A Zombie's History of the United States (4 page)

Read A Zombie's History of the United States Online

Authors: Josh Miller

Like witch trials, most evidence presented against someone accused of being a living zombie (as it were) was simply hearsay and eyewitness testimonies. Those men believed to be undead often partook in extramarital affairs or other sinful practices. There were also superstitious telltales, such as sleepwalking or allergies to cats and dogs (which were generally believed to be able to sense evil). If multiple men had been rounded up, with one or more believed to be zombies, a “dead cake,” it was believed, could be used to discover the guilty member or members. The cake would be made of rye meal and urine from the accused men. The cake would then be fed to a dog. Once consumed, the dog would supposedly be able to point out which of the men was a zombie.

In the more fanatical cases, the most conclusive way to determine a man’s innocence of being undead was simply to kill him and see if he rose from the dead. Those found guilty by “fair” trial in court were burnt at the stake to make sure they did not rise from the grave, which also conveniently made rising from the grave impossible, of course. Eventually there was a public backlash to “undead hunts.” Many of these so-called trials were hasty and built on flimsy evidence, and became increasingly polarizing. By the early 1700s there was a major shift away from the kind of beliefs propagated by people like Kramer. That isn’t to say Christians stopped believing zombies were the work of the devil, but they did not necessarily believe that a man could secretly be a zombie; at least not enough people believed this for it to pose a problem to colonial sleepwalkers. Many cities and courts even (posthumously) overturned rulings against convicted zombies, in some cases, even financially compensating their families.

Settling In and the Undead Act

To the matter of whethnot the Abominations have souls; No. They mock the very gifts of God in their rude mummery of Life.

—Cotton Mather, Puritan minister, 1698

Even if living zombies were not actually trying to seduce lonely farmers’ wives, zombies were posing a very real problem for the early English settlers. Already strained by an unprepared workforce, the colony was losing people, and not just to zombie attacks. Many settlers chose to defect to the safety of the Indian tribes. The Indians knew how to work the land for food and, more importantly, they knew how to deal with the zombie population. This bred a sort of resentment in many of the colonists, who believed themselves to be more civilized than the Indians.

In 1676, Nathaniel Bacon lead an uprising of frontiers-men, slaves, and servants against the governor of the Virginia Colony, in what became known as Bacon’s Rebellion (the first rebellion in American history). Settlers who had been overlooked when huge land grants around Jamestown were given away had gone west to find land, and there they encountered zombies. The uprising began with conflict over the colony’s refusal to send support to help fend off these zombie hordes. The rebellion was ultimately suppressed but it showed colonial leaders that zombies needed to become their concern too. It also encouraged people to move into cities, thinking they served as better protection against zombies.

By the turn of the 18th century, Scotch-Irish and German immigrants were joining the English settlers. Black slaves were pouring in by the boatload. The big cities—Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Charlestown—were doubling and tripling in size. Of course, the increase of food supply—the food here being

us

—saw a sharp increase in the zombie population too. Though exact numbers are difficult to gauge, it is estimated that zombies made up 1 percent of the population in 1640. By 1740, the number had jumped to a staggering 9 percent. Of the 1.04 million people living in the English colonies, 93,600 of those individuals weren’t quite

living

.

Newspapers wrote about the swelling “Number of wandering Dead.” Demand arose for institutions to contain the “many Grotesque individuals daily suffered to walk about the Streets seeking to bite and otherwise molest.” A New York City Council resolution read:

Whereas the Necessity, Number and Continual Increase of the Misdead within the City is very Great and… frequently Commit diverse misdemeanors and graver acts within the Said City, who living Idly and unemployed, seek to devour and otherwise Dismember the Good citizens. For Remedy Whereof… Resolved that there be forthwith built a good, Strong and Convenient House and Corral.

The resulting two-story structure was called the Dead House. By the mid-1700s all the big cities built dead houses, though soon they became home not just to zombies, but the elderly, widows, cripples, orphans, the unemployed, and new immigrants—many of whom were regarded as no better than the flesh-hungry zomboids. These unfortunate souls would generally became zombies themselves soon enough in such an environment, further contributing to the problem.

A sharp class division was forming in regard to zombie defense. Put simply, those with money could afford the architectural and manpowered security required to guarantee their family’s safety. Those who didn’t have the money could not and were left to the dangers of attacks. Even at the very start of the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1630, the governor, John Winthrop, had declared the philosophy of the ruling class:

…in all times some must be rich, some poore, some highe and eminent in power and dignite, others meane and in subjection and fodder for the foully Resurrected.

In other words: the lower classes were zombie chow.

This class separation saw the rise of a powerful middle class. New Yorker Cadwallader Caulden, in his

Address to the Freeholders

in 1747, attacked the wealthy as tax dodgers unconcerned with the welfare of others and the growing zombie problem. Nathaniel Prestwood, a prominent Virginian tanner, even went so far as to travel to England where he pled directly to King George II for more assistance against the zombies. Prestwood’s efforts, among others, finally led Parliament to pass the Undead Act of 1749.

The Undead Act had the opposite effect of appeasing the colonies. Not only did it prove to be very unpopular, it was met with outright protest in many areas. The crux of the act was the Church of England’s proclamation that zombies were an affront to God. This required all the dead houses to be closed and all the zombies within, and roaming the streets, be destroyed. The problem was that Parliament provided no funds or extra military support to assist their command, forcing the colonists into unwanted confrontations with the zombies.

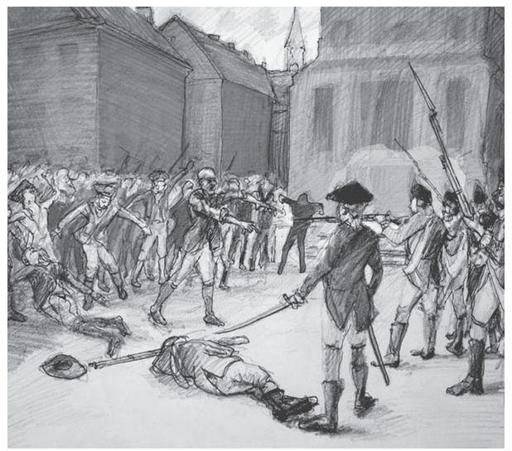

Some cities, such as Philadelphia, chose to burn down their dead houses—with the undead inside—but in a time before hydrants and organized fire departments, it was a risky plan (with notable failures). Most cities elected simply to clear the dead houses out, which required huge mobs to subdue the zombies. Boston suffered Hell Friday on October 3, 1749, when citizens refused in protest to aid in a zombie roundup. The carnage that followed saw the implementation of the “see-and-shoot” law in Boston. The see-and-shoot law legally required citizens to attack and kill any zombie they saw. Those witnessed not aiding others in a zombie attack could be punished with a fine or jail time. Archaic but effective, see-and-shoot laws quickly spread to several other cities. New York was still practicing see-and-shoot until establishing official police services in 1845.

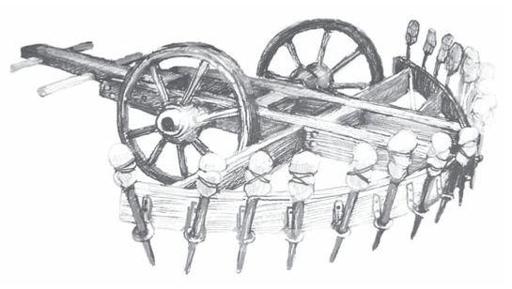

The anti-zombie Fire Hook.

In 1751 there was The First Cleanse, or Harron’s War (named after Bishop John Harron, who championed the event), a series of organized zombie purges throughout the colonies from May through August. Posses formed for the purposes of de-animating zombies were nothing new. What made Bishop Harron’s plan unique was the radical idea of relocating the zombies. De-animating zombies with bullets and decapitations was dangerous and time-consuming, but Harron had a new instrument to add to the cause: the Fire Hook. Developed by Charles Luvel DeMett at the bishop’s behest, the Fire Hook was a wheeled cart with a crescent shaped bar to which as many as twenty torches could be affixed. Fire was then the only thing zombies were known to be afraid of. With several men pushing the Fire Hook, zombies could be driven away or corralled with reasonable effectiveness.

Hailed as a small success, The First Cleanse was of course only a temporary fix, as all it accomplished was driving the zombies into Indian territory. Over time this created incredibly dense hordes of zombies in the West, but that was a problem for future generations.

Viewed as a hollow pronouncement in its time, the Undead Act was the first step toward the complete removal of zombies from American life, to the world we now live in. The act was also one of the many colonial grievances that would soon swell into the War for Independence.

TWO

A Revolting Revolution AMERICA’S FIGHT FOR INDEPENDENCE

These are the times that try men’s souls; the summer soldier and the sunshine patriot will, in this crisis, shrink from the service of his country; but he that stands it

now

, deserves the love and thanks of man and woman. Tyranny, like a rotting deviled walking corpse, is not easily conquered; yet we have this consolation with us, that the harder the conflict, the more glorious the triumph.

—Thomas Paine, The American Crisis, 1776

Starting with Bacon’s Rebellion in Virginia, by 1763 there had already been eighteen uprisings attempting to overthrow local governments in the colonies.

England had just defeated France in the Seven Years’ War (known stateside as the French and Indian War), and expelled French power from the continent. The British had wooed the Indians by declaring Indian lands west of the Appalachians off limits to colonials. Ambitious colonial leaders were of course furious, their chances for expansion now dashed, but the average colonist was far more concerned by a provision in the Royal Proclamation of 1763 that forbade them from driving zombies into Indian territory, which had remained a popular practice since The First Cleanse.

Making matters worse, the British needed to recoup investment from their costly war with France, and the colonies were where they expected the revenue—colonial trade had become increasingly important to the British economy—but by this stage the English were in far greater need of colonial wealth than the colonials were in need of British leadership. The situation was ripe for conflict.

The Creeping Lurch to War

Among the natural rights of the colonists are these:

First a right to life, secondly to liberty, and thirdly

to property; together with the right to defend them

against man and walking dead in the best manner

they can.

—Samuel Adams, The Rights of the Colonists, 1772

In 1768, two thousand British soldiers were still quartered in Boston. The French and Indian War long over, soldiers began taking jobs normally held by colonists at a time when jobs were already scarce. Tensions were at a breaking point when, on March 5, 1770, British soldiers fired into an agitated crowd in front of a customhouse, killing five civilians. The incident became known as the Boston Massacre and was a critical event in turning colonial sentiment against King George III—the rolling snowball that became an avalanche, if you will.