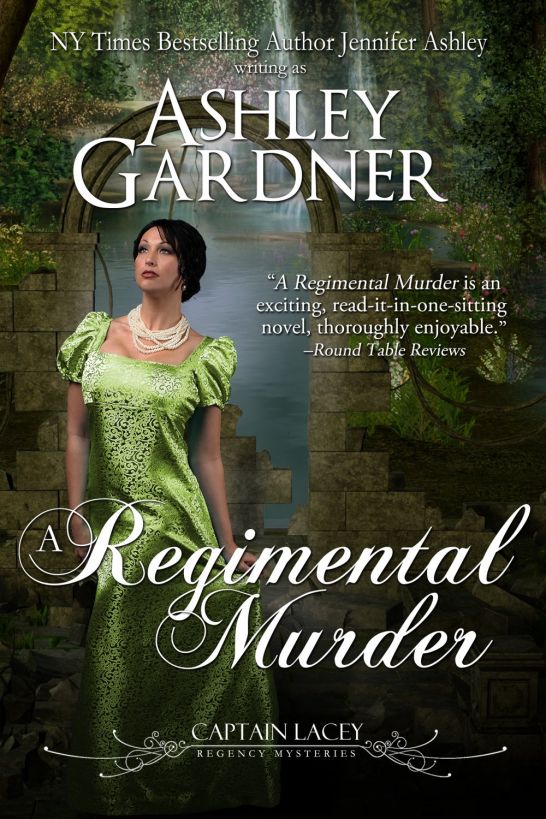

A Regimental Murder

Read A Regimental Murder Online

Authors: Ashley Gardner

Tags: #mystery, #murder mystery, #england, #historical, #cozy mystery, #london, #regency, #peninsular war, #captain lacey

A Regimental Murder

by Ashley Gardner

Book 2 of the Captain Lacey Regency Mysteries

A Regimental Murder

Copyright 2004 and 2011 by Jennifer Ashley (Ashley

Gardner)

All rights reserved.

Published 2011 by Jennifer Ashley (Ashley

Gardner)

Smashwords Edition, License Notes

This ebook is licensed for your personal enjoyment

only. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner

whatsoever without written permission from the author. If you would

like to share this book with another person, please purchase an

additional copy for each recipient. Thank you for respecting the

hard work of this author.

This book is a work of fiction. The names,

characters, places, and incidents are products of the writer's

imagination or have been used fictitiously and are not to be

construed as real. Any resemblance to persons, living or dead,

actual events, locales or organizations is entirely

coincidental.

* * * * *

Chapter One

London, 1816

A new bridge was rising to cross the Thames

just south and east of Covent Garden, a silent hulk of stone and

scaffolding slowly stretching its arches across the river. I walked

down to this unfinished bridge one sweltering July night through

darkness that belonged to pickpockets and game girls, from Grimpen

Lane to Russel Street through Covent Garden, its stalls shut up and

silent, along Southampton Street and the Strand to the pathways

that led to the bridge.

I walked to escape my dreams. I had dreamed

of a Spanish summer, one as hot as this, but with dry breezes from

rocky hillsides under a baking sun. The long days came back to me

and the steamy rains that muddied the roads and fell on my tent

like needles in the night. The warmth took me back to the days I

had been a cavalry captain, and to one particular night when it had

stormed and things had changed for me.

Now I was in London, Iberia far away. The

damp warmth of cobblestones caressed my feet, soft rain striking my

face and rolling in little rivulets down my nose. The hulk of the

bridge was silent, a dark presence not yet born.

That is not to say it was deserted. A street

theatre distracted passersby on the Strand and game girls stood at

the edges of the pavement. A threesome of burly men, arm in arm and

smelling of ale, pushed through singing a happy tune off-key. They

slithered and dodged among wheeled conveyances, never loosening

their hold on one another. Their merry song drifted into the

night.

A woman brushed past me, making for the

tunnel of darkness that led to the bridge. Droplets of rain

sparkled on her dark cloak, and I glimpsed beneath her hood a fine,

sculpted face and the glitter of jewels. She passed so close to me

that I saw the shape of each slender gloved finger that had held

her cloak, and the fine chain of gold that adorned her wrist.

She was a furtive shadow in the midst of the

city night, a lady where no lady should be. She was alone--no

footman or maid pattered after her, holding slipper box or lantern.

She was dressed for the opera or the theatre or a Mayfair ballroom,

and yet she hastened here, to the dark of the incomplete

bridge.

She interested me, this lady, pricking the

curiosity beneath my melancholia. She might, of course, be a high

flyer, an upper-class woman of dubious reputation, but I did not

think so. High flyers were even more prone than ladies of quality

to shutting themselves away in gaudy carriages and taking great

care of their clothes and slippers. Also, this woman did not carry

herself like a lady of doubtful morals, but like a lady who knew

she was out of place and strove to be every inch a lady even

so.

I turned, my curiosity and alarm aroused, and

followed her.

Darkness quickly closed on us, the soft rain

our only companion. She walked out onto an unfinished arch of the

bridge, slippers whispering on boards laid over stones.

I quickened my steps. The boards moved

beneath my feet, the hollow sound carrying to her. She looked back,

her face pale in the darkness. Her cloak swirled back to reveal a

dove gray gown, and her slender legs in white stockings flashed

against the night.

She reached the crest of the arch. The rain

thickened, a gust of wind blowing it like mist across the bridge.

When it cleared, a shadow detached itself from the dark arms of

scaffolding and moved toward her. The woman started, but did not

flee.

The person--man or woman, I could not tell

which--bent to her, speaking rapidly. The lady appeared to listen,

then she stepped back. "No," she said clearly. "I cannot."

The shadow leaned forward, hands moving in

persuasive gestures. She backed away, shaking her head.

Suddenly, she cried out, turned, started to

run. The assailant lunged at her, and I heard the ring of a

knife.

I ran forward. The assailant--male--looked

up, saw me coming. I was a large man, and I carried a walking

stick, within which was concealed a stout sword. Perhaps he knew

who I was, perhaps he'd seen me and my famous temper at work. In

any event, he flung the woman from him and fled.

She landed hard on the stones and boards, too

near the edge. I snatched at the assailant, but his knife flashed

in the rain, catching me across my palm. I grunted. He scuttled

away into the darkness, disappearing in a wash of rain.

I let him go. I balanced myself on the

slippery boards and made my way to her. To my left, empty air rose

from the roiling Thames, mist and hot rain and foul odors. One

misstep and I would plunge down into the waiting, noisome

river.

The woman lay facedown, her body half over

the edge. Her cloak tangled her so that she could not roll to

safety, and her hands worked fruitlessly to pull herself to the

firm stones.

I leaned down, seized her about her waist,

and hauled her back to the middle of the bridge. She cringed from

me, her hands strong as she pushed me away.

"Carefully," I said. "He is gone. You are

safe."

Her hood had fallen back. The jewels I'd

glimpsed were diamonds, a fine tiara of them. They sparkled against

her dark hair, which lay in snarls over her cloak.

"Who was he?" I asked in s gentle voice.

She looked about wildly, as though unsure of

who I meant. "I do not know. A--a beggar, I think."

One with a sharp knife. My hand stung and my

glove was ruined.

I helped her to her feet. She clung to me a

moment, her fright still too close.

Gradually, as the rain quieted into a soft

summer shower, she returned to herself again. Her hands uncurled

from my coat, and her panicked grip relaxed.

"Thank you," she said. "Thank you for helping

me."

I said something polite, as though I had

merely opened a door for her at a soiree.

I led her off the bridge and out of the

darkness, back to the solid reality of the Strand. I kept a sharp

eye out for her assailant, but I saw no one. He had fled.

Our adventure had not gone without attention.

By the time we reached the Strand, a small crowd had gathered to

peer curiously at us. A group of ladies in tawdry finery looked the

woman over.

"Why'd she go out there, then?" one remarked

to the crowd in general.

"Tried to throw herself over," another

answered.

"Belly-full, I'd wager."

The second nodded. "Most like."

The woman appeared not to hear them, but she

moved closer to me, her hand tightening on my sleeve.

A spindly man in faded black fell in beside

us as we moved on. He grinned, showing crooked teeth and bathing me

with coffee-scented breath. "Excellent work, Captain. How brave you

are."

I knew him. The man's name was Billings, and

he was a journalist, one of those damned insolent breed who dressed

badly and followed the rich and prominent, hoping for a breath of

scandal. Billings hung about the theatres at Drury Lane and Covent

Garden, waiting for members of the haut ton to do something

indiscreet.

I toyed with the idea of beating him off, but

knew that such an action would only replay itself in the paragraphs

of whatever scurrilous story he chose to write.

The curious thing was, the lady seemed to

recognize him. She pressed her face into my sleeve, not in a

gesture of fear, but betraying a wish to hide.

His grin grew broader. He saluted me and

sauntered off, no doubt to pen an entirely false version of events

for the

Morning Herald

.

I led the lady along the Strand toward

Southampton Street. She was still shaking and shocked and needed to

get indoors.

"I want to take you home," I said. "You must

tell me where that is."

She shook her head vehemently. "No." Her

voice was little more than a scratch. "Not home. Not there."

"Where, then?"

But she would not give me an alternate

direction, no matter how much I plied her. I wondered where she had

left her conveyance, where her retinue of servants waited for her.

She offered nothing, only moved swiftly along beside me, head bent

so I could not see her face.

"You must tell me where your carriage is," I

tried again.

She shook her head, and continued to shake it

no matter how I pleaded with her. "All right, then," I said, at my

wit's end. "I will take you to a friend who will look after you.

Mrs. Brandon is quite respectable. She is the wife of a

colonel."

My lady stopped, pale lips parting in

surprise. Her eyes, deep blue I saw now that we stood in the light,

widened. "Mrs. Brandon?" Suddenly, she began to laugh. Her hands

balled into tight fists, and she pressed them into her stomach,

hysteria shaking her.

I tried to quiet her, but she laughed on,

until at last the broken laughs turned to sobs. "Not Mrs. Brandon,"

she gasped. "Oh, please, no, never that. I will go with you,

anywhere you want. Take me to hell if you like, but not home, and

not to Mrs. Brandon, for God's sake. That would never do."

*** *** ***

In the end, I took her to my rooms in Grimpen

Lane, a narrow cul-de-sac off Russel Street near Covent Garden

market.

The lane was hot with the summer night. My

hardworking neighbors were in their beds, though a few street girls

lingered in the shadows, and a gin-soaked young man lay flat on his

back not far from the bake shop. If the man did not manage to drag

himself away, the game girls would no doubt rob him blind, if they

hadn't already.

I stopped at a narrow door beside the bake

shop, unlocked and opened it. Stuffy air poured down at us. The

staircase inside had once been grand, and the remnants of an

idyllic mural could be seen in the moonlight--shepherds and

shepherdesses pursuing each other across a flat green landscape, a

curious mixture of innocence and lust.

"What is this place?" my lady asked in

whisper.

"Number 5, Grimpen Lane," I answered as I led

her upstairs and unlocked the door on the first landing. "In my

lighter moments, I call it home."

Behind the door lay my rooms, once the

drawing rooms of whatever wealthy family had lived here a century

ago. The flat above mine was quiet, which meant that Marianne

Simmons, my upstairs neighbor, was either on stage in Drury Lane or

tucked away somewhere with a gentleman. Mrs. Beltan, the landlady

who ran the bake shop below, lived streets away with her sister.

The house was empty and we were alone.

I ushered the woman inside. She remained

standing in the middle of the carpet, chafing her hands as I

stirred the embers that still glowed in my grate. The night was

warm, but the old walls held a chill that no amount of sun could

leach away. Once a tiny fire crackled in the coals, I opened the

windows, which I'd left closed to keep birds from seeking shelter

in my front room. The breeze that had sprung up at the river barely

reached Grimpen Lane, but the open window at least moved the

stagnant air.

By the fire's light, I saw that the woman was

likely in her late thirties, or fortyish as I was. She had a

classic beauty that the bloody scratches on her cheek could not

mar, a clean line of jaw, square cheekbones, arched brows over

full-lashed eyes. Faint lines feathered from her eyes and corners

of her mouth, not age, but weariness.

I took her wet cloak from her, then led her

to the wing chair near the fire and bade her sit. I stripped her

ruined slippers from her ice-cold feet then fetched a blanket from

my bed and tucked it around her. She sat through the proceedings

without interest.

I poured out a large measure of brandy from a

fine bottle my acquaintance Lucius Grenville had sent me and

brought it to her. The glass shook against her mouth, but I held it

steady and made her drink every drop. Then I brought her

another.