A Rainbow of Blood: The Union in Peril an Alternate History (41 page)

Read A Rainbow of Blood: The Union in Peril an Alternate History Online

Authors: Peter G. Tsouras

Tags: #(¯`'•.¸//(*_*)\\¸.•'´¯)

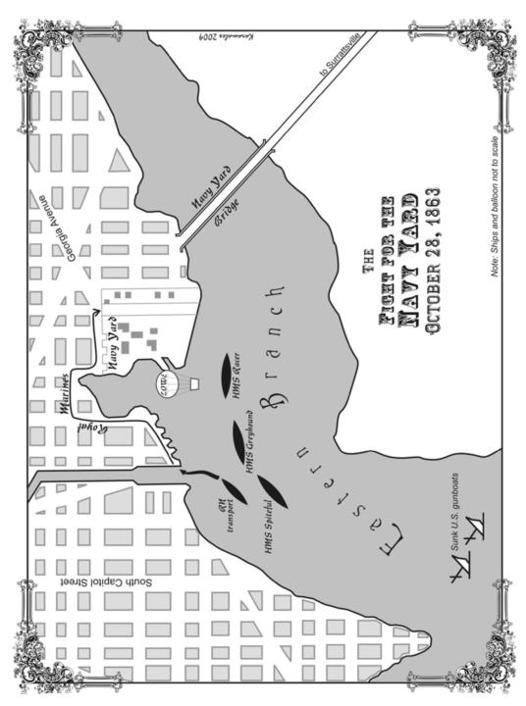

Suddenly the balloon began to move down the street as the windlasses let out more of their cable. In minutes, the two were hovering over the gate itself, now unmistakable to the enemy below. Bullets whizzed

up at the dying balloon like a swarm of angry bees, holing it in dozens of

places. Lowe felt the sting of a bullet and sagged to the basket floor, the

blood gushing down his leg. Cushing tore a strip from his coat and made

a tourniquet with a board from the broken ammunition box. They were

now at three hundred feet.

Lowe leaned on the basket wall, willing himself to fight off the

shock trying to creep over him. His hand grasped the grenade box and

felt the cool, oblong body of one of the 5-pound Ketchums. Instinctively,

his fingers closed on it. Cushing looked at him. "We're too far away to

drop them. Wait."

The lieutenant spun around and fell to his knees clutching his left

forearm. Blood trickled down his sleeve to soak his white shirt cuff. He

looked at Lowe and smiled. "Well, Colonel, we've had quite a run."

They heard the shrill commands of officers below. "What is it?"

asked Lowe. The lieutenant peered over the basket. "Looks like they're

going to charge." Lowe held up a grenade by the rod that connected the

bomb to the fins. He pulled the safety off and handed it to Cushing. The

lieutenant pulled himself up to his feet, nursing his wounded forearm.

The enemy was rushing the gate below with bayonets while others fired

in support from buildings across the street.

Cushing pulled back his right arm and threw the grenade straight

out to give it the maximum reach. It arced out and then curved down

and fell in front of the officer leading the attack. Its contact fuse struck

the brick pavement and exploded. The officer and two men went down.

The rest surged past. Cushing felt Lowe strike his leg with another

grenade. He threw it, and then a third, and more as fast as Lowe could

strip the safeties and hand them up. They sailed out and down every

five to eight seconds, thinning the Royal Marines' numbers but not their

determination. A score closed on the gate with the bayonet to meet the

last of the U.S. Marines standing over their dead and wounded. The

bayonets flicked out and hack like viper tongues, both sides were experts

in the deadly drill with cold steel. More of the British ran from their

firing support positions to reinforce the attack on the gate. The Americans were wedged back in the narrow opening, barely a half dozen on

their feet stabbing and parrying, leaving the red-coated bodies to lie among the blue. The Royal Marines would not be stopped, and they had

the numbers.

"More grenades!" Cushing shouted as he threw them down as fast

as he could into the red mass pushing through the gate. A few exploded,

but most just struck the packed Royal Marines, and their bodies were not

resistant enough to detonate the fuses. The impact of a 5-pound metal

object from two hundred feet was dangerous enough but only as much

as so many rocks. Another bullet tore through his shoulder. He swayed

on his feet before sinking to his knees, pressing his head against the

wicker basket.

From below came the cries of "Board 'em! Board 'em!" and then a

volley of pistol shots. Cushing turned to Lowe, "Hear that? Did you hear

that?" Lowe just looked bewildered until Cushing shouted, "The Navy's

here!"2

What Lowe and Cushing couldn't see from the basket floor was the

rush of the blue jackets of the Navy armed with cutlasses and revolvers

to reinforce the gate. They pushed past the exhausted Marines to fire

their pistols into the packed British almost through the gate. With six

shots at point blank range, the Navy Colts were great killers. Lowe and

Cushing sank bleeding to the basket floor as the balloon was giving up

the ghost, its descent accelerating as the weight of its fabric overpowered

the remaining gas. At fifty feet, it collapsed and fell over the basket; both

plummeted directly over the gate. The basket impaled itself on a turret's

point to sag to one side, pulled down by the weight of the fabric spilling

to the ground. Blood dripped through the torn wicker onto the turret's

gray slate tiles 3

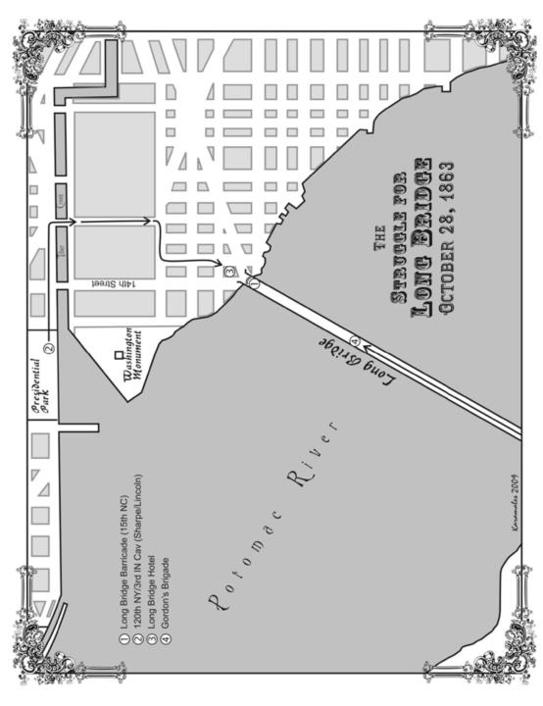

LONG BRIDGE HOTEL, WASHINGTON, D.C.,

11:10 Ann, OCTOBER 28, 1863

Sharpe bounded up the stairs, jumping over the debris strewn by the

cannonballs from the guns that were now in Rebel hands defending the

approach to the Long Bridge. The hotel was only a hundred yards from

the Confederate barricades. Sharpe was led into a room at the top of the

stairs by one of his Horse Marines who had a dripping wad of tobacco in

his cheek. Sharpe saw several more men shooting out through windows.

One of them suddenly threw his arms up and fell backward, a clean red hole in his forehead. Sharpe crawled over to one of the splintered holes

in the wall. He peered though at an angle so as not present a straight

shot to any Rebel Daniel Boone.

The hotel groaned as another cannonball smashed through. The

Tar Heels were behind the barricades effectively adding their rifle fire to

that of the guns. A dozen of the Rebels were strewn in the street after an

attempt to charge the houses had left them as testaments to the volume

and accuracy of the repeater's fire. But the rest were snug behind their

barricade, returning a volume of fire equal to the few Hoosiers in the

house windows. They had only to hold until relieved.

Sharpe scrambled out of the room and climbed the ladder to the attic, and from there out a window onto the reverse roof. He crawled up

and over the shingles to poke his head over the roof peak near the chimney and laid his glasses on the edge. He could see right down the Long

Bridge to the Virginia shore. A bullet splintered a shingle just below his

glasses. Another sung overhead. His presence was known, but he needed to see what was happening. In quick succession, the Stars and Stripes

fell from the fort's flagpole. The Stars and Bars rose quickly in its place.

A mass of men closed on the bridge, their red battle flags clustered over

them. That was enough, especially when another bullet blew splinters

into his face. He slid down the roof and climbed back into the house to

fly down the stairs.

Tappen was waiting, kneeling behind the next house. As soon as he

saw Sharpe dash out the door, he ran over to meet him. Every eye in the

regiment turned to follow the two men. The 120th was strung out, hiding

behind the flimsy wooden buildings on 15th Street, one street over from

that leading directly to the bridge. Lincoln, too, came over to the two,

hemmed in by four guards, human shields. Sharpe had come to terms

with the man's insistence to come along, but he had put the fear of God

into the guard detail that if anything happened to Lincoln, it better be because they were all dead. 4

Lincoln was too late to hear Sharpe's orders as Tappen ran past

him, and Sharpe was not inclined to take the time to explain. Lincoln

could only watch, and he had the good sense not to slow down with

questions men about to go into battle. Instead, all he had to do was

observe as Tappen's brief commands were translated into a burst of action. The crew of a coffee mill gun pulled their piece toward the back of the hotel and quickly manhandled it through the door. Lincoln peered in

after them and saw the grunting men begin to drag it from step to step

up the stairs. The gun captain kicked wreckage off the treads to clear the

way. Once on the landing, he looked into the first bedroom where the

two cavalrymen were firing from the windows. He waved to them, but

they only glanced his way. He was turning to help pull the gun in when

the room exploded. Splinters, pieces of lathe, and plaster flew through

the door. He threw himself to the floor. The dust had not even begun

to settle when he looked in again. "Mother of God," he muttered and

crossed himself. The cavalrymen were bloody bundles of rags slumped

against the opposite wall where the bursting shell had thrown them. Another large hole gaped in the wall.

"Bring it in, boys," the gun captain said, pointing to the new hole

in the wall. He moved to look out the hole when a bullet came through

to nick his ear. He clapped his hand to it and felt the blood ooze through

his fingers. Now it was personal. Waving his fist through the hole, he

shouted, "Shoot at me, will you!" Then turning to the crew, he said,

"Push her up right here!" The gun slid through the debris and poked its

barrel out the hole. The gunner depressed its elevation to sight on the

cannon crews behind the barricade.

"Load!" shouted the gun captain. A loader put the ammunition into

the hopper. The gunner began to turn the crank to feed the cartridges

into the revolving cylinder. In turn, the cylinder fed the first cartridge

into the chamber. The gunner looked at the gun captain. "Fire," he said.

The crank turned, struck the firing cap, and the first bullet shot from

the barrel. The next turn of the crank ejected the cartridge case and fed

another bullet into the chamber. To the ear it was, "click-bang, clickbang, click bang."5 That first bullet went straight into the clustered Rebel

gunners. Now the gunner rotated the crank faster and faster, until the

click-bang blurred into the sound of a high-speed machine hammer. He

only stopped when there were no more men standing by the gun. He

swiveled the barrel left to take another gun crew under fire. He stitched

the stream of bullets first into the enemy gunner, who had just pulled

the lanyard back to fire the gun. The gunner's arm went slack as the bullets disintegrated his head. The gun captain rushed over to pick up the

lanyard but walked into the bullet stream and was knocked over the gun traces. Only the men quick enough to throw themselves behind the barricade survived.6

By now, three other coffee mill guns were in action, sweeping the

riflemen from their firing positions behind the barricade. The Tar Heels'

first rank simply melted away as the guns swept back and forth, throwing the dead and wounded, struck in the upper chest or head, back into

the second rank. The survivors fell to the ground and huddled behind

the barricade, shocked by the speed and violence of the assault. These

were veterans, but they had never seen such a storm of bullets. It was the

moment Tappen had been waiting for. The sword rasped from his scabbard. The men who had been kneeling behind the houses now jumped to

their feet. He led them in a run in a column of companies. Not a man fell

to enemy fire as they closed the distance. The first rank easily topped the

barricade and jumped down inside. The struggle was short.'

Lincoln looked carefully around the building to see the Rebel prisoners being double-timed out of the barricade and rushed up 14th Street

under guard to get them out of the way of temptation before they recovered from their shock. The New Yorkers dragged the guns back through

the barricade to their original positions to defend the bridge. The coffee

mill gun crews on signal rushed their pieces down to the barricade and

lined it from end to end next to the cannons. Wagons rushed up to unload boxes of ammunition to be stacked next to each gun. Sharpe stood

on the barricade and looked down the bridge at the Confederate battle

flags filling the first half of the bridge. They seemed to be rushing forward on the crest of a human wave. Tappen put four companies behind

the guns and three on either side of the bridge to fire laterally into it.

Lincoln was the last to come forward, his big stride comically constrained by his guards whom he topped by at least two heads. He came

up to Sharpe, his stovepipe hat towering higher than anything but the

colors posted behind them. The breeze to the south gently unfurled the

national flag. Someone shouted, "Here they come!"8

FORT RUNYON, VIRGINIA SIDE OF THE WASHINGTON DEFENSES,

11:15 Ann, OCTOBER 28, 1863

From the fort's battered observation tower, Lee and his staff had the

grandest view of Early's division surging onto the Long Bridge, their

red battle flags waving aggressively above the tight-packed columns. A horseman whipped his lathered animal through the broken gates, shouting, "Where is General Lee? Where is General Lee?" Lee put down his

glasses to watch the young cavalry courier take the steps two at a time

onto the platform. He could not be more than sixteen, the peach-fuzz

bloom of early Southern chivalrous manhood on him, despite the sweat

and dirt and the ragged uniform.