A Short History of the World (29 page)

Read A Short History of the World Online

Authors: H. G. Wells

In 1714 the Elector of Hanover became King of England, adding one more to the list of monarchies half in and half out of the empire.

The Austrian branch of the descendants of Charles V retained the title of Emperor; the Spanish branch retained Spain. But now there was also an emperor of the East again. After the fall of Constantinople (1453), the grand duke of Moscow, Ivan the Great (1462â1505), claimed to be heir to the Byzantine throne and adopted the Byzantine double-headed eagle upon his arms. His grandson, Ivan IV, Ivan the Terrible (1533â1584), assumed the imperial title of Caesar (Tzar). But only in the latter half of the seventeenth century did Russia cease to seem remote and Asiatic to the European mind. The Tzar Peter the Great (1682â1725) brought Russia into the arena of Western affairs. He built a new capital for his empire, Petersburg upon the Neva, that played the part of a window between Russia and Europe, and he set up his Versailles at Peterhof eighteen miles away, employing a French architect who gave him a terrace, fountains, cascades, picture gallery, park and all the recognized appointments of Grand Monarchy. In Russia as in Prussia French became the language of the court.

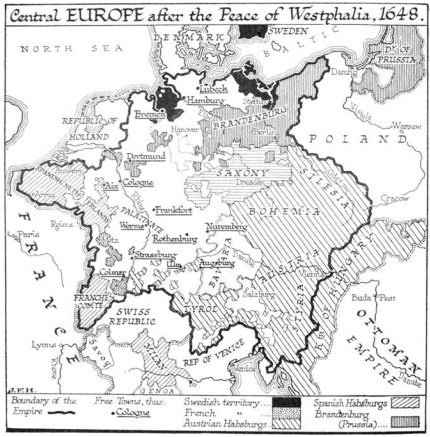

Unhappily placed between Austria, Prussia and Russia was the Polish kingdom, an ill-organized state of great landed proprietors too jealous of their own individual grandeur to permit more than a nominal kingship to the monarch they elected. Her fate was division among these three neighbours, in spite of the efforts of France to retain her as an independent ally. Switzerland at this time was a group of republican cantons; Venice was a republic; Italy like so much of Germany was divided among minor dukes and princes. The Pope ruled like a prince in the papal states, too fearful now of losing the allegiance of the remaining Catholic princes to interfere between them and their

subjects or to remind the world of the commonweal of Christendom. There remained indeed no common political idea in Europe at all; Europe was given over altogether to division and diversity.

All these sovereign princes and republics carried on schemes of aggrandizement against each other. Each one of them pursued a âforeign policy' of aggression against its neighbours and of aggressive alliances. We Europeans still live today in the last phase of this age of the multifarious sovereign states, and still suffer from the hatreds, hostilities and suspicions it engendered.

The history of this time becomes more and more manifestly âgossip', more and more unmeaning and wearisome to a modern intelligence. You are told of how this war was caused by this king's mistress, and how the jealousy of one minister for another caused that. A tittle-tattle of bribes and rivalries disgusts the intelligent student. The more permanently significant fact is that in spite of the obstruction of a score of frontiers, reading and thought still spread and increased and inventions multiplied. The eighteenth century saw the appearance of a literature profoundly sceptical and critical of the courts and policies of the time. In such a book as Voltaire's

Candide

3

we have the expression of an infinite weariness with the planless confusion of the European world.

The New Empires of the Europeans in Asia and Overseas

While central Europe thus remained divided and confused, the western Europeans, and particularly the Dutch, the Scandinavians, the Spanish, the Portuguese, the French and the British, were extending the area of their struggles across the seas of all the world. The printing press had dissolved the political ideas of Europe into a vast and at first indeterminate fermentation, but that other great innovation, the ocean-going sailing ship, was inexorably extending the range of European experience to the furthermost limits of salt water.

The first overseas settlements of the Dutch and Northern Atlantic Europeans were not for colonization but for trade and mining. The Spaniards were first in the field; they claimed dominion over the whole of this new world of America. Very soon, however, the Portuguese asked for a share. The Pope – it was one of the last acts of Rome as mistress of the world – divided the new continent between these two first-comers, giving Portugal Brazil and everything else east of a line 370 leagues west of the Cape Verde islands, and all the rest to Spain (1494). The Portuguese at this time were also pushing overseas enterprise southward and eastward. In 1497 Vasco da Gama had sailed from Lisbon round the Cape to Zanzibar and then to Calicut in India. In 1515 there were Portuguese ships in Java and the Moluccas, and the Portuguese were setting up and fortifying trading stations round and about the coasts of the Indian Ocean. Mozambique, Goa and two smaller possessions in India, Macao in China and a part of Timor are to this day Portuguese possessions.

1

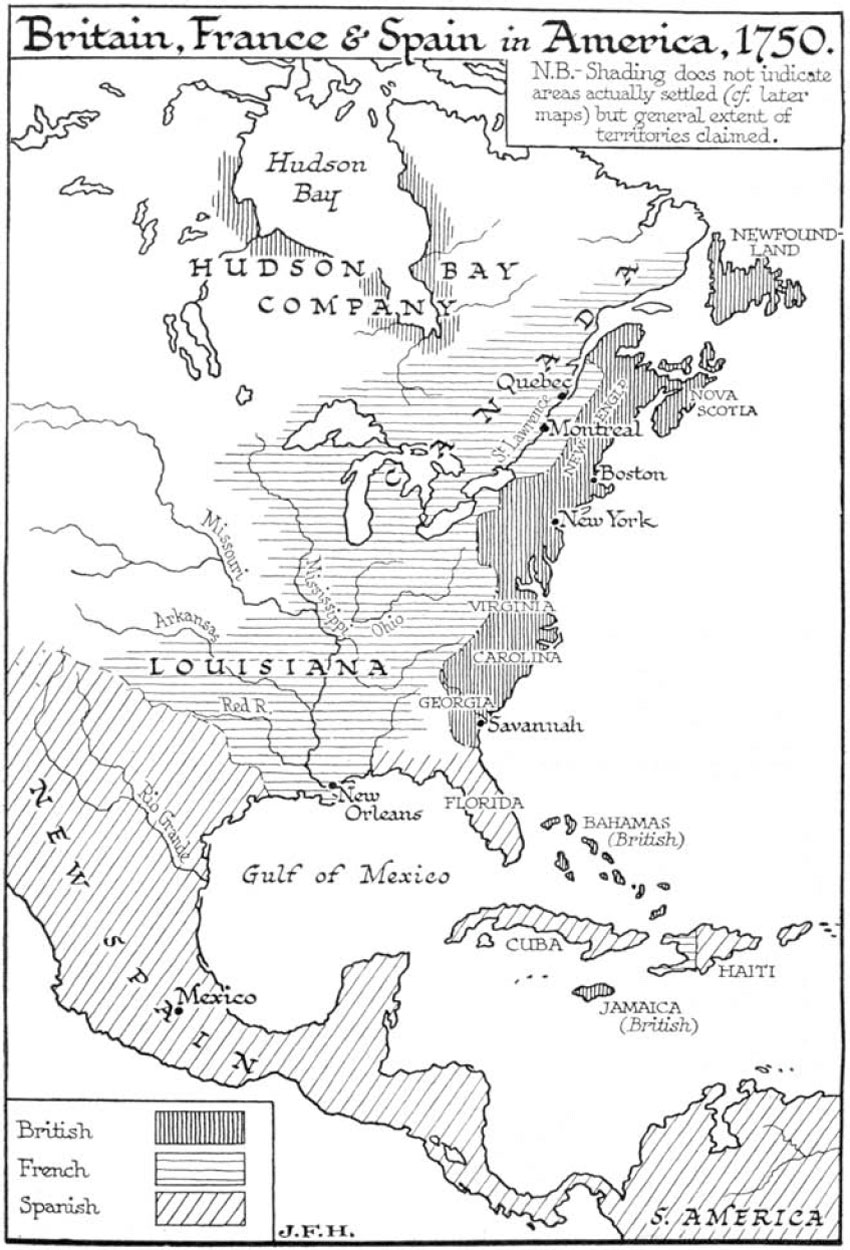

The nations excluded from America by the papal settlement

paid little heed to the rights of Spain and Portugal. The English, the Danes and Swedes, and presently the Dutch, were soon staking out claims in North America and the West Indies, and his Most Catholic Majesty of France heeded the papal settlement as little as any Protestant. The wars of Europe extended themselves to these claims and possessions.

In the long run the English were the most successful in this scramble for overseas possessions. The Danes and Swedes were too deeply entangled in the complicated affairs of Germany to sustain effective expeditions abroad. Sweden was wasted upon the German battlefields by a picturesque king, Gustavus Adolphus, the Protestant ‘Lion of the North’. The Dutch were the heirs of such small settlements as Sweden made in America, and the Dutch were too near French aggressions to hold their own against the British. In the far East the chief rivals for empire were the British, Dutch and French, and in America the British, French and Spanish. The British had the supreme advantage of a water frontier, the ‘silver streak’

2

of the English Channel, against Europe. The tradition of the Latin empire entangled them least.

France has always thought too much in terms of Europe. Throughout the eighteenth century she was wasting her opportunities of expansion in West and East alike in order to dominate Spain, Italy and the German confusion. The religious and political dissensions of Britain in the seventeenth century had driven many of the English to seek a permanent home in America. They struck root and increased and multiplied, giving the British a great advantage in the American struggle. In 1756 and 1760 the French lost Canada to the British and their American colonists, and a few years later the British trading company found itself completely dominant over French, Dutch and Portuguese in the peninsula of India. The great Mongol Empire of Baber, Akbar and their successors had now far gone in decay, and the story of its practical capture by a London trading company, the British East India Company, is one of the most extraordinary episodes in the whole history of conquest.

This East India Company had been originally at the time of its incorporation under Queen Elizabeth no more than a company

of sea adventurers. Step by step they had been forced to raise troops and arm their ships. And now this trading company, with its tradition of gain, found itself dealing not merely in spices and dyes and tea and jewels, but in the revenues and territories of princes and the destinies of India. It had come to buy and sell, and it found itself achieving a tremendous piracy. There was no one to challenge its proceedings. Is it any wonder that its captains and commanders and officials, nay, even its clerks and common soldiers, came back to England loaded with spoils?

Men under such circumstances, with a great and wealthy land at their mercy, could not determine what they might or might not do. It was a strange land to them, with a strange sunlight; its brown people seemed a different race, outside their range of sympathy; its mysterious temples sustained fantastic standards of behaviour. Englishmen at home were perplexed when presently these generals and officials came back to make dark accusations against each other of extortions and cruelties. Upon Clive Parliament passed a vote of censure. He committed suicide in 1774. In 1788 Warren Hastings,

3

a second great Indian administrator, was impeached and acquitted (1792). It was a strange and unprecedented situation in the world's history. The English Parliament found itself ruling over a London trading company, which in its turn was dominating an empire far greater and more populous than all the domains of the British crown. To the bulk of the English people India was a remote, fantastic, almost inaccessible land, to which adventurous poor young men went out, to return after many years very rich and very choleric old gentlemen. It was difficult for the English to conceive what the life of these countless brown millions in the Eastern sunshine could be. Their imaginations declined the task. India remained romantically unreal. It was impossible for the English, therefore, to exert any effective supervision and control over the company's proceedings.

And while the western European powers were thus fighting for these fantastic overseas empires upon every ocean in the world, two great land conquests were in progress in Asia. China had thrown off the Mongol yoke in 1368, and flourished under the great native dynasty of the Mings until 1644. Then the

Manchus, another Mongol people, reconquered China and remained masters of China until 1912. Meanwhile Russia was pushing east and growing to greatness in the world's affairs. The rise of this great central power of the old world, which is neither altogether of the East nor altogether of the West, is one of the utmost importance to our human destiny. Its expansion is very largely due to the appearance of a Christian steppe people, the Cossacks, who formed a barrier between the feudal agriculture of Poland and Hungary to the west and the Tartar to the east. The Cossacks were the wild east of Europe, and in many ways not unlike the wild west of the United States in the middle nineteenth century. All who had made Russia too hot to hold them, criminals as well as the persecuted innocent, rebellious serfs, religious sectaries, thieves, vagabonds, murderers, sought asylum in the southern steppes and there made a fresh start and fought for life and freedom against Pole, Russian and Tartar alike. Doubtless fugitives from the Tartars to the east also contributed to the Cossack mixture. Slowly these border folk were incorporated in the Russian imperial service, much as the Highland clans of Scotland were converted into regiments by the British government. New lands were offered them in Asia. They became a weapon against the dwindling power of the Mongolian nomads, first in Turkestan and then across Siberia as far as the Amur.

The decay of Mongol energy in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries is very difficult to explain. Within two or three centuries from the days of Jengis and Timurlane central Asia had relapsed from a period of world ascendancy to extreme political impotence. Changes of climate, unrecorded pestilences, infections of a malarial type, may have played their part in this recession – which may be only a temporary recession measured by the scale of universal history – of the central Asian peoples. Some authorities think that the spread of Buddhist teaching from China also had a pacifying influence upon them. At any rate, by the sixteenth century the Mongol Tartar and Turkish peoples were no longer pressing outward, but were being invaded, subjugated and pushed back both by Christian Russia in the west and by China in the east.

All through the seventeenth century the Cossacks were spreading eastward from European Russia, and settling wherever they found agricultural conditions. Cordons of forts and stations formed a moving frontier to these settlements to the south, where the Turkomans were still strong and active; to the north-east, however, Russia had no frontier until she reached right to the Pacific…

The American War of Independence

The third quarter of the eighteenth century thus saw the remarkable and unstable spectacle of a Europe divided against itself, and no longer with any unifying political or religious idea, yet through the immense stimulation of men's imaginations by the printed book, the printed map and the opportunity of the new ocean-going shipping, able in a disorganized and contentious manner to dominate all the coasts of the world. It was a planless, incoherent ebullition of enterprise due to temporary and almost accidental advantages over the rest of mankind. By virtue of these advantages this new and still largely empty continent of America was peopled mainly from western European sources, and South Africa and Australia and New Zealand marked down as prospective homes for a European population.

The motive that had sent Columbus to America and Vasco da Gama to India was the perennial first motive of all sailors since the beginning of things â trade. But while in the already populous and productive East the trade motive remained dominant, and the European settlements remained trading settlements from which the European inhabitants hoped to return home to spend their money, the Europeans in America, dealing with communities at a very much lower level of productive activity, found a new inducement for persistence in the search for gold and silver. Particularly did the mines of Spanish America yield silver. The Europeans had to go to America not simply as armed merchants but as prospectors, miners, searchers after natural products and presently as planters. In the north they sought furs. Mines and plantations necessitated settlements. They obliged people to set up permanent overseas

homes. Finally in some cases, as when the English Puritans went to New England in the early seventeenth century to escape religious persecution, when in the eighteenth Oglethorpe

1

sent people from the English debtors' prisons to Georgia, and when in the end of the eighteenth the Dutch sent orphans to the Cape of Good Hope, the Europeans frankly crossed the seas to find new homes for good. In the nineteenth century, and especially after the coming of the steamship, the stream of European emigration to the new empty lands of America and Australia rose for some decades to the scale of a great migration.

So there grew up permanent overseas populations of Europeans, and the European culture was transplanted to much larger areas than those in which it had been developed. These new communities, bringing a ready-made civilization with them to these new lands, grew up, as it were, unplanned and unperceived; the statecraft of Europe did not foresee them, and was unprepared with any ideas about their treatment. The politicians and ministers of Europe continued to regard them as essentially expeditionary establishments, sources of revenue, âpossessions' and âdependencies', long after their peoples had developed a keen sense of their separate social life. And also they continued to treat them as helplessly subject to the mother country long after the population had spread inland out of reach of any effectual punitive operations from the sea.

Because until right into the nineteenth century, it must be remembered, the link of all these overseas empires was the ocean-going sailing ship. On land the swiftest thing was still the horse, and the cohesion and unity of political systems on land was still limited by the limitations of horse communications.

Now at the end of the third quarter of the eighteenth century the northern two-thirds of North America was under the British crown. France had abandoned America. Except for Brazil, which was Portuguese, and one or two small islands and areas in French, British, Danish and Dutch hands, Florida, Louisiana, California and all America to the south was Spanish. It was the British colonies south of Maine and Lake Ontario that first demonstrated the inadequacy of the sailing ship to hold overseas populations together in one political system.

These British colonies were very miscellaneous in their origin and character. There were French, Swedish and Dutch settlements as well as British; there were British Catholics in Maryland and British ultra-Protestants in New England, and while the New Englanders farmed their own land and denounced slavery, the British in Virginia and the south were planters employing a swelling multitude of imported negro slaves. There was no natural common unity in such states. To get from one to the other might mean a coasting voyage hardly less tedious than the transatlantic crossing. But the union that diverse origin and natural conditions denied the British Americans was forced upon them by the selfishness and stupidity of the British government in London. They were taxed without any voice in the spending of the taxes; their trade was sacrificed to British interests; the highly profitable slave trade was maintained by the British government in spite of the opposition of the Virginians who â though quite willing to hold and use slaves â feared to be swamped by an ever-growing barbaric black population.

Britain at that time was lapsing towards an intenser form of monarchy, and the obstinate personality of George III (1760â1820) did much to force on a struggle between the home and the colonial governments.

The conflict was precipitated by legislation which favoured the London East India Company at the expense of the American shipper. Three cargoes of tea which were imported under the new conditions were thrown overboard in Boston harbour by a band of men disguised as Indians (1773). Fighting only began in 1775 when the British government attempted to arrest two of the American leaders at Lexington near Boston. The first shots were fired in Lexington by the British; the first fighting occurred at Concord.

So the American War of Independence began, though for more than a year the colonists showed themselves extremely unwilling to sever their links with the motherland. It was not until the middle of 1776 that the Congress of the insurgent states issued âThe Declaration of Independence'. George Washington, who like many of the leading colonists of the time had had a military training in the wars against the French, was

made commander-in-chief. In 1777 a British general, General Burgoyne, in an attempt to reach New York from Canada, was defeated at Freemans Farm and obliged to surrender at Saratoga. In the same year the French and Spanish declared war upon Great Britain, greatly hampering her sea communications. A second British army under General Cornwallis was caught in the Yorktown peninsula in Virginia and obliged to capitulate in 1781. In 1783 peace was made in Paris, and the Thirteen Colonies from Maine to Georgia became a union of independent sovereign states. So the United States of America came into existence. Canada remained loyal to the British flag.

For four years these States had only a very feeble central government under certain Articles of Confederation, and they seemed destined to break up into separate independent communities. Their immediate separation was delayed by the hostility of the British and a certain aggressiveness on the part of the French which brought home to them the immediate dangers of division. A Constitution was drawn up and ratified in 1788 establishing a more efficient federal government with a president holding very considerable powers, and the weak sense of national unity was invigorated by a second war with Britain in 1812. Nevertheless the area covered by the States was so wide and their interests so diverse at that time, that â given only the means of communication then available â a disintegration of the Union into separate states on the European scale of size was merely a question of time. Attendance at Washington meant a long, tedious and insecure journey for the senators and congressmen of the remoter districts, and the mechanical impediments to the diffusion of a common education and a common literature and intelligence were practically insurmountable. Forces were at work in the world, however, that were to arrest the process of differentiation altogether. Presently came the river steamboat and then the railway and the telegraph to save the United States from fragmentation, and weave its dispersed people together again into the first of great modern nations.

Twenty-two years later the Spanish colonies in America were to follow the example of the Thirteen and break their connexion with Europe. But being more dispersed over the continent and

separated by great mountainous chains and deserts and forests and by the Portuguese empire of Brazil, they did not achieve a union among themselves. They became a constellation of republican states, very prone at first to wars among themselves and to revolutions.

Brazil followed a rather different line towards the inevitable separation. In 1807 the French armies under Napoleon had occupied the mother country of Portugal, and the monarchy had fled to Brazil. From that time on until they separated, Portugal was rather a dependency of Brazil than Brazil of Portugal. In 1822 Brazil declared itself a separate empire under Pedro I, a son of the Portuguese king. But the new world has never been very favourable to monarchy. In 1889 the Emperor of Brazil was shipped off quietly to Europe, and the United States of Brazil fell into line with the rest of republican America.