A Singular Woman (32 page)

Yet on another occasion, Ann wrote, “Wanted to write and let you know how much I enjoyed our time together in London. . . . I realized when we were there how much you actually mean to me. In a world where most people are such bloody hypocrites, your spirit shines like a beautiful star! I never have to go through a lot of crap with you, so to speak. Sounds corny, but I mean it. I love you a lot, kiddo.”

With many of her friends, Ann kept the details of her private life private. Even with some who knew her well, she revealed little about her childhood, her parents, even her marriages. On the subject of her sex life, she was discreet even with close friendsâor so they led me to believe. But opportunities for romance did not end with her second divorce. Carol Colfer, who was also a single American woman in her thirties working in Indonesia, said she and Ann used to talk about people hitting on them. “It was very common,” she said. “A lot of Indonesians like white skin. And, of course, she had quite white skin. We would joke about people bothering us and thinking we were going to be these wildly sexually active folks. We weren't very wild.” If Ann confided on a regular basis in anyone, it appears to have been Suryakusuma. “We were both very sexual,” Suryakusuma told me. “We talked a lot about sex and our sex lives.” Ann was sensual, Suryakusuma said. She took pleasure in, among other things, food and sex. Rens Heringa said she and Ann shared an astrological sign, Sagittarius, thought to signify an adventurous spirit. “I never was interested in Dutch guys, ever,” Heringa said. “She never was really interested in white guys.” According to Suryakusuma, “She used to say she liked brown bums and I liked white bums.”

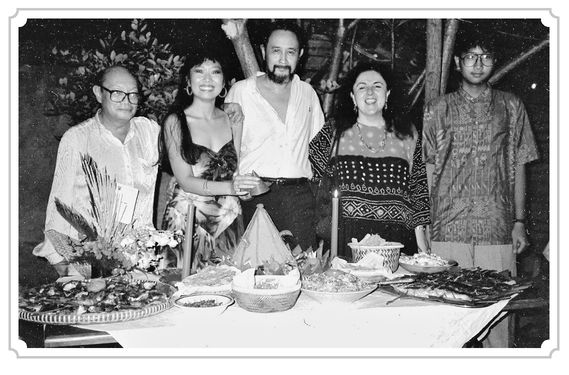

With Ong Hok Ham, Julia Suryakusuma, Ami Priyono, and Aditya Priyawardhana, the son of Julia Suryakusuma and Ami Priyono, July 1989

Ann's secretary at the Ford Foundation, Paschetta Sarmidi, noticed that Ann's eyes “glittered” at the mention of a certain Indonesian man who worked for a bank near the Ford offices.

“You like Indonesians,” Sarmidi observed tentatively. “The first time, you married an African. The second time, you married Lolo. Now you like the man from the bank.”

“She smiled,” recalled Sarmidi, who pressed no further.

Ann loved men, but she did not claim to understand them, Georgia McCauley, who became a close friend of Ann's in Jakarta in the early 1980s, told me. McCauley, who was fifteen years younger than Ann and a mother of two small children, remembered once asking Ann for advice about men. “She said, âI'm so sorry, I have no idea. I just have nothing to offer you. I haven't learned anything yet,'” McCauley told me. “She was befuddled by them. They were interesting to her; she had this intense curiosity. Her relationships had not worked out. Like many women, she didn't understand men. She was a cultural anthropologist, it was a kind of

topic

: âInteresting, but don't know!'”

topic

: âInteresting, but don't know!'”

Life in the bubble had its downside for an unmarried American woman with a half-Indonesian daughter at home and a half-African son in college thousands of miles away. In a community made up largely of married men with wives and children at home, Ann was an anomaly. “You're more subject to gossip,” said Mary Zurbuchen, who had become a single parent by the time she returned to Jakarta in 1992 as the Ford Foundation's country representative. “People might have wondered who she was and who she was hanging out with. They might have noticed things.” After attending a meeting of high-ranking Ford people from all over the world, Nancy Peluso remembered, Ann remarked that nearly all the participants were male, and those who were not male were mostly unmarried or childless. “She was really the odd person out,” Peluso said. Ann's home life “imposed different kinds of constraints on her life that Ford was simply not cut out to understand.”

Suzanne Siskel, who joined the Ford Foundation as a program officer in Jakarta in 1990, ran into Ann at a party in 1990 shortly after accepting the job. “She looked at me,” Siskel told me. “She said, â

Hmm.

You're going to work for Ford? Get ready for the eighteen-hour workday.'”

Hmm.

You're going to work for Ford? Get ready for the eighteen-hour workday.'”

The logistics of managing Ann's household could be complex: “Barry will stay in Indonesia +/- one month and then return to New York via Honolulu, taking Maya with him and dropping her off at her grandparents for the rest of the summer,” Ann wrote to her boss, Tom Kessinger, in April 1983, laying out the family's travel plans for the summer after Barry's college graduation. “This will count as her home leave. I will either go to Hawaii at the end of the summer to pick her up, staying two weeks as my home leave, or I will have her grandparents put her on a plane to Singapore and I will pick her up there. We will do our physicals in Singapore at that time.” For work, Ann traveled often: New Delhi, Bombay, Bangkok, Cairo, Nairobi, Dhaka, Kuala Lumpur, and throughout much of Indonesia. On at least one occasion, she appealed to Ford to rewrite its spouse travel policy to cover dependent children. “This is particularly relevant for single parents who do not have another responsible adult in the household to handle child care during periods of extensive travel,” she wrote in a memo to New York in December 1983. On the other hand, the cost of living in Jakarta, combined with a Ford salary and benefits, made it possible to be a single mother in a high-powered, travel-intensive job in a way that might have been more difficult in the United States.

“You managed,” Zurbuchen said. Even if barely.

The Jakarta International School, where Ann enrolled Maya, was both extraordinary, in its community and curriculum, and extraordinarily exclusive. Founded by international organizations, such as the Ford Foundation, that put up money in return for shares, it served the families of those institutions. The grounds of the new campus in South Jakarta were landscaped with tropical flowers. There was a swimming pool, air-conditioning, a theater with plush upholstered seats, where students performed plays by the likes of George Bernard Shaw. The faculty was international. The student body comprised fifty-nine nationalities, with the United States and Australia contributing the most. Parents were accomplished and ambitious for their children, and there was an abundance of nonworking mothers available to, say, sew kimonos for a production of

The Mikado.

The school played a powerful and positive role in shaping the worldview of its students. “They came to easily transcend the notion that national identity is the normal referent for looking at people,” Tom Kessinger said of his two sons. “And they found early on that friendships take many different forms, particularly over time.” One group was glaringly absent, however. Under Indonesian law, Indonesian children could not attend. When Kessinger wrote to Ann, telling her that Maya's enrollment had been approved, he added that the only hitch was that the school would need copies of the first page of Maya's passport and of Ann's work permit: “They need them to satisfy Government of Indonesia regulations for all students, and are somewhat concerned because she obviously carries an Indonesian surname.” In that way, among others, the school stood apart. “It was like a satellite on its own,” said Halimah Brugger, an American who taught music there for twenty-five years. Frances Korten, who joined the Ford Foundation office as a program officer in 1983 and had a daughter in Maya's class, recalled, “That kind of insularity of the foreign community was something that Ann, I think, frankly, more than the rest of us, felt was really not good. . . . To have her child going to a school that Indonesians couldn't attend, I think, was an affront.”

The Mikado.

The school played a powerful and positive role in shaping the worldview of its students. “They came to easily transcend the notion that national identity is the normal referent for looking at people,” Tom Kessinger said of his two sons. “And they found early on that friendships take many different forms, particularly over time.” One group was glaringly absent, however. Under Indonesian law, Indonesian children could not attend. When Kessinger wrote to Ann, telling her that Maya's enrollment had been approved, he added that the only hitch was that the school would need copies of the first page of Maya's passport and of Ann's work permit: “They need them to satisfy Government of Indonesia regulations for all students, and are somewhat concerned because she obviously carries an Indonesian surname.” In that way, among others, the school stood apart. “It was like a satellite on its own,” said Halimah Brugger, an American who taught music there for twenty-five years. Frances Korten, who joined the Ford Foundation office as a program officer in 1983 and had a daughter in Maya's class, recalled, “That kind of insularity of the foreign community was something that Ann, I think, frankly, more than the rest of us, felt was really not good. . . . To have her child going to a school that Indonesians couldn't attend, I think, was an affront.”

It was not easy. Ann wanted Maya to have an English-language education, and Maya would have been ill equipped to leap into an Indonesian school for the first time at age ten or eleven. In preparation for entering the Jakarta International School, Ann had made sure that Maya's homeschooling included English. But Maya felt, as she put it, some “discomfort being the only Indonesian in the Jakarta International School.” It was a discomfort of which Ann was surely aware. “I think batik-making was the only Indonesian thing that I did,” Maya remembered. “I remember taking choir and singing âTie a Yellow Ribbon Round the Old Oak Tree.' We did

Pygmalion

and British history.” Hoping to gain acceptance, she brought in photographs of American relatives she did not even know. “There were a couple of mixed kids like me,” she said. “No full-blooded Indonesians, except folks who worked there. Some. I certainly felt like I was in two different worlds: the world of Indonesia that I knew, populated by Indonesians, and then the world of JIS, which was basically an expatriate school.” Ann worried that the nature of her work would affect Maya's shot at social acceptance. “Ann said Maya's friends thought Ann's job was rather oddâgoing into the field, talking with poor people,” Yang Suwan told me. When Maya had friends coming over for the night, Yang recalled, Ann seemed uncharacteristically anxious. The Indonesian snacks would disappear from the dining room table. “Suddenly, there are steaks and soft drinks,” remembered Yang. She would say, teasingly, “Ann, this is not locally made!” Ann also worried about Maya's exposure to the excesses of some of her more privileged, jaded classmates. Richard Holloway remembered Ann observing, in some distress, “I'm afraid that this comes with going to an international school, because most of the kids there have too much money.”

Pygmalion

and British history.” Hoping to gain acceptance, she brought in photographs of American relatives she did not even know. “There were a couple of mixed kids like me,” she said. “No full-blooded Indonesians, except folks who worked there. Some. I certainly felt like I was in two different worlds: the world of Indonesia that I knew, populated by Indonesians, and then the world of JIS, which was basically an expatriate school.” Ann worried that the nature of her work would affect Maya's shot at social acceptance. “Ann said Maya's friends thought Ann's job was rather oddâgoing into the field, talking with poor people,” Yang Suwan told me. When Maya had friends coming over for the night, Yang recalled, Ann seemed uncharacteristically anxious. The Indonesian snacks would disappear from the dining room table. “Suddenly, there are steaks and soft drinks,” remembered Yang. She would say, teasingly, “Ann, this is not locally made!” Ann also worried about Maya's exposure to the excesses of some of her more privileged, jaded classmates. Richard Holloway remembered Ann observing, in some distress, “I'm afraid that this comes with going to an international school, because most of the kids there have too much money.”

Ann wanted Maya, like Barry, to be a serious student. “She hates me to brag, but I am forced to mention that she made high honors this term,” she wrote to Alice Dewey in February 1984. She made her expectations clear. “Ann was pretty strict with her,” Rens Heringa remembered. “I think she needed to be. Maya was too pretty for her own good. Ann talked to her, took her to taskâto do her homework, to be a serious student, to not do the things that many of her classmates did.” She worked hard to pass on her values. On one occasion, she arranged for Maya to accompany a friend of Ann's who was doing research in a slum area of Jakarta, then was upset when the colleague's methods fell short of Ann's exacting standards. Ann herself took Maya into the field and traveled extensively with her outside the country. In April 1984, Ann used her annual home-leave allowance instead for what she called a “grand tour” with Maya to Thailand, Bangladesh, India, and Nepal. “I had to spend five days en route at an employment conference in Dhaka, but the rest was vacation and great fun, despite beastly dry season weather and dust storms in North India,” she wrote to Dewey late that month. “Saw lots of Moghul palaces and forts, rode elephants, rode camels, bought heaps of silk and clunky silver jewelry and useless gew-gaws very cheapâaltogether a most satisfying trip.”

Ten months earlier, Ann and Maya and a group of Ann's friends had traveled to Bandungan, a hill resort near Semarang in Indonesia, to watch a total solar eclipse over Central Java. The government had campaigned for weeks to convince Indonesians to stay inside with their windows covered in order to avoid being blinded by the sight of the eclipse. The countryside was eerily empty, many Javanese having taken to their beds in fear. The group drove past mosques packed with men, all turned toward the interior, praying. From Bandungan, they made their way to a place where nine small eighth- and ninth-century Hindu temples sit one thousand meters up in the foothills of Gunung Ungaran. Reached by a trail through a ravine and past hot sulfur springs, the place offered one of the most dazzling views in Java, to the volcanoes in the distance. “We sat on the edge of the escarpment and watched the shadow of the eclipse rushing across the plain beneath us and engulfing us,” recalled Richard Holloway, who had gone along on that trip. The horizon turned red, according to a later description, “and in the half-light distant volcanoes usually obscured by the glare of the sun became visible. For the four minutes of total eclipse, the sun, almost directly overhead, looked like a black ball surrounded by a brilliant white light.”

Ann remained in regular contact with Maya's father, Lolo. They spoke often by phone and met for lunch, according to Paschetta Sarmidi, the secretary who worked with Ann. “They tried to take care of Maya together,” Sarmidi said. But Lolo's second marriage had changed Maya's relationship with his family. His new wife was young and “not secure enough to bring me into the familyâand certainly not Mom,” Maya said. “We stopped going to all family functions. There was a complete loss of contact.” Maya continued to see her father on his own, but he never took her to see his family or play with her cousins. Ann complained to at least one friend that Lolo, like a stereotype of a divorced parent, was lavishing Maya with luxuries, toys, and sweets. “That particular thing really irritated her,” her old friend Kay Ikranagara remembered. “She felt that he had grown up without material things, and now he put so much importance on material things. He was conveying this to Maya.”

Other books

Hotel Florida: Truth, Love, and Death in the Spanish Civil War by Amanda Vaill

Give Us a Chance by Allie Everhart

Murder Ring (A DI Geraldine Steel Mystery) by Leigh Russell

The Year My Life Broke by John Marsden

Emerald Windows by Terri Blackstock

The Hunger by Eckford, Janet

Coffee, Tea, or Murder? by Jessica Fletcher

Emerging Legacy by Doranna Durgin

Deadly Honeymoon (Hardy Brothers Security Book 7) by Hart, Lily Harper

Pay Dirt by Garry Disher