A Rainbow of Blood: The Union in Peril an Alternate History (17 page)

Read A Rainbow of Blood: The Union in Peril an Alternate History Online

Authors: Peter G. Tsouras

Tags: #(¯`'•.¸//(*_*)\\¸.•'´¯)

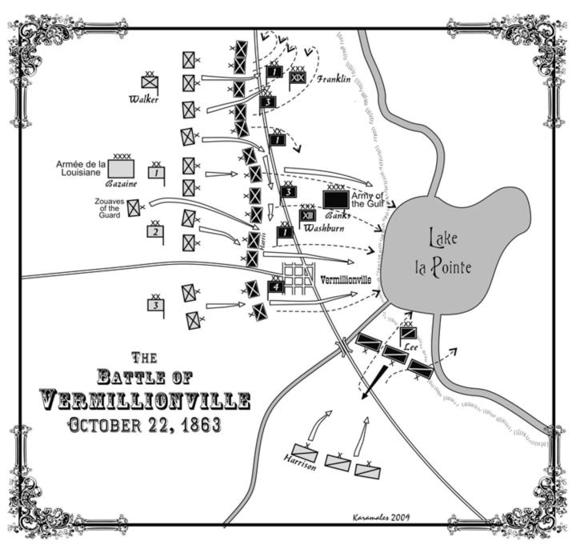

VERMILLIONVILLE, LOUISIANA, 2:22 PM, OCTOBER 21, 1863

Banks never knew what hit him that afternoon. Bazaine's attack crashed

into his army all along the line. The French general had reduced his tactical problem to a very simple point-it would be a shoving match with all

the odds on his side. Banks could shove him westward all he wanted; the

ground stretched easily and unimpeded for mile after empty mile. He

would simply be falling back on his communications. However, Bazaine

had only to shove Banks's corps east for a tenth of a mile before they

were pushed into Lake La Pointe or fell off a short, steep plateau into the

shallow river that fed into the lake at its base. Should they struggle out of

that, their retreat east would carry them into the marshy waters of Bayou

Teche, and beyond that Lake Grand. A very simple problem indeed.

Banks's army was positioned in line of battle on a north-south axis

just east of the main road leading north from Vermillionville. Major General Franklin's XIX Corps was on the right flank, with XIII Corps on the

left and the cavalry held in reserve.

Banks may have been an amateur who rejected Franklin's sound advice, but his two corps were veterans, and Bazaine's army felt their bite

immediately. But they were victims of a saying by Alexander the Great's

canny father, Phillip II-an army of deer commanded by a lion will always beat an army of lions commanded by a deer. They also suffered

from the damned had luck of fighting an army of lions commanded by

a lion. Banks almost immediately proved the long-dead Macedonian

correct by losing control of the battle. He forgot, if he had ever learned,

that the primary role of the commander in battle is the allocation of the

reserve. So, when Washburn tried to relieve the quickly depleted brigade on the right of his corps, Banks countermanded the order for the replacement brigade to move into the line. However, Banks never countermanded Washburn's original order for the brigade in contact to pull out.

The Prince de Polignac saw the confusion in the opposing firing line

as it filed away to the rear, leaving a gaping hole. He rode to the front of

his two regiments, pointed his sword to the void in the enemy line, and

shouted, "En avant, mes enfants!" and in English, "Go, get'em, boys!" The

Texans responded with high-keening Rebel yells, borrowed in admiration from their mortal Comanche enemies on the wild frontier. At the

sound, the neighboring French Zouaves instinctively paused in their

firing; it was savage and alien to their military style and experience. The

Yankees were all too familiar with it.

The Texans raced through the opening. Franklin was not even

aware of what was going on. He had all he could do trading hammers

and blows with Walker's Greyhounds. His men were Grant's veterans

of the Vicksburg Campaign, but they had never seen such hard fighting.

It was Franklin's great good luck that Polignac rolled up the flank of XIII

Corps instead of turning north against his own corps. Struck from flank

and rear, Washburn's brigades came apart. The prince was riding the

foaming crest of a tidal wave, his colors party desperately trying to keep

up with him. His Texans, exultant in their success, followed the gallant

chevalier of France as his ancestors had followed the plume of Henry IV.

There was no doubt that they were led by a fighting man who met every

standard of Texican manhood.

So when they saw him lurch back in the saddle, his sword flying

from his hand, a groan rose from their ranks. His aide was beside him

in an instant to prevent him from falling from his horse. Men rushed up

on foot to ease him to the ground. His regiments rushed by, stabbing

with their bayonets and bludgeoning the fleeing mass of panicked men

in blue. Bazaine watched in awe. He thought he had seen everything. He

said to his staff, "You see, messieurs, the furor Texicus. Consider it your

privilege to have witnessed it." He paused only for the briefest moment,

then announced. "Now I shall commit my reserve." He called forward

the commander of the Imperial Guard Zouave regiment and pointed

farther down the Union line that was now showing the effects of the disaster rolling up their flank. "There, Colonel Moreau, there is where you

will strike, and they will fly apart."

On the open southern flank of the battle, the two great cavalry hosts

faced each other. Bazaine had placed his cavalry there to tell the enemy

plainly that his line of communications had been cut. That does wonders

for an enemy's confidence, he knew, and it had done just that, sending

excited shouts through the XIII Corps regiments along the line as the

French were advancing rapidly on them from their front. Banks had been

provoked to bring his cavalry division of almost three thousand men

out of reserve. He gave Brig. Gen. Albert Lee the order to drive the enemy cavalry from the field. Lee would have suggested, had Banks been

anything but visibly panicked, that he now deal with the French cavalry

as dismounted infantry employing their Sharps breechloading carbines to bring down so many that they would have to move off. Instead, he

found himself drawing his saber and riding to the head of his thirteen

regiments.

Across the field, the French commander also drew his saber as his

Chasseurs a Cheval, hussars, and lancers sat stock still waiting for the

command. The French would have been outnumbered had the cavalry

of Harrison's brigade not reinforced them. The Texans were not used

to the massed cavalry action that clearly was shaping up, but they were

game for anything. While the French thought in terms of their sabers and

lances, the Texans felt the handles of their revolvers.

From across the field, the French and Texans heard the Union

bugle call signaling the advance at a trot. The entire Union division was

quickly in motion. The French commander waited to let his horses save

their strength for the last command when they would burst forward in a

gallop. Let the Americans tire their horses. He would wait. After all, he

was a veteran of a dozen European and North African battlefields, and

he knew cavalry. When the Americans had closed half the distance between them, he gave his own order and the serried, colorful French lines

flowed forward, the drabber Texans on their right flank. At the last moment, the French bugle call for the charge at the gallop sounded, and the

French squadrons seemed to leap forward as sabers and lances dropped

to the attack. The French were in their element, their national spirit embodied in the wild assault of mounted chivalry, the white arm of the

French Army. A shout of "Urraaaah!" ripped from them seconds before

five thousand horsemen crashed into each other.

In the center, Washburn was overwhelmed by the unfolding disaster, swept away by the flood of fugitives from his disintegrating front.

It was then that the Zouave Regiment of the Guard swept forward in a

blaze of color-big, bearded men advancing in impeccable order until

Moreau bellowed across their front, "En avant, mes enfants! En avant!"

With a shout, they charged. Behind them, Bazaine ordered a general

advance. Moreau led his Zouaves against that part of the line held by the

Iowa and Wisconsin regiments of one of Washburn's stoutest brigades,

commanded by Col. Charles L. Harris, the last steady unit as the rest

wavered.

The farmers of the 11th Wisconsin were veterans to the core, hammered into a special toughness under Grant in the Vicksburg Campaign, the same mettle as the three Iowa regiments in line with them. Their

front was already littered with the fallen, but they responded with precision to the command to fire. A sheet of flame spit from the line, and the

charging Zouaves went down by the hundreds. Their entire colors party

was swept away as the eagle fell to the ground. Miraculously, Moreau

was untouched, despite riding at the head of his regiment. He would

find eight bullet holes in his uniform and cap that night. He looked back

to see a guardsmen snatch up the fallen colors and rush forward. The

impetus of the charge had not been broken as his Zouaves jumped over

the bodies of the dead and wounded. Still, they dropped as the Americans were firing at will. The eagle went down again, and again it was

retrieved to lead the crest of the attack, and for a third time it fell and

rose again. Moreau found himself rolling in the dirt, his horse dead, and

himself bleeding from wound in the thigh. He staggered to his feet and

faced forward.

Bazaine's staff was exclaiming their admiration for the charge of the

Guard Zouaves, but their general saw the American line stiffening by the

example of Harris's brigade. "Messieurs, it will not do for the Emperor's

Guards to not have their glory. Let us help them." By then, the Zouaves

had fallen hack a hundred yards, dragging their colonel and colors with

them. French artillery rolled up on either flank to pour canister into the

Wisconsin and Iowa men. They might have stood all day had not the

panic on their right finally dissolved their flank brigade as the Prince de

Polignac's Texans hammered their way down the line. Harris tried to

refuse his right, but the 21st Iowa was swept away by the flood of fugitives. It was then that Moreau, a bandage around his thigh and mounted

on a fresh horse, again ordered the pas de charge. The drums beat above

the din of battle. Again the Zouaves came on in a rush, and again many

fell, but the American fire slackened and then died away as the brigade

fell back.

With that, the entire XIII Corps ceased to be a fighting formation,

save for the remnant of Harris's brigade, and turned into a mass of fleeing men and vehicles. They did not see the drop of the plateau until

it was too late, and the men behind pushed over hundreds of those in

front. Caissons, guns, wagons, and ambulances careened over the edge

to shatter at the base in a mass of splintered wood and maimed screaming horses. The thousands on foot tumbled over the precipice to leap into the shallow, marshy water of the bayou that fed into Lake La Pointe.

Many more fell into the lake itself to drown splashed helplessly about.

Into this chaos, the remnants of Banks's cavalry were slowly pushed

toward the lake from the south. The cavalry fight had been the most vicious of all the killing that day, for it was man-to-man fighting at sword

or lance length, and a pistol was just as close in that mass of struggling

men and animals. Superior French skill with saber and lance were

matched with American practice with the revolver, but the unraveling

of XIII Corps forced Lee to save what he could. Only parts of the 1st

Louisiana (Union loyalists), 2nd Illinois, and 4th Indiana were able to cut

their way out of the French encirclement. The rest were driven into the

shallows of the lake to add the terror of animals and shouts of men to the

miasma hanging over the battlefield.

Thousands were already surrendering. Only the survivors of Harris's Brigade kept any semblance of order as they fought backward,

leaving their dead and wounded in their trail. By the time they had been

pressed to the edge of the plateau, Harris realized they could go no farther. He ordered his men to throw down their weapons. Moreau rode up

to him, the side of his horse soaked with the blood that oozed from his

thigh, and saluted with his sword as Harris offered his. Moreau refused

and said in French that he could not accept the sword of such a gallant foe. Harris didn't understand a word, but the sentiment was plain

enough. He was glad of what little balm he could find.

Bazaine rode into the chaos that has long ceased being a battle as his

troops were disarming the dazed Americans. Banks, most dazed of all,

was led up to him by the Chasseurs a Pied that had captured him. In that

effusion of gracious condescension at which the French excel, he greeted

Banks, complimented him on his conduct of the battle, ascribed the

fate of the battle to Dame Fortune, and invited him to share his dinner

that night.

Barely two hundred yards from this exquisite chivalry, the Sudanese had lost all sense of restraint. They had fought through the toughest

part of the battle carried forward in the last charge by the intoxication

of their battle cry, "Allah u akbar!" They just found it easier to kill when

men threw down their weapons. Possessed already of the African Muslim style of war, they were like beasts. Their French officers had done nothing to restrain them against the Mexicans and now could do nothing

with them.