A Very Unusual Air War (45 page)

Read A Very Unusual Air War Online

Authors: Gill Griffin

I was going through a bad time, worried about the future and stale from 4½ years of flying. In the absence of a commanding officer, O/C Flying (Wimpy) had already gone to become chief test pilot at Hawkers, Langley and with so many pilots returning from the hard fighting in Germany, I had many extra duties with which to cope. I received much help from the adjutant, F/Lt Simms and his staff but towards the end of April I asked for a transfer to other non-flying duties. For the rest of the month and until early July I was appointed range instructing officer at the bombing and firing ranges between Bracklesham and Selsey Bill. I still paid regular visits to Tangmere in my now nominal position of Flight Commander. I did several days as Duty Officer and, surprisingly, I was appointed Officer for the Defence at a Court Martial.

Aircraft parked overnight had locking toggles placed to prevent wind damage to the control surfaces, i.e. ailerons, rudder and tail plane; these had to be removed before flying. The Court Martial followed a fatal accident involving two Typhoons. The first had taken off and, the pilot realising something was wrong with the controls, immediately managed to go round for an emergency landing. Meanwhile a second Tiffie had taken up position ready for take-off and the first plane landed on it, killing both pilots. The station’s senior engineering officer, a wing commander, was held responsible and charged with negligence. He could have had a civilian defence counsel but elected to take his chances with me. He was found guilty but got off lightly with an admonishment, so perhaps I did some good.

So, from mid-April to July I became range instructing officer, telling senior officers of the Fighter Leaders School what they were doing wrong when carrying out ground attacks. In dive bombing it was essential, in order to achieve reasonable accuracy, to dive at or near 70° and this took a lot of determination and practice.

Fortunately I did not know the rank of any particular officer and they did not know that they were being bawled out by a mere Flight Lieutenant. The range control tower was a 60-ft-high open scaffolding tower with facilities such as radio, sight screens and plotting at different levels. The control room was on the top platform and you got there by open ladders from level to level. It was some weeks before I overcame my fear of heights and being shamed by the ground staff boys before I made the climb with my eyes open.

From our bungalow in Bracklesham Bay there were two routes to the range control tower. The first was by road, a long way round through Earnley and including some tortuous lanes, back to the farm where the tower was situated. An easier and nearer way was by foot and bicycle along a path which followed the coast, a distance of about two miles. Near the control tower a tidal brook ran inland but it could be crossed by a plank bridge about 15 inches wide. I usually used my bike and did not dismount for the plank but just gave the handlebars a lift and sailed straight across. One morning the handlebars pulled out and I went sideways into the very stagnant and weed-filled brook. I rescued the bicycle and went on to the farm, looking like the old man of the sea and stinking worse than the farm dung heap. When the lads at the tower could stop laughing, they hosed me down under the farm pump while one of them went by road in the Jeep to collect my No. 2 uniform. Luckily no one had a camera handy, so my mishap was never recorded on film and was known only to the control tower staff and Estelle.

The Jeep is another story. The range not only had orthodox flat and angled targets but also had lines of vehicles arranged nose to tail to imitate an enemy convoy. Crashed vehicles – cars, pickups and lorries – which were damaged beyond repair, were brought from all over the country on ‘Queen Marys’, low loading vehicles. Usable equipment such as batteries was salvaged and fuel and oil was supposed to be drained from tanks and engines. The vehicles were placed on the range as targets for ground attack. It happened that one of the range officers was a skilled car mechanic and he rescued a Jeep that was not too badly damaged. With spares from other machines he rebuilt the Jeep to provide the boys with unrecorded and unlicensed transport to get around the lanes to country pubs. Petrol, which was strictly rationed, was always to be found in newly delivered, written-off transport.

The range extended along the coast for some two or three miles and inland from the beaches for about 1½ miles. It was, of course, strictly out of bounds to all civilians and unauthorised service personnel. I always thought that wild mushrooms were only a late summer or autumn crop but some fertile areas of the range abounded with them that spring. We used to take square sheets of balloon fabric, of which the targets were made, and fill them in the early morning before flying commenced with newly gathered mushrooms. Our local pub, the Bracklesham Bay Hotel, was always good for a bottle of whisky or gin in return for a large bag of mushrooms.

Meanwhile the ranges were being extensively used. Although the Germans had been defeated, the Japanese were still fighting with their usual fanaticism. It was vital to keep up the pressure on land where General Slim and his ‘forgotten’ army were pushing the Japanese out of the Malayan peninsula. Likewise, the Americans and some units of the Royal Navy were island-hopping towards Japan. The pilots at the Fighter Leaders School were trained to the highest possible standard of bombing, gunfire, rockets and napalm dropping before being posted to the Far East. Inevitably, there were a number of accidents and particular care was necessary when using Typhoons and Tempests for dive-bombing. These aircraft accelerated quickly to speeds in excess of 500 mph and it was vital to effect the recovery from the dive in good time with height to spare. I well remember with sadness the one fatal accident that I witnessed; I believe the aircraft was a Typhoon. The pilot left it too late to pull out of the dive and went straight into the ground. He was, of course, killed and all efforts to recover the aircraft failed because it continued to sink into the sandy foreshore faster than a digger could dig down.

The spring that year (1945) gave us some very good, warm weather. Baby Gill loved the beach but needed careful watching as she was apt to run straight into the sea fully dressed! We were very popular with family and friends and our spare bedroom was in constant demand. For most it was their first seaside holiday for six or more years. Among our visitors was Mrs Simms, the adjutant’s wife. I made frequent trips to Tangmere to work with ‘Simmy’ in the affairs of AFDS but in truth he and Peggy Snashall did most of the work. I sometimes put in an appearance at the FLS debriefing but was careful not to let them know what my function was at the range. It was an interesting experience, which I thoroughly enjoyed.

Estelle and I paid weekly visits to Selsey village and got to know the brave fishermen who went out to gather the fruits of the sea, particularly shellfish. The shellfish were kept alive until the day of the week when crabs and lobsters were cooked, ready for delivery to the markets in Chichester. I had a standing order for these items, for delivery to the Tangmere Officers’ Mess and for one or two of the officers who lived out. Among them was Wing Commander ‘Razz’ Berry, who I came to know very well. On one of the Selsey trips I went on a no-cooking day and so bought half a dozen live and very lively crabs in a wooden box, which I placed in the annex of the bungalow while I boiled a large pot of water. Unfortunately, the crabs got loose and were running around happily. In my frantic efforts to catch them I was lucky not to lose one or two fingers!

I made friends with Mr Dormer, who opened his small butcher’s shop in East Wittering on two days a week. We did quite well for meat, which, of course, was strictly rationed. More mushrooms and an occasional petrol coupon worked wonders! Friday was a special day. Estelle walked to West Wittering to the baker’s shop, to collect her allowance of the finest jam doughnuts I ever tasted. Each member of the family was allowed just four each week.

By and large I really enjoyed this interlude in my service but it could not last. At the end of June a professional instructor was posted in and I returned to AFDS normal duties. I still spent most of the time with administration, with just one flight on June 30th in my favourite plane, the Mk IX Spitfire, No.JL356. I spent 50 minutes firing rocket projectiles.

On July 9th I made a 25-minute local flight in a Meteor III, No. EE243, then on the 12th I made a 1 hour, 10 minute flight in an Auster, taking as my passenger Lieutenant Colonel Sanderson, our next-door-neighbour at Bracklesham, a retired army officer and a gentleman of the old school. I gave him a trip round the locality, which he thoroughly enjoyed.

On July 13th I did a local GGS (Gyro gunsight) test for one hour in the Tempest V, No. EN529. I little thought that this would be my last flight as the Flight Commander and Acting O/C Flying at AFDS. One of the new boys took over, recently returned from a hectic tour in Europe, Flight Lieutenant Fifield.

The last of the piston-engined fighters, the Mk 22 Spitfire and the Tempest V version, known as the Fury or Sea Fury, were undergoing trials. A little later the last of the true Spitfires, the Mk 24, appeared. Later still the almost completely redesigned aircraft appeared. It would have been the Mk 25 but, with its wide track undercarriage and straight-edged laminar flow wing, like the Mustang and the German FW190, it was so different that the RAF version was renamed the Spiteful. Not many were built and most of them went to the Fleet Air Arm, where they were known as the Seafang.

Later versions of the Meteor were also undergoing trials. In fact, in 1946 a new High Speed Flight was formed, commanded by Group Captain R.A. (Batch) Atcherley, one of the pre-war team. My old friend Bill Waterton was a member of the team. That year a successful attempt by Edward Donaldson in a Meteor F Mk 4 briefly held the world speed record, following the success of the same plane in 1945, piloted by H.J. Wilson. On the coastal path between Rustington and Littlehampton in Sussex there is a bronze plaque confirming the event. Also appearing at AFDS was the single-engined jet, the DeHavilland Vampire. Sadly, I did not get to fly these new machines, something I now regret.

| Summary for:– June, July 1945 | 1. Spitfire IX | −50 |

| Unit:– AFDS Tangmere | 2. Meteor III | −25 |

| Date:– July 31st 1945 | 3. Auster | 1–10 |

| Signature:– H.L. Thorne | 4. Tempest V | 1–00 |

| | ||

| Signed H.L. Thorne , Acting pp S/Ldr O/C Flying AFDS |

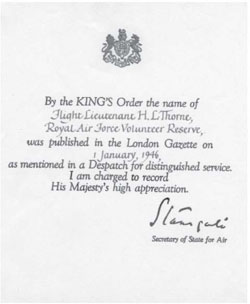

F/Lt Herbert Leonard Thorne, AE, MiD, 1945.

Towards the end of July 1945 I received a telephone call from a friend, a former AFDU Flight Commander, Wing Commander Ron Brown, to say that there was a vacancy at Staff level in the Air Ministry. The chosen candidate was to be attached to the MOS (Ministry of Supply) as a liaison officer between the service and the aircraft manufacturing companies. Although I thought my educational background would mar my chances, Ron suggested that I attend an interview with his Group Captain. So, in August on VJ Day, I presented myself to Thames House South in London. To my surprise I was offered the posting, on condition that I remained in the Service for at least three years. I remember walking back to the car park, watching the crowds on the Embankment setting off fireworks, dancing and singing to celebrate the victory over Japan.

As there was no Service accommodation in London it meant a move from Bracklesham and finding some furnished quarters in the London area. We found a furnished house on the south side of Slough, very near to the Eton College playing fields and only two miles from Windsor. The location was very handy for us to visit Doris, my eldest sister and her policeman husband Percy Climer, who was stationed in Slough. I had lived with them from 1934 to 1939, finished my grammar school education at Slough Secondary School and started my working life at the High Duty Alloys factory in the town, so I had many friends there. As Estelle had worked as a secretary in the CID police office she, too, had many friends in the vicinity. Shortly after we took up residence in Slough my old school friend Freddy Deeks and Dorothy were married on 18th May 1946, Gill’s third birthday. We remained lifelong friends.