A Short History of the World (20 page)

Read A Short History of the World Online

Authors: H. G. Wells

The Development of Doctrinal Christianity

In the four gospels we find the personality and teachings of Jesus but very little of the dogmas of the Christian Church. It is in the epistles, a series of writings by the immediate followers of Jesus, that the broad lines of Christian belief are laid down.

Chief among the makers of Christian doctrine was St Paul. He had never seen Jesus nor heard him preach. Paul's name was originally Saul, and he was conspicuous at first as an active persecutor of the little band of disciples after the crucifixion. Then he was suddenly converted to Christianity, and he changed his name to Paul. He was a man of great intellectual vigour and deeply and passionately interested in the religious movements of the time. He was well versed in Judaism and in the Mithraism and Alexandrian religion of the day. He carried over many of their ideas and terms of expression into Christianity. He did very little to enlarge or develop the original teaching of Jesus, the teaching of the Kingdom of Heaven. But he taught that Jesus was only not the promised Christ, the promised leader of the Jews, but also that his death was a sacrifice, like the deaths of the ancient sacrificial victims of the primordial civilizations, for the redemption of mankind.

When religions flourish side by side they tend to pick up each other's ceremonial and other outward peculiarities. Buddhism, for example, in China has now almost the same sort of temples and priests and uses as Taoism, which follows in the teachings of Lao Tse. Yet the original teachings of Buddhism and Taoism were almost flatly opposed. And it reflects no doubt or discredit upon the essentials of Christian teaching that it took over not merely such formal things as the shaven priest, the votive

offering, the altars, candles, chanting and images of the Alexandrian and Mithraic faiths, but adopted even their devotional phrases and their theological ideas. All these religions were flourishing side by side with many less prominent cults. Each was seeking adherents, and there must have been a constant going and coming of converts between them. Sometimes one or other would be in favour with the government. But Christianity was regarded with more suspicion than its rivals because, like the Jews, its adherents would not perform acts of worship to the God Caesar. This made it a seditious religion, quite apart from the revolutionary spirit of the teachings of Jesus himself.

St Paul familiarized his disciples with the idea that Jesus, like Osiris, was a god who died to rise again and give men immortality. And presently the spreading Christian community was greatly torn by complicated theological disputes about the relationship of this God Jesus to God the Father of Mankind. The Arians taught that Jesus was divine, but distinct from and inferior to the Father. The Sabellians taught that Jesus was merely an aspect of the Father, and that God was Jesus and Father at the same time just as a man may be a father and an artificer at the same time; and the Trinitarians taught a more subtle doctrine that God was both one and three, Father, Son and Holy Spirit. For a time it seemed that Arianism would prevail over its rivals, and then after disputes, violence and wars, the Trinitarian formula became the accepted formula of all Christendom. It may be found in its completest expression in the Athanasian Creed.

We offer no comment on these controversies here. They do not sway history as the personal teaching of Jesus sways history. The personal teaching of Jesus does seem to mark a new phase in the moral and spiritual life of our race. Its insistence upon the universal Fatherhood of God and the implicit brotherhood of all men, its insistence upon the sacredness of every human personality as a living temple of God, was to have the profoundest effect upon all the subsequent social and political life of mankind. With Christianity, with the spreading teachings of Jesus, a new respect appears in the world for man as man. It may be true, as hostile critics of Christianity have urged, that

St Paul preached obedience to slaves, but it is equally true that the whole spirit of the teachings of Jesus preserved in the gospels was against the subjugation of man by man. And still more distinctly was Christianity opposed to such outrages upon human dignity as the gladiatorial combats in the arena.

Throughout the first two centuries after Christ, the Christian religion spread throughout the Roman Empire, weaving together an ever-growing multitude of converts into a new community of ideas and will. The attitude of the emperors varied between hostility and toleration. There were attempts to suppress this new faith in both the second and third centuries; and finally in 303 and the following years a great persecution under the Emperor Diocletian. The considerable accumulations of Church property were seized, all Bibles and religious writings were confiscated and destroyed, Christians were put out of the protection of the law and many executed. The destruction of the books is particularly notable. It shows how the power of the written word in holding together the new faith was appreciated by the authorities. These âbook religions', Christianity and Judaism, were religions that educated. Their continued existence depended very largely on people being able to read and understand their doctrinal ideas. The older religions had made no such appeal to the personal intelligence. In the ages of barbaric confusion that were now at hand in western Europe it was the Christian Church that was mainly instrumental in preserving the tradition of learning.

The persecution of Diocletian failed completely to suppress the growing Christian community. In many provinces it was ineffective because the bulk of the population and many of the officials were Christian. In 311 an edict of toleration was issued by the associated Emperor Galerius, and in 324 Constantine the Great, a friend and on his deathbed a baptized convert to Christianity, became sole ruler of the Roman world. He abandoned all divine pretensions and put Christian symbols on the shields and banners of his troops.

In a few years Christianity was securely established as the official religion of the Empire. The competing religions disappeared or were absorbed with extraordinary celerity, and in

390 Theodosius the Great caused the great statue of Jupiter Serapis at Alexandria to be destroyed. From the outset of the fifth century onward the only priests or temples in the Roman Empire were Christian priests and temples.

The Barbarians Break the Empire into East and West

Throughout the third century the Roman Empire, decaying socially and disintegrating morally, faced the barbarians. The emperors of this period were fighting military autocrats, and the capital of the Empire shifted with the necessities of their military policy. Now the imperial headquarters would be at Milan in north Italy, now in what is now Serbia at Sirmium or Nish, now in Nicomedia in Asia Minor. Rome halfway down Italy was too far from the centre of interest to be a convenient imperial seat. It was a declining city. Over most of the Empire peace still prevailed and men went about without arms. The armies continued to be the sole repositories of power; the emperors, dependent on their legions, became more and more autocratic to the rest of the Empire and their state more and more like that of the Persian and other oriental monarchs. Diocletian assumed a royal diadem and oriental robes.

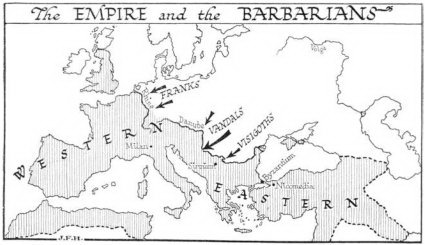

All along the imperial frontier, which ran roughly along the Rhine and Danube, enemies were now pressing. The Franks and other German tribes had come up to the Rhine. In north Hungary were the Vandals; in what was once Dacia and is now Rumania, the Visigoths or West Goths. Behind these in south Russia were the East Goths or Ostrogoths, and beyond these again in the Volga region the Alans. But now Mongolian peoples were forcing their way towards Europe. The Huns were already exacting tribute from the Alans and Ostrogoths and pushing them to the west.

In Asia the Roman frontiers were crumpling back under the push of a renascent Persia. This new Persia, the Persia of the

Sassanid kings, was to be a vigorous and on the whole a successful rival of the Roman Empire in Asia for the next three centuries.

A glance at the map of Europe will show the reader the peculiar weakness of the Empire. The river Danube comes down to within a couple of hundred miles of the Adriatic Sea in the region of what is now Bosnia and Serbia. It makes a square re-entrant angle there. The Romans never kept their sea communications in good order, and this 200 mile strip of land was their line of communication between the western Latin-speaking part of the Empire and the eastern Greek-speaking portion. Against this square angle of the Danube the barbarian pressure was greatest. When they broke through there it was inevitable that the Empire should fall into two parts.

A more vigorous empire might have thrust forward and reconquered Dacia, but the Roman Empire lacked any such vigour. Constantine the Great was certainly a monarch of great devotion and intelligence. He beat back a raid of the Goths from just these vital Balkan regions, but he had no force to carry the frontier across the Danube. He was too preoccupied with the internal weaknesses of the Empire. He brought the solidarity and moral force of Christianity to revive the spirit of the declining empire, and he decided to create a new permanent capital at Byzantium upon the Hellespont. This new-made Byzantium, which was rechristened Constantinople in his honour, was still building when he died. Towards the end of his reign occurred a remarkable transaction. The Vandals, being pressed by the Goths, asked to be received into the Roman Empire. They were assigned lands in Pannonia, which is now that part of Hungary west of the Danube, and their fighting men became nominally legionaries. But these new legionaries remained under their own chiefs. Rome failed to digest them.

Constantine died working to reorganize his great realm, and soon the frontiers were ruptured again and the Visigoths came almost to Constantinople. They defeated the Emperor Valens at Adrianople and made a settlement in what is now Bulgaria, similar to the settlement of the Vandals in Pannonia. Nominally they were subjects of the emperor, practically they were conquerors.

From

AD

379 to 395 reigned the Emperor Theodosius the Great, and while he reigned the Empire was still formally intact. Over the armies of Italy and Pannonia presided Stilicho, a Vandal, over the armies in the Balkan peninsula, Alaric, a Goth. When Theodosius died at the close of the fourth century he left two sons. Alaric supported one of these, Arcadius, in Constantinople, and Stilicho the other, Honorius, in Italy. In other words Alaric and Stilicho fought for the Empire with the princes as puppets. In the course of their struggle Alaric marched into Italy and after a short siege took Rome (

AD

410).

The opening half of the fifth century saw the whole of the Roman Empire in Europe the prey of robber armies of barbarians. It is difficult to visualize the state of affairs in the world at that time. Over France, Spain, Italy and the Balkan peninsula, the great cities that had flourished under the Early Empire still stood, impoverished, partly depopulated and falling into decay. Life in them must have been shallow, mean and full of uncertainty. Local officials asserted their authority and went on with their work with such conscience as they had, no doubt in the name of a now remote and inaccessible emperor. The churches went on, but usually with illiterate priests. There was little

reading and much superstition and fear. But everywhere except where looters had destroyed them, books and pictures and statuary and such like works of art were still to be found.

The life of the countryside had also degenerated. Everywhere this Roman world was much more weedy and untidy than it had been. In some regions war and pestilence had brought the land down to the level of a waste. Roads and forests were infested with robbers. Into such regions the barbarians marched, with little or no opposition, and set up their chiefs as rulers, often with Roman official titles. If they were half-civilized barbarians they would give the conquered districts tolerable terms, they would take possession of the towns, associate and intermarry, and acquire (with an accent) the Latin speech; but the Jutes, the Angles and Saxons who submerged the Roman province of Britain were agriculturalists and had no use for towns; they seem to have swept south Britain clear of the Romanized population and they replaced the language by their own Teutonic dialects, which became at last English.

It is impossible in the space at our disposal to trace the movements of all the various German and Slavonic tribes as they went to and fro in the disorganized empire in search of plunder and a pleasant home. But let the Vandals serve as an example. They came into history in east Germany. They settled, as we have told, in Pannonia. Thence they moved somewhen about

AD

425 through the intervening provinces to Spain. There they found Visigoths from south Russia and other German tribes setting up dukes and kings. From Spain the Vandals under Genseric sailed for north Africa (429), captured Carthage (439), and built a fleet. They secured the mastery of the sea and captured and pillaged Rome (455), which had recovered very imperfectly from her capture and looting by Alaric half a century earlier. Then the Vandals made themselves masters of Sicily, Corsica, Sardinia and most of the other islands of the western Mediterranean. They made, in fact, a sea empire very similar in its extent to the sea empire of Carthage 700 odd years before. They were at the climax of their power about 477. They were a mere handful of conquerors holding all this country. In the next century almost all their territory had been reconquered

for the empire of Constantinople during a transitory blaze of energy under Justinian I.

The story of the Vandals is but one sample of a host of similar adventures. But now there was coming into the European world the least kindred and most redoubtable of all these devastators, the Mongolian Huns or Tartars, a yellow people active and able, such as the Western world had never before encountered.