

Thanks for the opportunity.

Warmest regards,

Dallaire

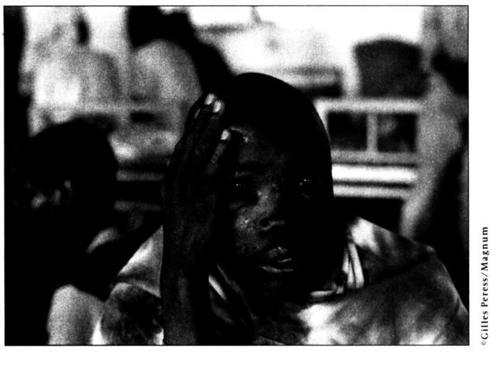

A defaced photograph of a Muslim family found when they returned to their home after the Dayton agreement. The Serbs had looted the family's furniture, appliances, cabinets, sinks, and window panes. The photo was virtually all that remained.

Chapter 11

Srebrenica:

"Getting Creamed"

On July 11, 1995, a year afterTutsi rebels finally halted the Rwandan genocide and a full three years into the Bosnian war, Bosnian Serb forces did what few thought they would dare to do. They overran weak UN defenses and seized the safe area of Srebrenica, which was home to 40,000 Muslim men, women, and children.

The Srebrenica enclave had been declared "safe" back in the spring of 1993, just after the Clinton administration abandoned its proposal to lift the arms embargo against the Muslims and bomb the Serbs. Srebrenica was one of six heavily populated patches of Muslim territory that the UN Security Council had sent lightly armed peacekeepers to protect.

The UN had hoped that enough peackeepers would be deployed to deter Serb attacks, but President Clinton had made it clear that the United States would not send troops, and the European countries that had already deployed soldiers to Bosnia were reluctant to contribute many more peacekeepers to a failing UN effort. Those blue helmets that did deploy had a tough time. Sensing a Western squeamishness about casualties after Somalia and Rwanda, outlying Serb forces frequently aimed their sniper rifles at the UN soldiers. They also repeatedly choked off UN fuel and food. By the time of the July attack on Srebrenica, the 600 Dutch peacekeepers were performing most of their tasks on mules and were living off emergency rations. So few in number, they knew that if the Bosnian Serbs ever seriously attacked, they would need help from NATO planes in the sky. In 1994 the Western powers had established a process by which UN peacekeepers in Bosnia could appeal for "close air support" if they themselves came under fire, and they could request air strikes against preselected targets if the Muslim-populated safe areas came under serious attack. In a cumbersome command-and-control arrangement meant to limit the risk to peacekeepers, the NATO foreign ministers agreed that "dual keys" had to be turned before NATO jets would be sent to assist UN troops in Bosnia. The civilian head of the UN mission, Yasushi Akashi, had to turn the first key. If this happened, then NATO commanders would need to turn the second. Most requests were stalled at the initial stage, as UN civilians were openly skeptical of NATO bombing. They believed it would destabilize the peace process and cause the Serbs to round up UN hostages, as they had done in November 1994 and May 1995.

When the Serbs called the international community's bluff ill July 1995, their assault went virtually uncontested by the United Nations on the ground and by NATO jets in the sky. At 4:30 p.m. on July 11, the ruddyfaced, stout commander of the Bosnian Serb army, Ratko Mladic, strolled into Srebrenica. General Radislav Krstic, the chief of staff of the Drina corps, which had executed the attack, accompanied him. Krstic had lost his leg the year before when he ran over a mine planted by Muslim forces. So the victory was particularly sweet. With Krstic standing nearby, Mladic announced on Bosnian Serb television, "Finally, after the rebellion of the Dahijas, the time has come to take revenge on the [Muslims] in this region."'

Over the course of the following week, Mladic separated the Muslim men and boys of Srebrenica from the women. He sent his forces in pursuit of those Muslims who attempted to flee into the hills. And all told, he slaughtered some 7,000 Muslims, the largest massacre in Europe in fifty years. The U.S. response, though condensed in time, followed the familiar pattern. Ahead of and during the Serb assault, American policymakers (like Bosnian civilians) again revealed their propensity for wishful thinking. Once the safe area had fallen, U.S. officials narrowly defined the land of the possible. They placed an undue faith in diplomacy and reason and adopted measures better suited to the "last war." But a major difference between Srebrenica and previous genocides in the twentieth century was that the massacres strengthened the lobby for intervention and the understanding, already ripening within the Clinton administration, that the U.S. policy of nonconfrontation had become politically untenable. Thus, in the aftermath of the gravest single act of genocide in the Bosnian war, thanks to America's belated leadership, NATO jets engaged in a three-week bombing campaign against the Bosnian Serbs that contributed mightily to ending the war.

Warning

"The Sitting-Duck Position"

Diplomats, journalists, peacekeepers, and Bosnian Muslims had lived for a long time with the possibility that the Serbs would seize the vulnerable safe areas of eastern Bosnia. The enclaves were so unviable that U.S. intelligence analysts placed bets on how long they would survive. Richard Holbrooke had finally become involved in shaping America's Bosnia policy in September 1994 when he was appointed assistant secretary of state for European and Canadian affairs. He says he told the queen of the Netherlands that Dutch troops in Srebrenica were in the "Dien Bien Phu of Europe" facing a "catastrophe waiting to happen"

In June 1995 the UN force commander Bernard Janvier had unveiled a proposal at the Security Council to withdraw the blue helmets from the three eastern enclaves. He argued that peacekeepers were too lightly armed and few in number to protect Muslim civilians. U.S. ambassador Albright, a strong defender of what was left of Bosnia, exploded. She said Janvier's plan to "dump the safe areas" was "flatly and completely wrong." Albright had lost countless battles at the National Security Council to convince the president to order the bombing of the Serbs. Now, though she was rejecting Janvier's proposal as inhumane, she knew she could offer no suggestions as to how either the Muslim civilians or the lightly armed peacekeepers would survive in the face of Serb attack.The reality, obvious to all, was that the safe areas would be safe only as long as the Serbs chose to leave them so.

Many western policymakers secretly wished Srebrenica and the two other Muslim safe areas in eastern Bosnia would disappear. By the summer of 1995, both the Bosnian Serbs and the Muslim-led government were exhausted, and western negotiators thought they were closer than ever to reaching a settlement. But because the three eastern enclaves did not abut other Muslim-held territory, they were a recurrent sticking point in negoti- ations.The international community could not very well ask the Muslims, the war's main victims, to leave the enclaves voluntarily, especially since most of the Muslims inhabiting them had already been expelled from their homes in neighboring villages. The Muslim government would be lambasted by its own citizens if it handed over to the Serbs any of the few towns still in Muslim hands. And the Serb nationalists were not about to agree to a peace deal that preserved Muslim enclaves, which tied down Serb troops and kept nettlesome Muslims in their midst. The whole idea behind Republika Srpska had been the creation of an ethnically pure Serb state.