A Very Unusual Air War (2 page)

Read A Very Unusual Air War Online

Authors: Gill Griffin

This was the man who held air speed records, setting a straight and level speed of 455mph in a Mustang, which made it the fastest operational airplane in the world at the time (see the entries for 5th March 1943 and 28th January 1944). He also made the first flight of a Spitfire as a fighter-bomber on 30th November 1942. Then, in late 1944 and early 1945 he was involved in the early operational testing of

the Gloster Meteor Mk III, so his flying extended into the jet age. He always talked of himself as a ‘hack’ pilot, an ordinary Joe. Perhaps his lack of a medal left him with a feeling that he had done nothing special. He was always happy to talk about his time in the Royal Air Force but it was more to tell you about the aircraft and the people he had met than about himself.

Herbert Leonard ‘Len’ Thorne always denied being a Battle of Britain pilot. In British military eyes the ‘Battle’ started at the end of July 1940 and was over at the end of October 1940. He gained his ‘wings’ on his 21st birthday, 13th April 1941, went to the Operational Training Unit at Hawarden and was then posted to 41 Squadron, a front-line fighter squadron, starting active service on 11th June 1941. He always maintained that he missed being ‘one of the Few’ by six months. However, the Luftwaffe was still making bombing raids and by the end of June the RAF was sending attacking sweeps over occupied France and Belgium. The life of a fighter pilot was still measured in minutes in the air.

He flew and was friends with many of the top ‘aces’ of the war and his personal memories of these heroes add to our historical knowledge. Among others he talks about are Al Deere, Brendan ‘Paddy’ Finucane, T.S. ‘Wimpy’ Wade and James ‘One Armed Mac’ MacLachlan. He explains air combat tactics clearly. He describes technical details of the aeroplanes coherently and his lifelong love of those beautiful machines and of flying shines through.

This is the story, told through the medium of his pilot’s logbook, of a man who so loved flying that, after making a full recovery from a cancer operation six months earlier, he performed an aerobatic display to celebrate his eightieth birthday.

This was no ‘hack’ pilot. He was an extraordinary one.

* * *

After his time in the RAF, Len returned to work for High Duty Alloys in Slough and Redditch. He later moved into rivet manufacturing with Pearson and Beck, a local Redditch factory. He moved on to Black and Luff, which became a subsidiary of Bifurcated and Tubular Rivet Company of Aylesbury, rising to the position of executive Managing Director of the Midland Division of that company.

He became a Freemason in Slough in 1948, being initiated into Industria Lodge No. 5421 and when he moved permanently to Redditch he joined a local Lodge, Ipsley Lodge No. 6491 in the Province of Warwickshire. He was also a member of Bordesley Abbey R.A. Chapter No. 4495, meeting in Redditch and in the Province of Worcestershire. He remained a Freemason for the rest of his life. He died just before he was due to receive his 60 Years Certificate.

He was a member and Past President of the Redditch Probus Club and delighted in telling anyone who would listen that his very ‘correct’ wife Estelle liked to explain the acronym as ‘Poor Retired Old B***s Useless for Sex’. Len and his wife were also active members of the League of Friends of the Alexandra Hospital in Redditch. They worked together in the coffee shop for many years until Estelle

became ill. Following her death in 1997 Len continued for a short time in the coffee shop, now working with his daughter Gill. He was also a member of the Committee and edited the League’s quarterly newsletter.

He was a very gregarious man and was a member of the Bromsgrove branch of The Royal British Legion. He joined the Stratford branch of The Air Crew Association and became President and he was a life member of the Spitfire Society. For several years he was Chairman of the civilian committee of Studley ATC, 480 Squadron.

Len died on 6th June 2008 – D-Day. His interest in and love of flying never died. In his last letter, to the chairman of the local Spitfire Society, four days before he died, he wrote ‘My interest in the Spitfire will never wane.’

Like many other pilots and ex-pilots, Len Thorne was deeply moved by this poem. He had a copy of it on a bronze plaque in his lounge.

High Flight (An Airman’s Ecstasy)

Oh! I have slipped the surly bonds of earth

And danced the skies on laughter-silvered wings;

Sunward I’ve climbed, and joined the tumbling mirth

Of sun-split clouds – and done a hundred things

You have not dreamed of – wheeled and soared and swung

High in the sunlit silence. Hov’ring there

I’ve chased the shouting wind along, and flung

My eager craft through footless halls of air…

Up, up the long delirious, burning blue,

I’ve topped the windswept heights with easy grace

Where never lark, or even eagle flew –

And, while with silent lifting mind I’ve trod

The high untrespassed sanctity of space,

Put out my hand and touched the face of God.

Pilot Officer Gillespie Magee

No. 412 squadron, RCAF.

Killed 11 December 1941

I was born on 13th April 1920 in the village of Waddesdon, Buckinghamshire, the fifth child born to Benjamin and Lydia Thorne. My sister Doris was fifteen years my senior, my brother Leslie thirteen years older and Gwen ten years older. My other sister, Sybil, died in infancy. I attended the C. of E. school in the village. Waddesdon is the site of Waddesdon Manor, a Rothschild home, now part of The National Trust. Mother and father were the landlords of The Five Arrows Hotel in Waddesdon. Sadly, my father Benjamin Thomas Thorne had died in 1927 and three years later my mother married a Birmingham man, Ernest Massey.

In 1931, having passed a scholarship, I moved to Aylesbury Grammar School. After Father’s death my stepfather Ernest helped my mother with the hotel and garage business but in the year I started at grammar school, his health, too, became a problem and they were forced to give up the hotel and also the garage business which had been started by my father before the First World War. They moved to Birmingham. I remained at Waddesdon for the remainder of my year at Aylesbury, living with my ‘second mother’, Auntie Betty, one of my mother’s younger sisters. At the end of that year I moved to Birmingham and for a brief six weeks attended Saltley Secondary School. In late September 1932, further deterioration in my stepfather’s condition caused another move to Tewkesbury and I became a pupil at Tewkesbury Grammar School, where I spent two happy years. In the summer of 1934 my stepfather died, leaving mother in a very poor condition both financially and in health. It was decided that she would go to live with my younger sister Gwen at Poletrees Farm and for a time there was a strong possibility that, like my stepbrother, Gordon Massey, I would go into the Licensed Victuallers School, a type of orphanage, at Slough. My elder sister Doris, married to Percy Climer, a policeman, refused to accept this and I went to live with them and spent my final two grammar school years at Slough Secondary School. In 1936, having passed the Oxford School Certificate examination, I went to work as a junior clerk at High Duty Alloys, at the main factory on Slough Trading Estate and in 1938, I moved to the newly built shadow factory at Redditch.

I volunteered for aircrew training on Sept. 6th 1939 at the recruiting centre in Dale End, Birmingham. Because I was employed by High Duty Alloys Ltd., a company heavily engaged in production of aircraft components, I was deferred

for three months. I was called to Cardington in January 1940 for medical and educational tests and accepted for pilot training as a cadet, rank AC 2. I again returned to Redditch, to await final call up. This came in May 1940 and summoned me to the receiving wing at Babbacombe in Devon.

Three weeks later I moved to No. 3 ITW at Torquay. With forty-nine others, I was billeted in the White House Hotel, situated high up the bank at the end of the harbour. During our stay we experienced some enemy bombing but suffered no damage. During the raids, mostly at night, we had to go down into the cellars; these cellars still contained an excellent store of wines but to our disappointment all were behind locked grills and remained untouched. My memory of ITW is of much polishing of buttons and buckles and much blancoing of webbing and, on evenings off, drinking Devonshire rough cider, all we could afford. Our officers and NCO instructors were a fine and efficient bunch of men, with whom we got on well. The WO in overall charge of 3 ITW was a super-efficient NCO who, we understood, had been transferred from the army. I remember his name as Warrant Officer Edsal, a much-feared disciplinarian who was not popular. Of course we were viewed as objects of interest and, dare I say, admiration, by the young ladies of Torquay. I expect the uniform had something to do with the attraction. Naturally, we took advantage of this whenever possible and I remember a pretty little girl who worked in the big store, Bobby’s, in the High Street. It was strongly rumoured that to discourage our amorous activities, our tea was laced with bromide or some such chemical. If this was true it did not work on me!

After successful completion of the ITW course towards the end of September 1940, at the height of the Battle of Britain, I was posted to No. 7 EFTS (Elementary

Flying Training School) at Desford near Leicester, where I would be taught to fly the DH 82, De Havilland Tiger Moth, a small biplane training aircraft.

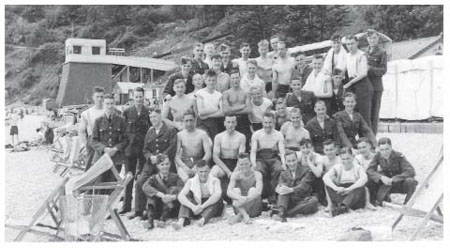

Pilots under training outside the Norfolk Hotel, Torquay, 1941. Len Thorne far left.

Pre-war, Desford had been a rather expensive private flying club owned by Reid and Sigrist, the instrument makers. At the end of 1939 it was taken over by the Air Ministry. The civilian flying instructors were ‘invited’ to stay on and those who did so were commissioned into the RAF. The school facilities were palatial, with a central block of buildings housing a large lounge with an adjoining dining room and kitchens. We cadets were treated like young gentlemen: pre-war habits had not yet died out. We had our own rooms in the nearby living quarters and even a batman to every four cadets.

A small number of the boys on this course were from wealthy backgrounds and had university or public school educations. These chaps were destined to become commissioned officers if they successfully completed the flying courses. The majority, like myself, were grammar school boys. To us, after the bare rooms of commandeered hotels at Torquay, Desford was pure luxury. Having entered the service as AC2s (Aircraftsman Second Class), popularly referred to as the lowest form of animal life in the Air Force, those of us who had passed the physical and ground training examinations were promoted to LAC (Leading Aircraftsman).

For the first few weeks there was no great sense of urgency and things moved at a leisurely pace. Our days were spent partly in flying and studying the Tiger Moth and partly in lessons and lectures. The latter included the theory of flight, aircraft engineering, Morse code signalling using an Aldis lamp or buzzer, navigation, meteorology and Air Force law. We studied engine starting procedure and safety precautions. Most light aircraft were started by swinging the propeller by hand. First

the engine was turned over in reverse (blow out), then turned over (suck in) with the magneto switches turned off, to draw fuel into the cylinders. Then, the pilot having shouted ‘contact’, the prop was pulled over sharply and hopefully the engine would start. In the event of a non-start, the pilot would shout ‘switches off’ and raise both arms to indicate that it was safe to proceed with a re-start. I well remember being told to keep a large spanner handy as the magneto contacts sometimes stuck but a sharp tap with the spanner would cause them to part. I passed the course with the rating ‘average’.