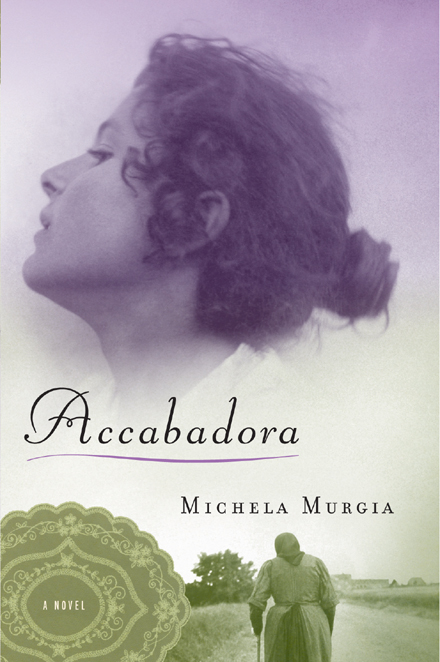

Accabadora

Authors: Michela Murgia

A

ccabadora

ccabadora

A NOVEL

MICHELA MURGIA

COUNTER POINT

BERKELEY

Accabadora

Copyright © Michela Murgia 2012

First published in the Italian language as Accabadora

Copyright © 2009, Giulio Einaudi editore s.p.a., Torino

English translation copyright © 2011 by Silvester Mazzarella

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, businesses, organizations, places and events are either the product of the author's imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or locales is entirely coincidental.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in Publication is available.

ISBN 978-1-61902-133-4

Interior design by Neuwirth & Associates, Inc.

Cover design by Ann Weinstock

COUNTERPOINT

1919 Fifth Street

Berkeley, CA 94710

Distributed by Publishers Group West

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

To my mother.

Both of them.

GLOSSARY

abbardente | highly alcoholic, transparent spirit, sometimes flavoured with wild fennel or arbutus berry |

amaretto | small cake or biscuit made with bitter almonds |

aranzada | softened orange peel with honey, almonds and sugar |

attittadora | woman paid to attend funerals to pray and cry |

babbo | dad, father |

capigliette | filled pastry with almonds and lemon |

culurgiones | small pasta envelopes filled with potatoes, cheese, spices, etc. and served with tomato sauce and grated pecorino cheese |

gueffus | balls of almond paste |

mistral | strong, cold wind coming from the north or northwest |

nuraghe | Bronze Age structure from the Nuragic civilization particular to Sardinia, a truncated conical tower of stone resembling a beehive |

pabassinos | small cakes with either sultanas ( |

pirichittus | filled pastry containing lemon |

saba | a kind of molasses or treacle made with grape must or prickly pear |

tiliccas | filled pastry with |

tzia/tzio | aunt/uncle |

A

ccabadora

Fill'e anima

: soul-child.

THAT IS WHAT THEY CALL CHILDREN WHO ARE CONCEIVED

twice, from the poverty of one woman and the sterility of another. Maria Listru became such a child, late fruit of the soul of Bonaria Urrai.

When the old woman stopped under the lemon tree to speak to the child's mother, Anna Teresa Listru, Maria was six years old, a mistake after three things done right. With her sisters already grown into young ladies, she was playing alone in the dirt, making a mud tart full of live ants with the attentive care of a young housewife. The ants died slowly, waving their reddish legs under the decoration of wild flowers and sand masquerading as sugar. Under the fierce July sun Maria's pudding grew in her hands with the beauty that sometimes characterizes evil things. Looking up from the mud, the little girl saw Tzia Bonaria Urrai smiling beside her, backlit against the bright sun,

her hands resting on her meagre stomach which had just been filled by an offering from Anna Maria Listru. Maria would not understand the significance of that offering until much later.

Still, she went off with Tzia Bonaria that very day, carrying her mud tart in one hand and in the other, her mother's pitiful final gesture to see her on her way, a bag of fresh eggs and parsley.

Maria was smiling. She felt intuitively that there must be a reason to cry, but she could not quite remember what it was. And already, as they left, she was finding it difficult to remember her birth-mother's face, as if she had forgotten it long ago, in that mysterious moment when a young girl first makes up her mind what will be the best ingredients for her own mud tart. But she did remember that hot sky for many years and the feet of Tzia Bonaria in her sandals, one slipping out under the hem of her black skirt as the other was hidden by it, in a silent dance whose rhythm Maria's own legs had difficulty in following

Tzia Bonaria gave her a bed all to herself in a room full of saints, all nasty ones. Thus did Maria learn that paradise is no place for children. Two nights she lay awake, silent, eyes wide open in the darkness, expecting to see tears of blood or sparks fly from haloes. On the third night she gave way to her terror of the sacred heart with the finger pointed at it, made even more alarming by the three heavy rosaries that hung amid the blood spurting from the chest. She could take it no longer, and cried out.

Tzia Bonaria, opening the door a few seconds later, found Maria standing by the wall hugging the shaggy wool pillow she had chosen as her comfort-blanket. She looked next at the

bleeding statue which seemed to be nearer the bed than ever. She carried it away under her arm without a word, and next day the holy-water bowl with a picture of Santa Rita inside it disappeared from the dresser, and so did the mystical plaster lamb, curly like a dog but as ferocious as a lion. It took a while for Maria to begin reciting the

Ave

again, and even then she did it very softly for fear the Madonna might hear and take her seriously in the hour of our death amen.

It was hard to guess Tzia Bonaria's age in those days; she seemed ageless, immutable, frozen in time, as though she had suddenly decided for herself to be much older than her calendar years and was now patiently waiting for time to catch up. Whereas Maria, arriving too late into her mother's womb, had always known she was the last concern in a family already weighed down with cares. But now, in the house of this woman, she began to experience the unfamilar feeling that she mattered. She knew, when she set off for school in the morning, holding tight her textbook, that she had only to turn to see her benefactor standing watching her, leaning against the frame of the door as if holding it up.

Maria was not aware of it, but it was especially at night that the old woman came close to her, on ordinary nights when the little girl had no sin to blame for keeping her awake. Tzia Bonaria would come silently into the room and sit down by the sleeping child's bed, gazing at her in the darkness. Meanwhile, imagining herself first in the thoughts of Bonaria Urrai, Maria would sleep, untroubled as yet by the knowledge that she was unique.

It was perfectly clear to the people of Soreni why Anna Teresa Listru had given her youngest daughter to the old woman. Ignoring the advice of her family, she had married the wrong man, simply to spend the next fifteen years grumbling that he had shown him-self able to do only one thing well. Anna Teresa Listru loved to complain to her neighbours that her husband had been useless even in death since he had not even had the grace to snuff it in the war so as to leave her with a pension. Rejected as unfit for military service because he was so small, Sisinnio Listru had died as stupidly as he had lived, squashed like a pressed grape under the tractor of Boreddu Arresi, for whom he had worked from time to time as a share tenant. As a widow with four daughters, Anna Teresa Listru had dwindled from being poor to being destitute and learning, as she often was heard to say, to make stew with the shadow of the church bell. But now that Tzia Bonaria had asked if she could take Maria as her own daughter, it was almost beyond Anna Teresa's wildest dreams that she could add a couple of potatoes grown on the Urrai property to her soup every day. The fact that her youngest child was the price she paid for this privilege was of little concern to her; after all, she still had three others.

But no-one had the slightest idea why Tzia Bonaria Urrai at her age should have wanted to take another woman's daughter into her home. The silences lengthened like shadows when the old woman and the child passed down the road together, provoking whispered fragments of gossip among those sitting on the village benches. Bainzu, the tobacconist, was inspired to say that even the well-off, when they grew old, needed a second pair of hands to help wipe their bums. But Luciana Lodine, grown-up daughter of

the plumber, could not understand why anyone should need to take on an heir to do what any well-paid servant could do. And Ausonia Frau, who knew more about bums than any nurse, would cap the discussion by declaring that not even vixens liked to die alone, and after this no-one had anything more to add.

Of course it was true that, had not Bonaria Urrai been born into a wealthy family, she would have ended up no different from any other female without a man, let alone have been able to take on a

fill'e anima

. The widow of a husband who had never married her, she would perhaps in a different station of life have been a whore, or have lived out the rest of her life dressed in black behind closed shutters in monastic seclusion either at home or in a convent. She had lost her wedding-dress to the war, even if some did not believe that Raffaele Zincu had really died on the Piave: perhaps he had been crafty enough to find another woman up there and save himself the trouble and expense of the journey home. Perhaps this was why Bonaria Urrai had become old even when still young, and why no night ever seemed blacker to Maria than Bonaria's skirt. But all the local gossips knew the district was full of “widows” whose husbands were still alive, and Bonaria Urrai knew it too, which was why she would walk with her head held high and would never stop to talk to anyone but go straight home stiff as a rhymed verse after going out each morning to collect her new-baked bread.