A World on Fire: Britain's Crucial Role in the American Civil War (92 page)

Read A World on Fire: Britain's Crucial Role in the American Civil War Online

Authors: Amanda Foreman

Tags: #Europe, #International Relations, #Modern, #General, #United States, #Great Britain, #Public Opinion, #Political Science, #Civil War Period (1850-1877), #19th Century, #History

Four days later, on August 7, Lyons was distressed to see his suspicions confirmed. “An impending quarrel with England is allowed to be put forward as a lure to Volunteers for the Army,” he informed Russell. Seward’s latest dispatch to Charles Francis Adams predicted war if the British government failed to halt the Confederates’ shipbuilding program. Seward knew that Adams would never show such a threatening letter to Lord Russell; and Lyons knew it too, telling Russell, “It will not, I suppose, be communicated to you, but will first see the light when Congress assembles in December.”

47

Lyons was about to leave for a short visit to Canada when Seward waylaid him with a proposition to spend the last two weeks of August exploring northern New York State: all the foreign ministers had been invited. Lyons could think of few things less appealing than being dragged through the wilds with the very people he wished to escape. But, he confessed in a private letter to Lord Russell, Seward “has made such a point of my going with him, that it has been impossible to get off without telling him plainly that I’d not choose to travel with him. This of course I could not do; and he deserves some consideration from us.”

48

Lyons would not have felt so guilty if he had known the reasons behind Seward’s invitation. The secretary of state had been entertaining for some time the idea of a summer jaunt with the diplomatic corps, which would allow him to demonstrate his charming side and the North’s booming economy all at the same time, but he only went forward with his plan when he needed a cover for visiting Judge Samuel Nelson of the Supreme Court. Opponents of the draft were mounting legal challenges and the administration wanted to be sure that the Court would make the right decision. Judge Nelson happened to live in Cooperstown, in upstate New York.

On August 15 the large party of diplomats and officials boarded a special train for New York; Lyons had brought along two attachés so he would not have to do all the talking. Contrary to his fears, Seward behaved with impeccable manners throughout the journey; ice cream was provided when it was hot, and carriages for those who preferred to explore sitting down. This rarely seen side of Seward touched Lyons. The secretary of state was incurably vain, he told Russell, but the more one knew of him, the more there was “to esteem and even to like.” The trouble lay in Seward’s tendency to overplay his hand, which required Lyons to exercise his “patience and good temper to be always cordial with him.”

49

The two-week excursion ended with a visit to Niagara Falls on August 25. Seward had a long conversation with Lyons before the minister departed for Canada. He began by referring to the problem of British antipathy toward the North. Lyons assured him that pro-Southern sentiments in Britain would dissipate as soon as the war ended, since there would be “nothing to keep it alive. I told him that the important point was public opinion in the United States.” But Seward insisted that something had to be done to change British opinion: “The President could not travel, and the United States had no Princes.” Lyons listened, wondering where this was leading. Then it dawned on him that Seward was floating the idea of paying a goodwill visit to England. The prospect seemed baffling, and Lyons suspected Seward was thinking more of his domestic audience, perhaps for a future presidential run. Guessing how the cabinet would react to such a tour, Lyons gently discouraged the plan. When he heard of it, Palmerston was indeed horrified: “I hope Seward will not come here,” he wrote to Lord Russell. The visit would not change British policy—except for the worse if Seward said something silly. “He is … vulgar and ungentlemanlike and the more he is seen here the less he will be liked.” He would drink brandy with “some editors of second rate newspapers,” and be fêted by the manufacturing towns, but “I doubt whether Seward would be very well received in Society.”

50

Seward soon dropped the idea—to a silent chorus of relief in England.

After the tour’s conclusion, Lyons traveled to Canada in the hope of finally obtaining some rest from his labors. But there he found that the conflict was being enacted in miniature north of the border. Crimpers and recruiters were doing a brisk business along the border towns, turning Canadian public opinion dangerously pro-Southern. The authorities suspected that the Confederates were planning to use Canada as a base for operations, although so far there was little evidence to support these fears.

—

The idea of launching raids from Canada had indeed been suggested to Jefferson Davis, but he remained undecided, worrying that the international community would regard such a move as a last, desperate measure. For the moment, Davis had decided to pursue an alternative course. The North was constantly sending emissaries to meet with influential members of British society, and he was sure that the South had suffered as a result. To redress the balance, Davis had asked Rose Greenhow—whom he remembered as one of the most powerful hostesses in Washington before the war—to travel to England and, as important, to France, with the express purpose of explaining the case of Southern independence. Slidell would help her gain an audience with the emperor, but the rest would be up to her own efforts.

Rose had been living quietly since her arrival in Richmond in June the previous year. Between looking after her ten-year-old daughter, also named Rose, and writing a memoir of her imprisonment in Washington, she had managed to make a semblance of a life for herself. But she had not been happy. The Southern ladies had not welcomed her into their circle; Mary Chesnut waspishly described Rose as “spoiled by education—or the want of it.”

51

President Davis’s request was a welcome rescue not only from her grinding day-to-day existence, but also from the petty disapproval of Richmond society.

There were no other travelers at the Mills House Hotel when Rose arrived in Charleston during the second half of July; the other guests were all black marketeers of some description. Within hours of unpacking, she received a visit from General Beauregard. Knowing that she had a direct link to President Davis, he gave her a frank report of the situation and explained why he needed more artillery. The Federal bombardment was about to resume, and this time the Confederates expected it to continue until the city surrendered.

Rose’s next guest was Frank Vizetelly. “He gives me all that he gathers, altho’ under the seal of confidence as I told him I should tell you,” she informed President Davis. Vizetelly believed that the shortage of drinking wells around Jackson would soon exact a crushing toll on Grant’s army, having witnessed “eight men within a space of thirty feet fall down from want of water.” This fact alone, he told her, guaranteed that General Johnston would not be driven out of the city. In reality, even as Vizetelly spoke, the Confederates were retreating from Jackson, and in a few hours the city would be in flames. Vizetelly’s passionate advocacy of the Southern cause had temporarily robbed him of his critical faculties. Every judgment, every prediction he made to Rose would turn out to be wrong.

Rose soon came to the conclusion that Charleston Harbor was useless as a means of escape, and she boarded a train with little Rose for Wilmington. Her rooms at the Mills House Hotel did not remain empty for long. On August 7, Fitzgerald Ross and Captain Scheibert checked into the hotel, having left Francis Lawley behind in Richmond. The journalist had pushed himself to the brink of collapse at Gettysburg and was too weak to travel. The pressure of maintaining an optimistic tone in his

Times

reports had also been taking its toll on him.

Fitzgerald Ross recognized Vizetelly from Lawley’s description when the journalist showed up at the Mills House Hotel for dinner. According to Scheibert, “this hotel had the best service of any tavern” in the South. It charged the highest prices, too: $100 per person for a three-course meal.

52

General Beauregard welcomed Vizetelly’s new friends when they called at his headquarters, and introduced them to the English officer on his staff. Henry Feilden was growing used to his role as Beauregard’s mouthpiece and cheerfully gave a tour of the preparations against the next phase of the Federal siege. The consuls observed with alarm that more gunships were sailing into the harbor. The city itself was obviously the next objective. The British consul, Henry Pinckney Walker, sent a message to the legation in Washington that somehow slipped through, beseeching Lord Lyons to send a British warship to rescue the “several thousand” British women and children who were in the direct line of fire.

23.4

53

At 10:45

P.M.

on August 21, a note from Union general Quincy Adams Gillmore was delivered to Beauregard’s headquarters announcing the imminent bombardment of the city. He had neglected to sign it, so no one took the threat seriously. Three hours later, the shelling began. “At first I thought a meteor had fallen; but another awful rush and whirr right over the hotel and another explosion beyond, settled any doubts I might have had,” wrote Vizetelly. He threw on his clothes and ran down the stairs, fighting his way past hysterical businessmen. “One perspiring individual of portly dimensions was trotting to and fro with one boot on and the other in his hand, and this was nearly all the dress he could boast of.… Another, in a semi-state of nudity with a portion of his garments on his arm, barked the shins of everyone in his way in his efforts to drag an enormous trunk to the staircase.”

54

Out in the street, women were running in all directions, their heads ducked, some carrying children in their arms. Many people were stampeding toward the station in the wild hope that a train would be waiting to convey them away. Vizetelly found Ross and Scheibert coolly standing around in the Mills House bar. He persuaded them to come with him down to the promenade, where they would have a better view of the bombardment. To their surprise, a large crowd had already gathered there. For an hour they stood out under the open canopy of stars, with Vizetelly and Ross taking bets as to whether the shells would fall short and land on their heads.

55

The next morning, General Beauregard sent a furious note to Gillmore demanding a halt to the firing until all the civilians could be evacuated. The British consul called on General Gillmore under a flag of truce with a similar request. The Federal commander granted a cease-fire of twenty-four hours before resuming the bombardment. After three weeks of continuous shelling, the excitement wore thin, and the three friends began to discuss their departure from Charleston. On September 14, Ross and Vizetelly bade farewell to Scheibert, who was returning to Prussia. “I fear our troubles have only begun,” Thomas Prioleau wrote to his cousin Charles Prioleau, the head of Fraser, Trenholm in Liverpool. “The fire brought against us is immense and incessant, yet we do not despair.”

23.5

56

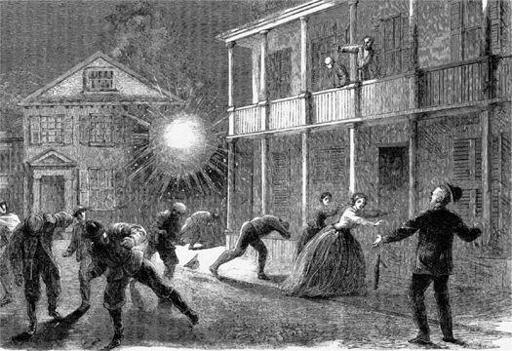

Ill.45

Downtown Charleston under fire from Union forces, by Frank Vizetelly.

23.1

While Mayo was exploring Vicksburg, he was the subject of cheerful conversation at home. On July 11, 1863, the

Medical Times and Gazette

reported on the dinner held by the Southampton Medical Society: “Mr. Dayman spoke at length: ‘A son of one of their old associates, Mr. Mayo, of Winchester (hear, hear), was at that moment with the army in America.’ (A deeply-toned Voice: Yes, but on the wrong side—laughter.) “There were no wrongs on the side of Surgery.” (Hear.) (A Voice: I should prefer his being in the south. Another Voice: The north is more bracing, and laughter.) ‘Their young friend, Dr. Chas. Mayo, was with the army in North America.’—(A Voice: The right man in the right place, and laughter.) ‘He was gone out as a volunteer Surgeon, taking with him no prejudiced views of the supremacy of Military Surgery, but content to carry into the field the principles which had made his father.… Might their young friend do justice, not only to Hampshire, but also to England.’ (Applause.)”

23.2

Adams had also canceled the legation’s Fourth of July celebration. The previous year’s dinner had been a desultory affair. He expected this year’s to be no better, and he feared a visit from the popular orator Henry Ward Beecher, brother of the author Harriet Beecher Stowe, who was visiting England on a lecture tour. Beecher was arousing the British public, but for all the wrong reasons, telling a gathering of temperance campaigners, for example, that the North was losing because its army officers could not stay sober.