A Teardrop on the Cheek of Time: The Story of the Taj Mahal (33 page)

Read A Teardrop on the Cheek of Time: The Story of the Taj Mahal Online

Authors: Michael Preston Diana Preston

Tags: #History, #India, #Architecture

By 1643, the year that the main tomb complex was completed, the Taj’s gardens were yet to reach their full maturity but were already stocked with bright, fragrant flowers and luxuriant trees. They were, in the words of Shah Jahan’s historian Salih, like

‘the black mole on the forehead of all the world’s pleasure spots and each of its bounty-laced flowerbeds is pleasing and heart-captivating like the flowerbeds of the garden of the keeper of Paradise. Its attractive green trees are perennially fed with the water of life and the stature of each … surpasses that of the celestial lotus tree … light-sprinkling fountains gush forth sprinkling pearls of water … In short, the excellent features of this paradise-like garden such as its pathways fashioned entirely of red stone, its galaxy-indicating water channel and its tank of novel design which has materialised from the crystal of purity from the world of illumination have reached a stage surpassing imagination, and the smallest particle of its description cannot be accommodated by the faculty of speech.’

*

Some architectural historians argue that the positioning of ablution tanks in mosques may, in turn, originate from the placing of fire pits in Zoroastrian temples, from which many early mosques in Persia were converted.

*

Amid all their opulence and prodigality, the Moghuls showed some economic prudence when they sold excess fruit and flowers from their imperial gardens, including the Taj Mahal, to offset their running costs.

12

The Illumined Tomb

O

n the night of 6 February 1643, Shah Jahan mourned his dead wife in the luminous tomb he had created for her. It was almost complete, although embellishments would continue until 1648 and subsidiary parts of the complex would not be finished until around 1653. The occasion was the twelfth

urs

, or ‘death anniversary’ – the first time the ceremonial feast had been held in the Taj itself.

*

The back of the earth-supporting bull sways to its belly,

Reduced to a footprint from carrying such a burden

.

Light sparkles from within its pure stones

,

Like wine within a crystal goblet

.

When reflections from the stars fall on its marble,

The entire edifice resembles a festival of lamps

The mourners passed through the great portal on the south side of the mausoleum, framed by Amanat Khan’s fluid calligraphy, and through a grilled door into the central octagonal chamber. The marble floors were carpeted with richly coloured rugs of intricate design and the walls were hung with costly velvets and silks gleaming in the soft light from enamelled golden chandeliers – during the

urs

ceremonies tombs were especially illuminated as emblems of the

‘shining excellencies and perfections’

of the departed. Mullahs chanted prayers

‘for the repose of the soul of Mumtaz residing in the gardens of Paradise’

, the sound rising and echoing in the void beneath the dome.

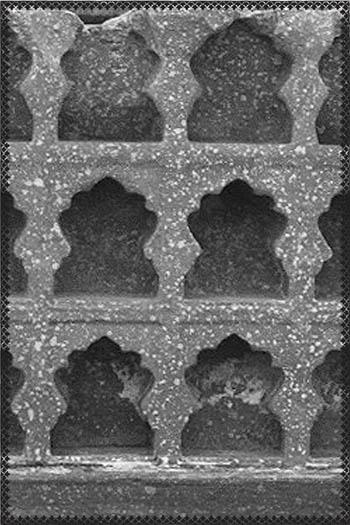

In the centre of the chamber was an octagonal latticed marble screen over six feet high,

‘highly polished and pure … with an entrance fashioned of jasper after the Turkish fashion, joined with gilded fasteners’

, according to the court chronicler Lahori. The screen, or

jali

, was a replacement for the bejewelled solid gold rail Shah Jahan had originally commissioned but which he ordered to be removed for fear of thieves and vandals. Carved from a single block of marble to resemble filigree, the screen veiled the slender white marble cenotaph within. This cenotaph, inlaid with bright jewelled flowers, their curving fronds suggesting vitality and renewal as if they were truly growing over the marble, lay directly beneath the dome. The top and sides of the cenotaph bore gracefully swirling Koranic inscriptions, and an epitaph inlaid in black marble at the southern end told the onlooker that here was: ‘The illumined grave of Arjumand Banu Begam, entitled Mumtaz Mahal, who died in the year 1040’.

Mourners that night probably also saw the fabulous ‘sheet of pearls’ which, according to one of his historians,

‘Shah Jahan had caused to be made for the tomb of Mumtaz Mahal, and which was spread over it upon the anniversary and on Friday nights’

. Directly beneath, in the crypt, a second white marble cenotaph containing Mumtaz’s body rested on a marble platform. It was as lavishly inlaid and bore the same epitaph to Arjumand Banu, but its inscriptions also included the ninety-nine Islamic names for God.

The chief mourner, Shah Jahan, probably reached the Taj by boat from the Agra fort. However he journeyed there, that first marking of Mumtaz’s death in the Taj itself must have seemed particularly charged with meaning. As well as reviving tender memories, it marked a crucial stage in the achievement of his ambition – the creation of a perfect, Paradise-resembling tomb as Mumtaz’s final resting place.

The realization of that ambition had not been cheap. No complete, detailed accounts have survived whose authenticity is above question. Shah Jahan’s historian Lahori recorded the cost of constructing the Taj to be ‘fifty lakhs’ of rupees – 5,000,000 rupees. However, this number is thought to have covered only direct labour costs and to exclude many items such as materials. Using data from some of the later disputed manuscripts, some historians put the figure as high as 40,000,000 rupees. The construction itself had been funded by the imperial treasury and by the treasury of the province of Agra. Shah Jahan had also ordered a deed of endowment to be drawn up, including the revenue from thirty villages, to ensure that his beloved Taj would be properly maintained and guarded in future years. He intended his great creation to endure. As a court poet eloquently expressed it:

When the hand of perpetuity laid that foundation,

Impermanence ran fearfully to hide in the desert

Shah Jahan’s greatest consolation over the twelve years since Mumtaz’s death had been Jahanara, the oldest surviving child of the fourteen Mumtaz had borne him. As well as filling Mumtaz’s role as first lady of the Moghul Empire, Jahanara had also cared for the younger brothers and sisters, for whose safety and security the dying Mumtaz had pleaded. Like her mother, Jahanara was highly educated, with interests ranging from music and architecture to religion and literature. She knew the Koran by heart, was well versed in Persian and Arabic and had become an accomplished writer. As with her beautiful mother, no formally attributed likeness of her exists, although a portrait in an album prepared for her brother Dara Shukoh in about 1635 may be Jahanara. A graceful young woman rests one hand lightly on the trunk of a pink-blossomed tree, while in her other hand she holds a spray of flowers. Narcissi and lilies bloom at her feet.

Dara Shukoh, only one year her junior, was Jahanara’s favourite brother. He shared her love of Sufism and both had become devotees of the Sufi Mullah Shah. Jahanara wrote that

‘of all the descendants of Timur, only we two, brother and sister, were fortunate enough to attain this felicity. None of our fore-fathers ever trod the path in quest of God and in search of the truth. My happiness knows no bounds, my veneration for Mullah Shah increased and I made him my guide and my spiritual preceptor …’

Jahanara had lovingly made the arrangements for Dara Shukoh’s wedding to his cousin – originally planned by Mumtaz and postponed because of her death – and spent huge sums on the festivities. English traveller Peter Mundy witnessed some amazing pyrotechnics:

‘great elephants whose bellies were full of squibs, crackers, etc; giants with wheels in their hands, then a rank of monsters, then of turrets, then of artificial trees [and other] inventions, all full of rockets …’

For the first time since Mumtaz had died Shah Jahan permitted singing and dancing at court.