A Quiet Vendetta (3 page)

Authors: R.J. Ellory

‘Well, whoever the hell did this, he left the heart inside the chest.’

‘Seems to me we go with the car,’ Verlaine said. ‘The car is good, strong. Maybe it’s a red herring, something so out of character it’s designed to throw the whole pitch of the invest, but it’s such a big part I somehow doubt it. Someone wants to throw the course they do something small, something at the scene, some minor fact that’s so minor only an expert would recognize it. The guys who do that kind of thing are smart enough to realize that the people after them are just as smart as they are.’

Emerson nodded. ‘You go down to the coroner’s office and take a look yourself. I’ll get this typed up and file it.’

Verlaine rose from the chair. He set it back against the wall.

He shook Emerson’s hand and turned to leave.

‘Keep me posted on this,’ Emerson said as an afterthought.

Verlaine turned back, nodded. ‘I’ll send you an e-mail.’

‘Wiseass.’

Verlaine pushed through the door and made his way down the corridor.

Heat had risen outside. Sweated on the way to his car, maybe a pint a yard.

County Coroner Michael Cipliano, fifty-three years old, an irascible and weatherworn veteran. Now only Italian by name, his father from the north, Piacenze, Cremona perhaps – even he’d forgotten. Cipliano’s eyes were like small black coals burning out of the smooth surface of his face. Gave no shit, expected none in return.

The humid, tight atmosphere that clung to the walls of the coroner’s theater defied the air-conditioning and pressed relentlessly in from all sides. Verlaine stepped through the rubber swing doors and nodded silently at Cipliano. Cipliano nodded back. He was hosing down slabs, the sound of the water hitting the metal surface of the autopsy tables almost deafening within the confines of the theater.

Cipliano finished the last table nearest the wall and shut off the hose.

‘You here for the heartless one?’

Verlaine nodded again.

‘Printed him for you I did, like the blessed patron saint that I am. Paper’s over there.’ He nodded at a stainless steel desk towards the back of the room. ‘Gopher’s sick. Took off day before yesterday, figured he picked something up from one of those John Does over there.’ Cipliano nodded over his shoulder to a pair of cadavers, floaters from all visible indications, the grey-blue tinge of the flesh, the swollen fingers and toes.

‘Found ’em Thursday face down in Bayou Bienvenue. Users both of them, tracks like pepper up and down their arms, in the groin, between the toes, backs of the knees. Gopher figures there’s cholera or somesuch in the Bayou. These cats roll in here with it and he contracts. Full of shit, really so full of shit.’

Cipliano laughed hoarsely and shook his head.

‘So what we got?’ Verlaine asked as he walked towards the nearest table. The smell was strong, rank and fetid, and even though he breathed through his mouth he could almost taste it. God only knew what he was inhaling.

‘What we got is a fucking mess and then some,’ Cipliano said. ‘If my mother only knew where I was on a Sunday morning she’d roll over Beethoven right there in her grave.’ The lack of reciprocal love between Cipliano and his five-years-dead mother was legend to anyone who knew him. Rumor had it that Cipliano had performed her autopsy himself, just to make sure, to make

really

sure, that she was dead.

‘Aperitifs and hors d’oeuvres are done, but at least you arrived in time for the main course,’ Cipliano stated. ‘Whoever did your John Doe here knew a little something about surgery. It ain’t easy to do that, take the heart right out clean like that. It wasn’t no pro job, but there’s one helluva lot of veins and arteries connecting that organ, and some of them are the thickness of your thumb. Messy shit, and really quite unusual if I say so myself.’

The skin of the corpse was gray, the face distorted and swollen with the heat it must have suffered locked in the trunk of the car. The chest revealed the incisions Cipliano had already made, the hollowness within that had once held the heart. The stomach was bloated, the heap of clothes bloodstained, hair like clumps of matted grass.

‘A clean-edged knife,’ Cipliano stated. ‘Something like a straight razor but without the flat end, here and here through the left and right ventricles at the base, and here . . . here across the carotid we have a little chafing, a little friction burn where the blade did not immediately pass through the tissue. Subclavian incisions and dissections are clean and straight, swift cuts, quite precise. Perhaps a scalpel was used, or something fashioned to the accuracy of a scalpel.’

‘Was the whole thing done in one go, or was there time between opening up the chest and severing the heart?’ Verlaine asked.

‘All in one go. Tied him up, beat his head in, opened him up like a jiffy bag, severed some of the organs to get to the heart. The heart was cut out, replaced inside the chest. The vic was already lying on the sheet, it was wrapped over him, dumped in the car, driven from wherever, and transferred to the trunk, abandoned.’

‘Lickety-split,’ Verlaine said.

‘Like the proverbial hare,’ Cipliano replied.

‘How long would something like that take, the whole operation thing?’

‘Depends. From his accuracy, the fact it was obvious he had some idea of what he was doing, maybe twenty minutes, thirty at best.’

Verlaine nodded.

‘Seems the body was moved, tilted upwards a couple of times, maybe even propped against something. Blood has laked in different places. Struck with the hammer maybe thirty or forty times, some of the blows direct, others glancing towards the front of the head. Tied initially, and once he was dead he was untied.’

‘Fingerprints on the body?’ Verlaine asked.

‘Need to do an iodine gun and silver transfers to be sure, but from what I can tell there seem to be plenty of rubber smudges. He wore surgical gloves, I’m pretty sure of that.’

‘Can we do helium-cadmium?’

Cipliano nodded. ‘Sure we can.’

Verlaine helped prepare. They scanned the limbs, pressure points, around each incision, the gray-purple flesh a dull black beneath the ambient light. The smears from the gloves showed up as glowing smudges similar to perspiration stains. Where the knife had scratched the surface of the skin there were fine black needle-point streaks. Verlaine helped to roll the body onto its front, a folded body bag tucked into the chest cavity to limit spillage. The back showed nothing of significance, but Verlaine – bringing his line of vision down horizontally with the surface of the skin – noticed some fine and slightly lustrous smears on the skin.

‘Ultra-violet?’ he asked.

Cipliano wheeled a standard across the linoleum floor, plugged it in and switched it on.

The coal black eyes squinted hard. ‘Shee-it and Jesus Christ in a gunny sack,’ he hissed.

Verlaine reached towards the skin, perhaps to touch, to sense what was there. Cipliano’s hand closed firmly around his wrist and restrained the motion.

A pattern, a series of joined lines glowing whitish-blue against the colorless skin, drawn carefully from shoulder to shoulder, down the spine, beneath the neck and over the shoulders. It glowed, really glowed, like something alive, something that possessed an energy all its own.

‘What the fuck is that for Christ’s sake?’ Verlaine asked.

‘Get the camera,’ Cipliano said quietly, as if here he had found something that he did not wish to disturb with the sound of his voice.

Verlaine nodded, fetched the camera from the rack of shelves at the back of the room. Cipliano took a chair, placed it beside the table and stood on it. He angled the camera horizontally as best he could and took several photographs of the body. He came down from the chair and took several more shots across the shoulders and the spine.

‘Can we test it?’ Verlaine asked once he was done.

‘It’s fading,’ Cipliano said quietly, and with that he took several items from a field kit, swabs and analysis strips, and then with a scalpel he removed a hair’s-width layer of skin from the upper right shoulder and placed it between two microscope slides.

Less than fifteen minutes, Cipliano turning with a half-smile tugging at the corners of his mouth. ‘Formula C

2

H

24

N

2

O

2

. Quinine, or quinine sulphate to be precise. Fluoresces under ultraviolet, glows whitish-blue. Only other things I know of that do that are petroleum jelly smeared on paper and some kinds of detergent powder. But this, this is most definitely quinine.’

‘Like for malaria, right?’ Verlaine asked.

‘That’s the shit. Much of it’s been replaced with chloroquinine, other synthetics. Take too much and it gives you something called cinchoism, makes your ears ring, blurs your vision, stuff like that. Lot of guys from out of Korea and ’Nam took the stuff. Most times comes in bright yellow tablets, can come in a solution of quinine sulphate which is what we have here. Used sometimes as a febrifuge—’

‘A what?’

‘Febrifuge, something to knock out a fever.’ Verlaine shook his head. His eyes were fixed on the faint lines drawn across the dead man’s back. Glowed like St Elmo’s fire, the

ignis fatuus

that hung across the swamps and everglades, mist reflecting light in every shattered molecule of water. The effect was disquieting, unnatural.

‘I’ll get the pictures processed. We’ll have more of an idea of what the configuration means.’

That word – configuration – stuck in Verlaine’s thoughts for as long as he remained at the County Coroner’s office, sometime beyond that if truth be known.

Verlaine watched as Cipliano picked the body to pieces, searching for grains, threads, hairs, taking samples of dried blood from each injured area. There were two types, the vic’s A positive, the other presumably the killer’s, AB negative.

The hairs belonged to the dead guy, no others present, and scraping beneath the fingernails Cipliano found the same two types of blood, a skin sample that proved too decayed to be tested effectively, and a grain of burgundy paint that matched the car.

Verlaine left then, took with him the print transfers Cipliano had made, asked him to call when the pictures were processed. Cipliano bade him farewell and Verlaine passed out through the swing doors into the brightly-lit corridor.

Outside the air was thick and tainted with the promise of storm, the sun hunkered down behind brooding clouds. The heat breathed through everything, turned the surface of the hot top to molasses, and Verlaine stopped to buy a bottle of mineral water from a store on the way back to his car.

There was something present today, something in the atmosphere, and breathing it he felt invaded, even perhaps abused. He sat in his car for a while and smoked a cigarette. He decided to drive back to the Precinct House and wait there for Cipliano’s call.

The call came within an hour of his arrival. He left quickly, as inconspicuously as he could, and drove back across town to the coroner’s office.

‘Have a make on the pattern,’ Cipliano stated as Verlaine once again entered the autopsy theater.

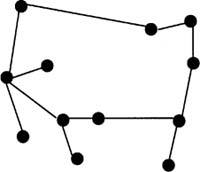

‘It appears to be a solar configuration, a constellation, a little crude but it’s the only thing the computer can get a fix on. It matches well enough, and from the angle it was drawn it would be very close to what you’d see during the winter months from this end of the country. Maybe that holds some significance for you . . .’

Cipliano indicated the computer screen to his right and Verlaine walked towards it.

‘The constellation is called Gemini, but this pattern contains all twelve major and minor stars. Gemini is the two-faced sign, the twins. Mean anything to you?’

Verlaine shook his head. He stared at the pattern presented on the screen.

‘So, you get anything on the prints?’ Cipliano asked.

‘Haven’t put them through the system yet.’

‘You can do that today?’

‘Sure I can.’

‘You got me all interested in this one,’ Cipliano said. ‘Let me know what you find, okay?’

Verlaine nodded, walked back the way he’d come, drove across once more to the crime scene at the end of Gravier.

The alleyway was silent and thick with shadows, somehow cool. As he moved, those self-same shadows appeared to move with him, turning their shadow-faces, their shadow-eyes towards him. He felt isolated, and yet somehow not alone.

He stood where the Mercury had been parked, where the killer had pulled into the bay, turned the engine off, heard the cooling clicks of the motor; where he’d perhaps smiled, exhaled, maybe paused to smoke a cigarette before he left. Job done.

Verlaine shuddered and, stepping away from the sidewalk, he moved slowly to the wall that only days before had guarded the side of the Cruiser from view.

He left quickly. It was close to noon. Sunday, the best day perhaps to find a space in the schedule to get the prints checked against the database. Verlaine figured to leave the transfers with Criminalistics and go check out the Cruiser at the pound. He logged the request, left the transfers in an envelope at the desk, scribbled a note for the duty sergeant and left it pinned to his office door just in case they came looking for him.