A Thousand Sisters (16 page)

Read A Thousand Sisters Online

Authors: Lisa Shannon

“How old is the baby?” I ask her.

“One year, eight months. I didn't think I could accept it. Whenever I saw it, I was only seeing a sign of my bad life.”

I give her a little hug.

She smiles. “I'd like to keep you near me.”

Then Wandolyn starts crying again. “You are the only one who takes care of me and knows about my situation. The money helps me take care of my baby and my children at school.”

“I consider you my friend,” I respond. “I'm happy to do it.”

“I am extremely happy to see you,” she says. “My mom died when I was four. You are my mother. Even my husband is proud of my new mother. My children always say, âWe have a grandmother who takes care of us. We are studying because of our grandmother.' Every day my children ask me to show them your photo. They ask, âCan we see our grandmother someday?'”

A grandmother! I'm only thirty-one!

I'm stunned. A couple of postcards, letters, and photos have given me near mythic status in this family and transformed me into a kind of magic fairy godmother.

Wandolyn continues. “My husband encourages me. He says, âIn the past, you wanted to put an end to your life, but now you've found a mother and that mother helps us. You should be happy.'”

I ask her, “You wanted to end your life?”

She looks me in the eye and says quietly,

“Ndiyo.”

Yes.

“Ndiyo.”

Yes.

There is no way I can live up to the impossibly personal role that Wandolyn has cast for me. But there is also no way I can dismiss her at the end of this meeting, after only a ten-minute exchange. She has staked her claim.

Despite Women for Women HQ's warnings that these visits only cause problems, I cannot leave without meeting my sweet little “grandchildren.”

Wandolyn's son greets us as we emerge from the car on the outskirts of Walungu. He shakes my hand shyly. I follow Wandolyn up a long, winding path through the rural countryside, past banana trees, and pigs and calves munching on underbrush, to her home compoundâa perfectly round African straw hut.

If I had dreamed this scene a few years ago, how absurd it would have seemed! Me, meeting my half-grown African grandchildren in their tribal compound, something straight out of a storybook but tense with the weight of war around us. I would have woken up and thought it impossibly bizarre.

The turns life can take.

I announce, “Grandma's here!” and embrace each of the children. Wandolyn's husband is fourteen years older than she is and he is frail, clearly in bad health. He shakes my hand with a gentle formality. I peek inside their dark hut. Scrawny white rabbits stumble around in the dark like ghosts.

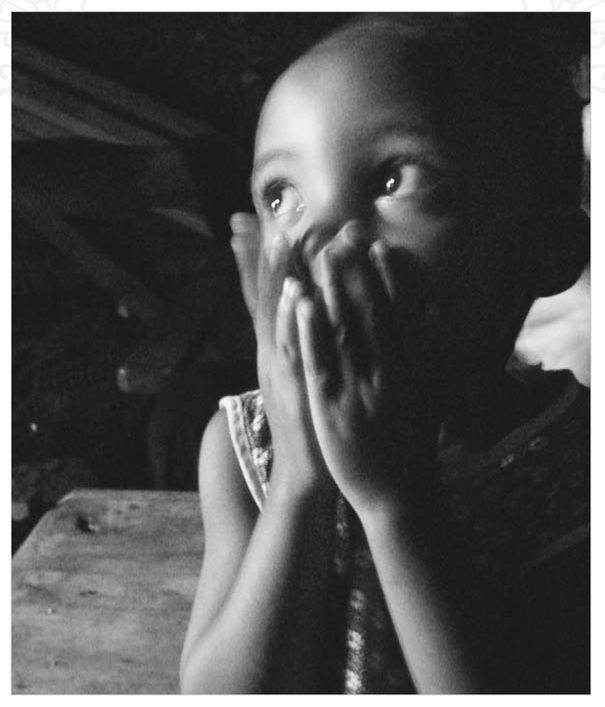

Wandolyn holds her baby daughter, Nshobole, who is a stoic child. But little ones are often shy around new people, so it's hard to measure the impact of the event on her psyche. “May I hold her?”

I take her in my arms, searching her eyes for evidence.

Neighbors gather, and I know that can mean trouble after I have gone. It starts to rain and it's best not to stay, so I say goodbye.

Yet it isn't enough. Not nearly enough. I ask Wandolyn, “When can I meet you again?”

A few days later, we meet at the program center in Walungu. Her neighborhood has been abuzz with my visit. They're saying I've come to take her family to America. Demands for money are sure to follow.

Wandolyn brings Nshobole with her. The baby sits on my lap while her mom talks.

“I was coming from fetching water in the valley when I heard gunshots,” Wandolyn says. “When I got home, men were in the compound. They were

Congolese, speaking a local dialect. My husband had been at home with my kids, but they hid on the farm. Tutsi soldiers had invaded Bukavu and Congolese government soldiers retreated here to Walungu.

Congolese, speaking a local dialect. My husband had been at home with my kids, but they hid on the farm. Tutsi soldiers had invaded Bukavu and Congolese government soldiers retreated here to Walungu.

“I tried to escape, to run, but they caught me and told me to go in the hut. I asked them to enter the house and take what they pleased instead of taking me. They said they would take rabbits and the cassava flour I had just gotten from the mill. They didn't. They said, âFrom you, we need only yourself.'

“The commander told me to lay down.

“I said, âI don't need to do that.'

“They threw me down and began cutting me. They slapped my ears, so I couldn't hear. They stabbed one of my buttocks. It was so painful, I cried. They laughed at me and told me they would kill me.”

Wandolyn spaces out, rocking; her breathing is labored. Hortense says, “She's having emotional flashbacks from reviewing what happened to her. It's as if this is the first time she has told the story.”

“They laid me down and started to rape me. They used a piece of cloth to wipe. When one finished, he wiped with the same cloth. Then the other would introduce himself. When I cried, they said stabbing my buttocks was nothing compared to what they would do. They told me they would stab me in the neck, they would kill me. I felt dying was better than suffering like this. There were so many, but while I was conscious I only saw three. I lost consciousness.” She folds over, collapsing her head and hands on her knees, crying.

I approach and hug her, interrupting. “You don't have to talk.”

She sits up and continues, seemingly determined to get it out. “They folded the cloth and passed it, wiping.”

In my best attempt to usher her through the story, I ask, “Did your husband know about what happened?”

“When he came back, he found they had split my legs. I was lying in pain. He knew because he was the one who treated the injury. When I started to tell him, my husband said, âKeep quiet. Don't say more. Don't tell to anybody. ' He kept silent.

“It was June. I hid myself until December. I wouldn't go out. Only my children did housework, went to farm. As days went by, I felt woozy. I would fall down because of the level of infection. My husband pushed me to go to the hospital. I was ashamed to go to the doctor, because it was taboo to speak about rape. After six months, I accepted to go to hospital because my wounds were so infected that flies were getting in the house everywhere.

“The doctor was angry to see they kept me at home so long. The infection was high. A nun stayed close to me, to take care and wash me.

“The day the doctor told me I was pregnant, I felt dying was better than remaining with that pregnancy. When I went into labor, I was revolted.

“I delivered a baby girl. They brought the baby to me. The nun counseled me, âThe baby is innocent, the baby needs love.'

“I said, âKeep it away.' I didn't even like to hear about that baby. I didn't even like to see that baby. I considered it the source of my misery and suffering. I said, âI won't even look at that baby.'

“The next day, the nun asked me to breast-feed. I said there was nothing inside.

“They had to ask other women in maternity to give the baby some milk. After two months, the doctors told me they were tired of asking for milk. They asked me to take the baby. I said no.

“I was worried about my husband, who was sick, who I had been looking after. I was the only one looking after my kids. Now they were suffering from malnutrition because I was in the hospital. The doctor promised to take care of my husband and me.

“The nun sent for my husband. She told him I delivered a baby girl. When my husband heard, he said, âYou are not guilty. I won't say anything against the baby.' My husband told me to take the baby, because it was a gift from God to us, even if it came from suffering and pain. That's how she got her name, Nshobole, which means âGift from God.'

“My husband was suffering malnutrition; he couldn't walk. But the doctor took care of him. He started standing up. I regained hope, little by little.

“My husband developed a friendship with the doctor. My husband told them we would take the baby home, but we didn't have the means. The nun told me I would only have to help with breastfeeding, but on all the other counts she could be responsible. They even gave me baby clothes. Everything for the baby came with us when we left the hospital.

“I was careless with the baby. I left the baby to the father. When I had babies before, he wouldn't touch them. He said he didn't know how to take care of them, but this one, he was taking it each time she cried. Of my children, that was the one my husband loved the most. He couldn't accept the baby crying.

“My husband loves me so much. He is sad when he finds me unhappy. He said he would never separate with his wife. But even if I were to be infected [with HIV], he would rather be infected with me so we can die together or live. He said only death will separate us.”

“How do you feel about your husband?” I ask her.

“I love him so much,” Wandolyn says. “When I'm angry and I quarrel with my husband, he keeps quiet and asks me to cool down. He never speaks when I'm angry. He is grateful because I suffered in order to take care of him, and I didn't tell anyone we were living separate lives because of his health.” “How do you feel about the baby?” I say.

“He loved the baby so much. He tells me the baby is my own blood and I have no right not to love the baby. He was even angry because I told the doctor the baby is not his. He needed me to tell everyone it is his. With his support, I love the baby, because I love him so much. Even today, he never once speaks about the event that led to the baby. I didn't choose to have this baby, but the baby is mine. The baby is the profit of our misfortune.”

Hortense says, “You must give her something to care for the child.”

It's not a suggestion. It's mandatory. I scrounge around my bag and pull out US$40, slipping it to Wandolyn with the uneasy feeling I've just paid her to relive all that.

Wandolyn's husband joins us later. I speak to him privately and ask him about the event. “How did you feel when Wandolyn came home with injuries?”

“I prayed to God for her to heal,” he says. “My father advised me to take another woman, but I said it won't be possible.” He wags his finger. “I made a vow to live with her in good and evil, only death would separate us.”

“What would you say to men who want to reject their wives?” I ask.

“I can advise them about mutual forgiveness, show them it didn't happen willingly,” he says. “We were faithful; we were living a Christian life. That's when the event happened. I kept it a secret. I wouldn't reject her because we were faithful to each other. We have mutual acceptance. We share everything. She loves me. She hides me nothing. She respects me. And I feel she makes me happy.”

Wandolyn and I sit outside a church compound, in the shade under some trees. Nshobole perches on her mom's knee. I snap a photo. The mother, with her child, looks like a living religious icon. An African Madonna.

I give the baby a sheet of sparkly heart stickers. The little girl is mesmerized. Wandolyn peels off stickers and sticks them on Nshobole's wrists and arms. Nshobole pulls one off, then she reaches back and sticks the sparkly heart on her mother's cheek.

CHAPTER SIXTEEN

Generose

OF ALL MY

sisters in Congo, the one I've most been looking forward to meeting is Generose. Her letter describing the way her leg was cut off, though it was only a brief sketch, was the most awful incident any sister had written about. Her photo intimidates me, for sureâshe looks so shell-shocked, even angry. But I felt we were working as a tag team when her letter helped me lobby.

sisters in Congo, the one I've most been looking forward to meeting is Generose. Her letter describing the way her leg was cut off, though it was only a brief sketch, was the most awful incident any sister had written about. Her photo intimidates me, for sureâshe looks so shell-shocked, even angry. But I felt we were working as a tag team when her letter helped me lobby.

Our meeting was scheduled for this morning. She didn't show.

Â

I'VE SPENT ALL MORNING on the veranda at the Women for Women ceramics studio, lazily sipping soda in the shade with the other twelve sisters in her group. I watch them all walk away together under the trees, laughing and chatting. They look a little fatter, dress a little smarter and smile a little wider than most Congolese women I see around Bukavu. We've had a lovely time, but as they glance back and I wave goodbye, I'm trying to conceal my disappointment that Generose was not among them.

One sister lingers, sick with what she believes is malaria. We drive her to the neighboring Panzi Hospital to get checked out. Doctors shortly confirm that this young, unmarried woman's “malaria” is actually a pregnancy.

On the way out of the hospital in the parking lot, I work overtime with a pep talk: “My American sister is a single mom. It happens all the time. I've met so many Congolese single mothers who thrive all on their own. . . .”

As we are saying goodbye, someone calls my name.

I look up. A woman on crutches approaches me, smiling warmly and wearing a traditional dress under a Puma sports jacket. She says, “I am your sister. I am Generose.”

I look closely at her. She's much heavierâand happierâthan she looks in her photo. But it is her!

Other books

Awakened (Vampire Awakenings) by Davies, Brenda K.

The Dark City by Catherine Fisher

Christmas at Jimmie's Children's Unit by Meredith Webber

The Sultan's Choice by Abby Green

Death of a Teacher by Lis Howell

Gabriella - Alpha Marked, Book II by Celia Kyle

Horus and the Curse of Everlasting Regret by Hannah Voskuil

That Old Flame of Mine by J. J. Cook

Death Takes a Honeymoon by Deborah Donnelly

45 - Ghost Camp by R.L. Stine - (ebook by Undead)