Read A Zombie's History of the United States Online

Authors: Josh Miller

A Zombie's History of the United States (15 page)

SIX

Manifestering Destiny WESTWARD EXPANSION AND THE AMERICAN OLD WEST

Washington is not a place to live in.

The rents are high, the food is bad, the Carries

are everywhere, and the morals are deplorable.

Go West, young man, go West and

grow up with the country.

—Horace Greeley, founder of the New York Tribune, July 13, 1865

The period between the end of the War of 1812 and the beginning of the American Civil War has been called the Age of Manifest Destiny, when America systematically went about consuming land and redefining the contiguous borders of the country to those dimensions we still boast today. The Texas Revolution had freed up Texas and parts of present-day New Mexico, Oklahoma, Kansas, Colorado, and Wyoming; the Oregon Treaty of 1846 acquired Oregon, Washington, Idaho, Montana, and further parts of Wyoming; and the Mexican-American War (1846-48) gave us California, Nevada, Arizona, Utah, and the remaining portions of New Mexico, Colorado, and Wyoming.

“Manifest Destiny” was a term coined by New York journalist John L. O’Sullivan in his editorials supporting the annexation of Texas in 1845, which, though broken from Mexico at the time, was not yet officially a part of the United States. O’Sullivan and many others believed that America was destined to expand across the continent by divine right, to tame the wild and spread American values. Whether it was predestined to or not, expand America did. At the end of the Civil War, a great number of Americans found their former lives shattered. For them, spreading American democracy mattered little. The West offered fresh starts and new opportunities, and that was reason enough to pack up and try their luck.

Over the decades, the United States had ruthlessly driven the Indians westward through war and broken promises. The First Cleanse had done the same with a massive section of the zombie population. With so many Indian tribes relocated to areas with which they were unfamiliar, many found themselves out of sync with their previous zombie defense systems. It was disastrous. Entire tribes and nations who had thrived in North America for centuries were suddenly wiped out through devourment or zombination. Many areas became wastelands—where the zombies ruled.

Now, in a moment of historical comeuppance, the zombies lay in wait for these hopeful new westward travelers.

Eureka!

Conflict with the dead was almost instantaneous.

—Chester Marks, miner, 1854

James W. Marshall was a foreman overseeing the construction of a lumber mill along the American River, near Coloma, California when, on January 24, 1848, he found flecks of a shiny metal in the mill’s water wheel. Those tiny flecks were to cause one of the most famous population booms in American history—the California Gold Rush.

At the time of the discovery, California was still part of the Mexican territory of Alta California, but when the Mexican-American War ended shortly thereafter, the territory was ceded to the United States. Word spread fast around California, and gold-hungry prospectors eagerly came to see if the stories about the Mother Lode were true. Not until August did the rumors start reaching the East Coast, and it was not until December that President James Polk con firmed to the United States that the rumors were true. Soon wave after wave of gold-fever-infected immigrants from around the world descended on the Coloma area.

THE DONNER PARTY

The tragedy that befell the infamous Donner Party, whose wagon train became snowbound in the Sierra Nevada on their way to California during the winter of 1846-47, forcing the party members into cannibalism, is often falsely attributed to zombies. This is a complete fabrication, though. None of the survivors, even those who denied acts of cannibalism, ever mentioned zombies. The zombie story can probably trace its roots to a popular dime novel from the 1860s titled,

The Donner Massacre

, which reimagined the tragedy as a zombie siege.

In 1849, 90,000 people settled in the California gold country, which later earned them the nickname, “the fortyniners.” By 1850, some 300,000 more had made their journey. The original residents of gold country had always had zombies to deal with, but nothing that could not be contained. With such a sudden and massive increase in population, and no formal civic authority or zombie watches in place, the area became a zombie paradise. Whole families or crews would get wiped out by roving hordes, yet there was always another crew ready to jump the claim before the rain had even washed the blood away. Often this new group would meet the same grisly fate, but as long as the claim was still yielding, the cycle would continue.

By most standards the area became something of a lawless hellhole. Prior to Marshall’s discovery, San Francisco had been a small settlement of 1,000 people, but soon it exploded, becoming a major world port. Now San Francisco was teaming with zombie brothels, gambling establishments, and exhibition rings where down-on-their-luck immigrants could wrestle zombies in hopes of winning cash prizes, food, or land grants.

Then in 1859, silver ore was discovered on Mt. David-son, near what is now Virginia City, Nevada. Known as the Comstock Lode, it saw yet another population boom, as mining camps popped up all over the mountain. The deep mines that were constructed to follow the veins of precious ore were dangerous enough because of cave-ins, flooding, and toxic gas; however, if zombies found their way into a mine, it spelled certain doom for the miners inside. Dogs trained to bark at zombies were often placed at junctions along a mineshaft to alert the miners of a breach, but such measures were not always enough.

A particularly terrible accident occurred in 1864 in Mt. Davidson’s Sandro Tunnel. Sandro spanned a labyrinthine three miles underground, at depths of 1,500 feet, and was by all accounts one of the most safely constructed and operated mines anywhere in the country at the time. Sadly, Sandro’s overseers could not control the messy history of the Nevada silver mining industry. During Comstock’s frenzied infancy, a too common practice for dealing with zombie accidents was to force a cave-in in the infested section, sealing the zombies off from the rest of the mine. Detailed records and maps were not always kept for many of these tunnels. Such was the case with the Lewis-Pullman Tunnel, which had sealed off a portion of its mine when zombies attacked in 1861. On July 10, 1864, workers expanding the Sandro Tunnel hit the quarantined section of the Lewis-Pullman. As a surviving miner later told the

Silver City Reader

:

We new right off we hit another shaft. My brother Henry and some others went into the hole with lanterns. Then they was a screaming. Saw Henry tried to come back out but he got pulled up off his feet. I grabbed his hands, a pulling him, but he just got pulled back into the black. Knew it right off that we hit a dead pocket. Then them things were pouring in.

The miners panicked. Some ran while other foolishly attacked the zombies with torches and lanterns. As some of the zombies caught on fire, the flames began to spread through the tunnel. Mine explosions were a constant danger, but up to this point the miners were still lucky, as an explosion would have occurred instantly if it were possible. The small fires would likely have burnt themselves out and the remaining zombies eventually de-animated with little problem, but tragically, one of the burning zombies chased a miner into a mule stable (mules were used to pull loaded cars through the tunnels), and the stable’s hay supply was set ablaze. Soon the support beams in the tunnel caught on fire. The heat and smoke became overpowering, far eclipsing the danger posed by the zombies. In the tunnel, 259 men lost their lives, and the Sandro was closed, too damaged to ever reopen.

Though zombies had only been responsible for 4 of those 259 deaths, the Sandro Tunnel Fire is still categorized as the worst zombie-related disaster in mining history.

Connecting the Coasts

The dead have killed four men. When the men go to work, even if they are in full sight of the camp, they go well armed. I counted ten guns, most of them breech-loading. Something like the times of 1776.

—Samuel Reed, Union Pacific surveyor, diary entry, May 22, 1867

The First Transcontinental Railroad, originally known as the Pacific Railroad, was a joint effort between Union Pacific Railroad and Central Pacific Railroad of California, which connected the terminus at Omaha, Nebraska, with that at Alameda, California, on the San Francisco Bay, creating what Lewis and Clark had been searching for a half-century earlier—a shipping route connecting the Pacific and Atlantic oceans. This railroad was the single greatest feat of American engineering until the Panama Canal more literally connected the two oceans.

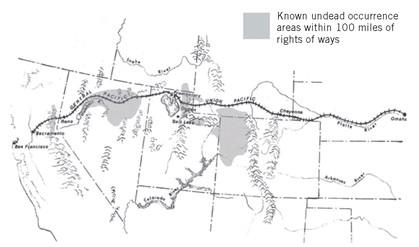

The Transcontinental Railroad, 1869 (courtesy of the National Parks Service).

The railroad’s construction spanned from 1863 to 1869, but work began on the project much earlier. In May 1853, John Williams Gunnison, an officer in the military’s Corps of Topographical Engineers, was assigned to survey a route through the Utah Territory for the potential railroad. On the morning of October 26, 1853, after Gunnison had split his group into two detachments, Gunnison and the eleven men in his party were attacked by a horde of zombies near Lake Sevier, Utah. Five of his men managed to escape and alert the other detachment, but by the time they returned, six of the remaining eight men had been devoured, the other two, including Gunnison, had been zombinated.

The incident was sadly commonplace and would surely have become a mere footnote in the history of westward expansion were it not for the scandal that erupted following the massacre—for Gunnison and his men had encountered a group of Mormons immediately preceding the attack. Most accounts of the massacre maintain that the Mormons dutifully warned Gunnison that there was a large zombie horde in the area. Gunnison even records that when they first encountered the Mormons, they found them “all gathered into a village for mutual protection against the Utah undead.”

LIFE OF DEATH

The Mormons were not the only ones to relocate to the West seeking freedom from religious and cultural persecution. In 1858, a group of hybrids, led by James Reynolds, relocated in upper New Mexico to form a small, all-hybrid community. Reynolds had been a Methodist pastor when he became a hybrid. Supposedly he then had an epiphany, receiving a message from Jesus Christ himself, who informed the pastor that he, Jesus Christ, was in fact a hybrid. Jesus’s followers had misinterpreted his return from the grave. God had made him the first hybrid, and it was from his blood that all hybrids now flow. The hybrids’ recent arrival on earth was Jesus’s second coming: this was the Rapture.

Reynolds started the Life of Death church in Tennessee and hybrids from across the country flocked to the church, taking on the somewhat comical name of Deathodists. Not all hybrids bought into Reynolds claims, especially John Blackburn, who said the Life of Death church was “too farcical to even be considered blasphemy.” But the church’s number grew, and even began attracting humans, who would then go through a baptismal ceremony in front of the congregations, bitten by Reynolds or another high priest and infected with the hybrid strain. When the Deathodists began actively recruiting new human members, the rest of the human population inevitably reacted angrily, and often violently. So Reynolds and his congregation headed west where they might “live” in peace.