A World Lit Only by Fire (48 page)

Read A World Lit Only by Fire Online

Authors: William Manchester

T

HE LITTLE

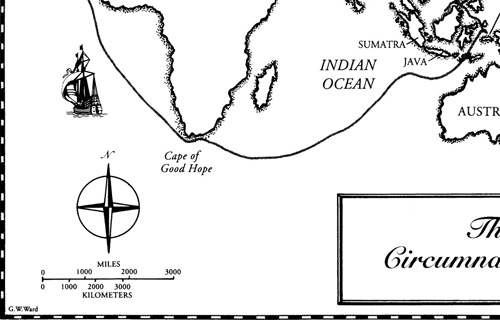

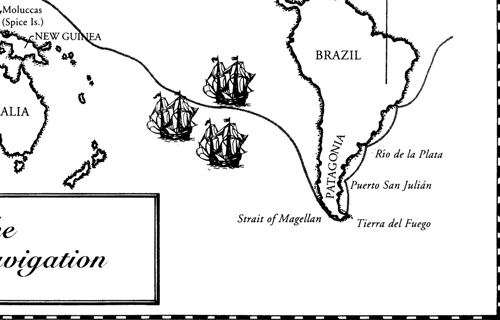

armada’s 12,600-mile crossing of the Pacific, the greatest physical unit on earth, is one of history’s imperishable tales

of the sea, and like so many of the others it is a story of extraordinary human suffering, of agony so excruciating that only

those who have been pushed to the extremes of human endurance can even comprehend it. Lacking maps, adequate navigational

instruments, or the remotest idea of where they were, they sailed onward for over three months, from November to March, moving

northwestward under frayed rigging, rotting sails, and a pitiless sun.

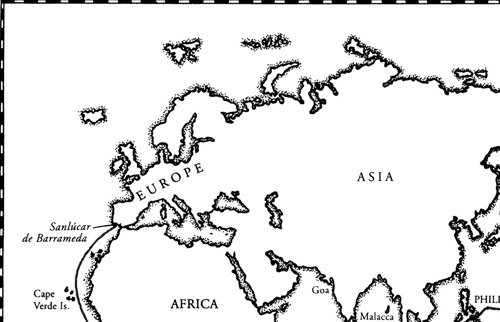

Even for the age of discovery, Magellan’s situation was unique. Previous explorers had known that if all else failed, they

could always return to Europe. That option was closed to him. Ignorant of South America—having started from the mouth of

a strait known only to him—he had no base to fall back upon. Once he had left the eastern horizon behind, he had to sail

on—and on, and on.

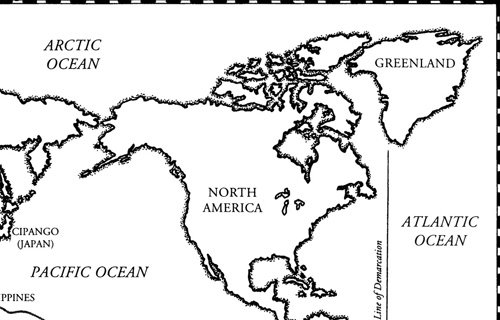

He had no way of knowing the true width of the Pacific. All the information available to him vastly underestimated its extent.

In Europe it was assumed that everything depended upon the location of Ptolemy’s Terra Australis Incognita, a necessary balance

for a spherical world, without which the entire planet would topple over. But some assumptions had been made, and Magellan

was acting upon them. In fact they were all wrong. Had he been told the actual distance that lay ahead of his small boats,

he would have been incredulous; no one in Europe had ever dreamed that so broad a sea even existed. It was as though all his

sources of information—the cartographers, astronomers, and cosmographers of the time—had conspired to betray him. Schöner’s

globe, then thought reliable, put Japan only a few hundred leagues west of Mexico. Indeed, everything Magellan had read or

heard had encouraged him to believe that after a short cruise he would raise Dai Nippon. Instead he was lost on the earth’s

greatest ocean, a trackless seascape so enormous that if all the earth’s landmasses were dumped into it, thousands of miles

of water would still remain.

The expedition had left Sanlúcar with 420 casks of wine. All were drained. One by one the other staples vanished—cheese,

dried fish, salt pork, beans, peas, anchovies, cereals, onions, raisins, and lentils—until they were left with kegs of brackish,

foul-smelling water and biscuits which, having first crumbled into a gray powder, were now slimy with rat droppings and alive

with maggots. These, mixed with sawdust, formed a vile muck men could get down only by holding their noses. Rats, which could

be roasted, were so prized that they sold for half a ducat each. The capitán-general had warned them that they might have

to eat leather, and it came to that. Desperate to appease their stomach pangs, “the famine-stricken fellows,” wrote Antonio

Pigafetta, who was one of them, “were forced to gnaw the hides with which the mainyard was covered to prevent chafing.” Because

these leather strips had been hardened by “the sun and rain and wind,” he explained, “we were obliged to soften them by putting

them overboard four or five days, after which we cooked them on embers and ate them thus.”

The serenity of the Pacific maddened the crews. Yet, as Don Antonio realized, it also saved them: “But for the grace of God

and the Blessed Virgin in sending us such magnificent weather, we should all have perished in this gigantic ocean.” Some died

anyhow; nineteen succumbed to starvation and were heaved overboard. Those left were emaciated, hollow-cheeked wraiths, their

flesh covered with ulcers and bellies distended by edema. Scurvy swelled their gums, teeth fell out, sores formed inside their

mouths; swallowing became almost impossible, and then, for the doomed, completely impossible. Too weak to rise, some men sprawled

on decks, cowering in patches of shade; those able to stand hobbled about on sticks, babbling to themselves, senile men in

their early twenties.

No other vessels crossed their path; indeed, in the six months that passed after they left San Julián they did not encounter

another soul. False hopes were raised twice, about halfway through their ordeal, when islands were sighted which proved to

be uninhabited and with no bottom for anchoring. Finally, on March 6, 1521, when the life expectancy of the hardiest of them

could have been measured in days, they made a genuine landfall. It was Guam in the Marianas, then a nameless isle which, they

found, was inhabited by hostile Micronesians—natives who were alienated, perhaps, by the stench emanating from the very

bowels of the three wretched ships. Nevertheless Guam provided them with a reprieve. After a warrior party had paddled out

to the fleet and stolen a skiff, Magellan sent forty armed men ashore to recover it. They returned with the skiff, and, far

more important, fresh water, fish, fruit, poultry, and meat.

Pressing on after three days of convalescence,

Trinidad, Conceptión

, and

Victoria

sighted the large Philippine island of Samar on March 16, and then, south of it, tiny Suluan and its neighbor, Homonhon,

in the entrance to what is now Leyte Gulf. According to Pigafetta, the capitán-general believed that he had found the Moluccas,

but that is highly improbable; Magellan was too skillful a navigator, and knew Oceania too well, to have confused north and

south latitude. The Spice Islands were over a thousand miles away. The likeliest explanation for Don Antonio’s confusion is

that the admiral, realizing there was no hope of wrenching the Moluccas away from Portugal, had decided to make amends by

staking another claim in the name of the Spanish king. And that is precisely what he did, declaring the archipelago, together

with all men and beasts therein, to be the property of His Christian Majesty, the sovereign of Castile and Aragon.

*

He had chosen to go ashore on Homonhon because it appeared to be uninhabited; his men were too sick to cope with another unfriendly

reception. But some natives, beaming with hospitality, crossed over from Suluan bringing quantities of oranges, palm wine,

fowls, vegetables, and an abundance of two nutritious delicacies new to the Europeans: bananas and coconuts. When the admiral

responded with gifts of bright kerchiefs, bells and bracelets of brass, gaudy red caps, and colored glass beads, they were

delighted.

In their pleasure the capitán-general found a kind of retroactive exoneration. The port officials in Sanlúcar had laughed

at his cargo manifests listing such gewgaws. Indeed, the privy council in Valladolid had at first balked when it found itself

being billed for, among other trifles, a thousand mirrors, fifty dozen pairs of scissors, and twenty thousand noisemakers.

He had explained that he anticipated possible difficulties in establishing rapport with strange natives, and his service in

the Orient had convinced him that trinkets would smooth the way. After he had once more paraded his knowledge of islands —

even exhibiting his Malayan slave Enrique—the privy council had deferred to his judgment, but the ridicule of the officious

panjandrums on the docks had rankled him.

Enrique was still with him, and now, three years after he had been a privileged spectator at his master’s royal audience,

this retainer unexpectedly presented him with a gift beyond price. On March 25, during their second week in the Philippines,

the expedition moved on to the neighboring island of Limasawa. They were in the Visayan Islands, a part of the enormous Philippine

archipelago which is linked, culturally and linguistically, with Sumatra and Malaya. Shortly after they had landed on the

new island Magellan heard a great cheering and, moving toward the noise, found his servant surrounded by merry natives. It

took a while to sort things out. Born in the Visayans, Enrique had been sold into slavery in Sumatra and sent to Malacca, where Magellan had acquired him. Since leaving the Malayan Peninsula in 1512,

he had accompanied his owner to India, Africa, Portugal, Spain, and, for the past eighteen months, on this voyage. An apt

linguist, he was fluent in both Portuguese and Spanish, but here on Limasawa, for the first time since his childhood, he had

overheard people speaking his native language. He had joined in, and they had welcomed him as one of their own.

The significance of this incident was enormous. Enrique was merely happy, chattering away in Malayan, but Magellan was ecstatic.

Both were back on familiar ground, which meant that by sailing westward they had returned to the lands where they had first

met. Obviously Enrique was the first circumnavigator of the world. By completing the circuit of the globe, the expedition

had provided the first empirical proof that it was a sphere.

I

N

C

HRISTENDOM

it was Semana Santa, Holy Week. A full year had passed since the San Julián mutiny. The paso had been found and threaded,

the great ocean crossed, and the earth circumnavigated. Magellan and his men were rejoicing, riding high on a cloud of euphoria,

which was both understandable and ominous—ominous because they were celebrating in one way, he in another, and the two would

become irreconcilable. They entered a collision course after April 7, when Magellan spent three days sailing his flota to

the much larger island of Cebu, between Leyte and Negros. There the interplay between the commander and his crews took on

overtones of dramatic conflict, which was to end tragically.