A Rainbow of Blood: The Union in Peril an Alternate History (34 page)

Read A Rainbow of Blood: The Union in Peril an Alternate History Online

Authors: Peter G. Tsouras

Tags: #(¯`'•.¸//(*_*)\\¸.•'´¯)

Greyhound leading the first division, true to her name, dashed ahead

and passed the fort without notice. Peterel was next, followed by Desperate. Each had followed the running lights of the ship ahead. They were

clean through when the garrison's guns came to life. The diversion at the

gate had worked well enough to draw most of the garrison out of their

beds to defend the gate, leaving only a few guards to peer down at the

broad expanse of the water. The moon had already set the night before,

and the only illumination came faintly from the stars. The dawn would

he creeping over the wood line to the east, its first faint light more confusing to the eye than night itself. Dunlop had factored this into his plan if they should be late. But chance had given him all her favors when the

first division got clean through. The guards had seen the sparks from the

ships' funnels, sounded the alarm, and thrown torches into the piles of

wood along the shore. The garrison had rushed to the guns. The gunners

did not fire wildly into the darkness but adjusted their pieces to the plots

of their preset range tables for ships passing below through the main

ship channel.

Chance now played against the British and confused the lead pilot of the second division, doubly unnerved by the guns firing down at

them. He directed Racer too far west and ran her into the shallow river

mud. Taking her lead, Icarus followed to stick herself fast as well. Just in

time, Spiteful's captain turned her back into the main channel, signaling

frantically to the following gunvessel division to follow her closely.

The darkness still held off the approaching half light. The garrison had long practiced on well-drawn firing tables that raked the river

approaches to the fort and the main channel beneath it. Spiteful took two

hits as she steamed past. The gunvesssel Steady was hit repeatedly and

began to settle. The other two gunvessels pushed past her and out of

the range of the fort's guns. With most of the enemy flotilla safely run

past their guns, the gunners of Fort Washington took special pleasure

in turning the stranded Racer and Icarus into matchwood as the dawn

revealed them. The shells started fires amid the wreckage, and soon two

ship's funeral pyres were sending their smoke into the morning air.'

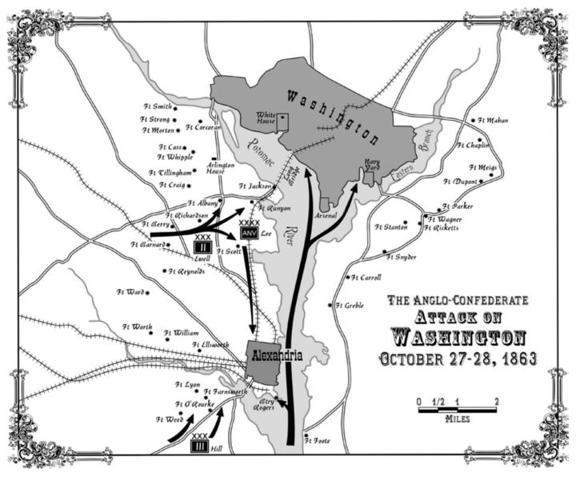

LAYFAYETTE SQUARE, 5:40 AM, OCTOBER 28, 1863

Sharpe took the patrol leader's report himself. Despite the uproar on

the other side of the Potomac, he listened intently when Hooker's Horse

Marines brought him news of the joint forces of a Confederate brigade

and a British flotilla just sixteen miles below Washington. The sergeant

finished his report, "We barely got back through our lines just south of

Alexandria and on the road to the Long Bridge when the Rebs broke

through from the west, sir."

"Good report. Now let's talk to the prisoner."

The sailor, who had been in the background, perked right up. "It's

a deserter I am, your lordship, strictly speaking. I said to myself, Richard

Foley, 'Foley, it's about time you absolved yourself of allegiance to Her Majesty and quit her service.' And every fourth man in the Royal Navy

an Irishman, and a great shame it is with England's boot on poor Ireland's throat. That's just what I did, your lordship, deserted from Nettle,

I did. Now, I says to myself, 'Foley, it's time to became an American like

so many of your kin.' And, so, you see, your lordship, it's both a deserter

and recruit I am and not a prisoner."

Sharpe would have enjoyed this conversation if the whole world

did not seem to have started crashing down, "There's only room in this

conversation for one lawyer, Foley, and it is not you. If you have any

hope of becoming an American and not being turned over to the British

after this war is over, you will tell me what you know of the strength and

purpose of these ships."

That threat cut right through the blarney, and Sharpe discovered

that he had before him an observant and shrewd man. The room had

grown silent as Foley listed the ships and the flotilla's mission and the

particular mission of his own vessel to escort the Confederate infantry,

ending with, "And I heard the officers say they would love to watch the

White House burn just as their grandfathers had."

The telegraph clattered with the alarm to the War Department and

the headquarters of Major General Augur, commander of the Washington defenses. Sharpe sent his cavalry sergeant with the warning dashing

to the Navy Yard. He saw the man's horse strike sparks on the cobbles

as he himself ran across Lafayette Park to the White House. He found

Lincoln walking down the graveled driveway with his new bodyguard

following. He gave the man a hard look, and the man returned it, bold

and angry. He was relieved to see Major Tappen and a squad walking

just behind.

"Mr. President, I'm glad I found you. I must speak with you."

"Sharpe, when I see a general sprinting toward me, I take it he has

something to say I should listen to."

"Alone, out of earshot, sir." The bodyguard tried to follow, but a

look from Sharpe stopped him. "Sir, you've heard the guns across the

river. The Rebels have broken through the fort barrier. I do not know

how seriously, but they have cut off the Long Bridge. A British flotilla is

coming up the river, and as we speak probably is trying to fight its way

past Fort Washington. They are escorting a train of barges filled with

Rebel infantry, which my scouts estimate to be a brigade. If they get past the forts, this city will be at their mercy. For that reason, Mr. President,

you must be prepared to leave the city. My men will escort you."

Lincoln paused and looked over Sharpe's shoulder. "You know,

Sharpe, every day when I come to visit you, I pass the statue of Andrew Jackson rearing there on his horse. And I tell him I wish he were

here. You know how much he hated the British and the very thought

of secession." He smiled to himself. "That reminds me of the first time

the hotheads in Charleston talked big of secession in the '30s. Jackson

didn't waffle and let the fuse burn down to this terrible war we have

now like Buchanan.' No, sir. He said that if they so much as tried it, he

would march into South Carolina and hang the first Rebel from the first

tree with the first rope. Well, that shut them up for almost thirty years.

Someday when I met my maker, I would have to explain to Jackson how

I ran away. I can't imagine that he would have. And I can't imagine that I

would let the old general down." He put his hand on Sharpe's shoulder.

"The president of the United States will not abandon the capital of the

Union."

He let the gravity of what he had said sink in. "Now, Sharpe, let's

see what else we can do to avoid the awful sight of my ugly carcass being run out of town."

ALEXANDRIA, VIRGINIA, 7:10 AM, OCTOBER 28, 1863

Lieutenant General Ewell poured his corps through the hole punched

by the Stonewall Brigade. He turned Maj. Gen. Juhal Early's division

toward the Long Bridge and Maj. Gen. Edward Johnson's toward Alexandria. The sound of fighting drifting south was the signal Hill's corps,

now commanded by Maj. Gen. Richard Anderson, was waiting for; he

launched his corps in another assault on the forts defending Alexandria.

Brig. Gen. George H. Steuart took Johnson's lead brigades south

parallel to the Potomac, ruthlessly driving all civilian refugee traffic off

the road and capturing dozens of wagons supplying the forts from the

vast munitions warehouses across the river in the Washington Arsenal.5

The cost was heavy; artillery from the remaining forts raked his column

of Maryland, North Carolina, and Virginia regiments as he hurried his

men along at the double time. The fiery Marylander was in a hurry. His

orders were to drive through the town and take Battery Rogers to help

the British come up the river and assault Washington. He was finally out of artillery range a mile from the town, but he kept up the pace. Those

who dropped out were the price of getting there on time.

His men pounded into a town that was in complete panic. With

its railroad yard, supply depots, warehouses, and hospitals, it was the

transportation heart of the Union's war effort in the East. Now trains

were pulling out of the yard, their cars packed with refugees and soldiers. Wagon trains sent to empty the warehouses and ambulances to

evacuate the wounded clogged streets fast filling with people. The rumble of guns to the north and south roiled the crowds with fear. Discipline

was breaking down among the rear-echelon troops who had never heard

a shot fired in anger. The quartermaster officer was suddenly confronted

with defending the town-without the combat troops to do it.

Steuart marched his men straight through the chaos, leaving the

follow-on brigades to sort it out. The deep sound of the big coastal and

naval guns at Battery Rogers came from the river. The battery was in

the right place. It sat at the base of the long finger of land called Jones

Point that jutted out into the Potomac, narrowing it sharply. Its guns

could rake anything that came up the river to pass Alexandria. Little

Nettle and Onyx had crossed the wide mouth of Hunting Creek just below Alexandria to take the battery under fire. With their four relatively

small guns, they steamed to within three hundred yards of the battery's

huge 15-inch Rodman and six Parrott rifles to slug it out. Not a few men

on board the ships must have repeated the famous line of the British

grenadier about to receive the volley of the French Guards at Fontenoy

in 1745, "May the Lord make us truly thankful for what we are about

to receive."6 The senior captain knew that he had no chance in such an

exchange, but his primary mission was to engage the battery so that the

rest of the flotilla could steam past and up to Washington. Battery Rogers

was the Royal Navy's last obstacle to putting the Yankee capital under

its guns.

Commodore Dunlop also had expected an expensive fight to get

past the huge armament of Fort Foote, which was a mile south of Battery Rogers on the Maryland side of the river. To his amazement, they

steamed past without taking a shot. He did not know that the huge guns

reported to be at the fort were scheduled to be installed the following

week. As they moved past the silent fort, the fight for Battery Rogers

was in earnest. The ship channel would take his ships straight into that

action. He could see that Onyx was already going down by the head, its

bronze propeller glistening in the morning light as it was raised in the

air. He did not think Nettle could last long enough to give him time to

steam past.

Steuart's men were seeing more than panicked Yankees now. The

townspeople were coming out to cheer them, especially when they discovered that there were three Virginia regiments in the column. After

two years of harsh occupation, they were overjoyed to see their own

boys striding proudly down their streets. There had been altogether too

much of New York and Massachusetts's swagger. They looked for their

own 17th Virginia but could not find them; they languished at that moment in the defenses of Richmond.7 But these boys would do. Lee, whose hometown was Alexandria, had been sure to find them the guides they

needed to go straight to Battery Rogers. They hurried down the main

thoroughfare of Washington Street until they came to Jefferson Street,

where they turned east to rush down to the river. They burst through the

battery's unguarded gate just as the gun crews were cheering the death

of Onyx.

From Greyhound, Dunlop saw the guns go silent, then the Stars and

Stripes pulled down to be replaced by Confederate colors, the Stars and

Bars in the upper left corner on a field of white. Infantry swarmed the

parapets to wave their hats and cheer on the British. The crews of the

passing ships returned their cheers. Washington was a little more than

four miles upriver. The thunder of Lee's guns bounced over the water.

Victory was offering her laurels.

WASHINGTON NAVY YARD, WASHINGTON, D.C.,

7:00 AM, OCTOBER 28, 1863

As the rumble of guns came closer up the river, the activity at the Navy

Yard leaped into a higher gear. Unlike the huge Army supply complex

at Alexandria, the Navy Yard was more like a single, well-functioning

ship." Her crew, the mechanics, and naval personnel had worked well

together for a long time and bonded into a single crew, though larger

than any ship's company. Like a good crew, they did not panic but went

about their duties with zeal and efficiency, every man proud to pull his

own weight and not let the ship down.

Three gunboats pushed off down the Eastern Branch to block the

river. A battery of Dahlgren eleven- and nine-inchers pointed downriver,

manned by the test crews. Anyone who did not have a gun crewman's

job was handed a rifle and formed into the Navy Yard battalion. The

Yard intended to fight.

Lowe's balloons were filled and ready to ascend. The Yard commander ordered him up the instant he could go. Lowe noted that the

wind had been blowing to the south-southeast. In twenty minutes, he, a

telegrapher, and Zeppelin were floating above the city, held taut by four

strong cables as the dawn's light flooded over the city. The strong, slanted autumn morning sun illuminated the panorama in gold. He thought

it would have been more scenic but for the banks of rising gunpowder smoke and the moving masses on land and ships on the river. He began

to dictate to the telegraph operator.