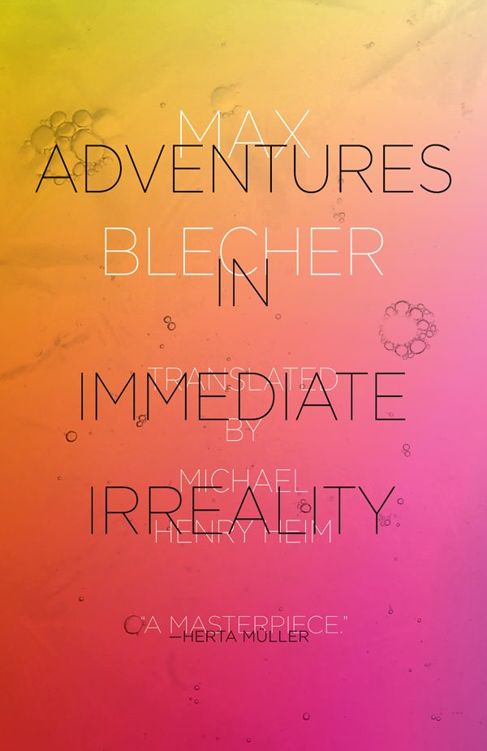

Adventures In Immediate Irreality

Read Adventures In Immediate Irreality Online

Authors: Max Blecher

“I pant, I sink, I tremble, I expire.”

—Percy Bysshe Shelley

Contents

Max Blecher’s Adventures

by Andrei Codrescu

“Every Object Must Occupy the Place It Occupies and

I Must Be the Person I Am”

by Herta Müller

ADVENTURES IN IMMEDIATE IRREALITY

Max Blecher’s Adventures

This is a book that soothes without sentimentality. Blecher

chronicled his dying from both the interior of his body and the outside of

nonexistence. He made that veil permeable: his words are vehicles traveling through

the opaque membrane that surrounds the seemingly solid world. These are the

“adventures” of the inside and the outside exchanging places, while being somehow

exactly the same in the light of Blecher’s extraordinary sensibility. Nobody knows

how to die. Max Blecher, because he was young and a genius, suggests a way that

investigates, rediscovers life, and radiates beauty from suffering.

“Ordinary words lose their validity at certain depths of the soul.”

Max Blecher’s soul was a fearless journalist who reported what his hypersensitive

senses and immense intelligence uncovered about the world we think we know. “The

world as definitively constituted had lain waiting inside me forever and all I did

from day to day was to verify its obsolete contents.” After the discovery that this

is not the real world, he finds it to be the projection of a text that tells a story

which erases the world as it appears to be: “All at once the surfaces of things

surrounding me took to shimmering strangely or turning vaguely opaque like curtains,

which when lit from behind go from opaque to transparent and give a room a sudden

depth. But there was nothing to light these objects from behind, and they remained

sealed by their density, which only rarely dissipated enough to let their true

meaning shine through.”

This is not Surrealism, as critics sometime saw it, but hyper-realism. Blecher

corresponded with André Breton, and was chronologically situated in a string of

Jewish-Romanian geniuses: Tristan Tzara (b. 1886), Benjamin Fondane (b. 1898),

Victor Brauner (b. 1903), and Gherasim Luca (b. 1913). Each of those writers

launched a precocious revolution related to Surrealism, with an urgency prompted by

an imminent and cataclysmic future. Yet, unlike his peers, for Blecher the urgency

of Time unfolds with a rigorous diagnostic probity that will not yield to any

unreflecting words. The games of language so beloved by Surrealists are there only

to be disposed of.

Glossing the nonsense conversation he enjoys with a friend:

“What I found in that banter was more than the slightly cloying pleasure of plunging

into mediocrity; it was a vague sense of freedom: I could, for instance, vilify the

doctor to my heart’s content even though I knew—he lived in the

neighborhood—that he went to bed every night at nine . . . We would go on and

on about anything and everything, mixing truth and fancy, until the conversation

took on a kind of airborne independence, fluttering about the room like a curious

bird, and had the bird actually put in an appearance we’d have accepted it as easily

as we accepted the fact that our words had nothing to do with ourselves . . . Back

in the street, I would feel I had emerged from a deep sleep, yet I still seemed to

be dreaming. I was amazed to find people talking seriously to one another. Didn’t

they realize one could talk seriously about anything? Anything and everything?”

This is the “nothing” that is acquiring mass and is already heading for the world

that Blecher feels becoming nothing but the mere traces of a once “serious” life. In

the unfolding researches of his childhood, he has time to uncover in dusty attics

the faded remains of gone worlds: letters, photographs, and paintings more

substantial than the present, which evanesces as he writes, “like a scene viewed

through the wrong side of a binocular, perfect in every detail but tiny and far

off.”

There is an inverted nostalgia here, a nostalgia for the present that has already

taken hold of the writer who is composing both his own and his decade’s epitaph.

Blecher, like Proust, endows places and objects from the past with the ability to

project an independent existence more real than the present. This world hides

another, open only to the genius of child-wonder and adolescent desire.

Adventures in Immediate Irreality

is not a memoir, a novel, or a poem,

though it has been called all those names, and compared rightly with the works of

Proust and Kafka. Blecher belongs in that company for the density and lyrical force

of his writing, but he is also a recording diagnostician of a type the twentieth

century had not yet fully birthed, but the twenty-first is honoring in the highest

degree.

The place of these “adventures” is probably Roman, the provincial Romanian city where

he was born in 1909, a place small enough to explore, and conventional enough to

grasp. The time is childhood and adolescence in the still new twentieth century. The

probing instrument is his body rushing to work for as long as the liberty of his age

and his vitality allow. Blecher didn’t outlive his unfettered genius. In 1928, while

still in medical school in Paris, he was diagnosed with spinal tuberculosis. He was

treated at sanatoriums in Berck-sur-Mer in France, Leysin in Switzerland, and

Techirghiol in Romania. For the last ten years of his life, he was confined to bed,

immobilized by the disease. Despite his condition, he wrote and published his first

piece in 1930, a short story called “Herrant” in Tudor Arghezi’s literary magazine

Bilete de papagal

, contributed to André Breton’s literary review

Le

Surréalisme au service de la révolution

and corresponded with Breton, André

Gide, Martin Heidegger, Ilarie Voronca, Geo Bogza, and Mihail Sebastian. In 1934, he

published

Corp transparent

, a volume of poetry. In 1935, he was moved to a

house on the outskirts of Roman where he wrote and published his major works,

Întâmplări în irealitate imediată

(Adventures in Immediate Irreality)

and

Inimi cicatrizate

(Scarred Hearts), as well as short prose pieces,

articles, and translations. In 1938 he died, at the age of twenty-eight.

Blecher’s genius is also the genius of his disease, and the timing of his death: “I

envied the people around me who are hermetically sealed inside their secrets and

isolated from the tyranny of objects. They may live out their lives as prisoners of

their overcoats, but nothing external can terrorize or overcome them, nothing can

penetrate their marvelous prisons. I had nothing to separate me from the world:

everything around me invaded from head to toe; my skin might as well have been a

sieve. The attention I paid to my surroundings, nebulous though it was, was not

simply an act of will: the world, as is its nature, sank its tentacles into me; I

was penetrated by the hydra’s myriad arms. Exasperating as it was, I was forced to

admit that I lived in the world I saw around me; there was nothing for it.” Those

“hermetically sealed” people, in their healthy bodies and apparently fortunate

longevity, were going to go on living in the coming decade. Max Blecher, whom

nothing separated from the world, had the good luck to die in 1938, freed into the

“outside” before the 1940s.

Vizuina luminată: Jurnal de sanatoriu

(The

Lit-Up Burrow: Sanatorium Journal) was published posthumously in part in 1947 and in

full in 1971. Beginning in the mid-1970s his books were translated into French,

German, Spanish, Czech, Hungarian, Dutch, Swedish, Italian, Polish, and English. The

twenty-first century is even more wildly receptive to Max Blecher.

“For a moment I had the feeling of existing only in the photograph.” Max Blecher

wrote this sentence while Roman Vishniac was capturing a multitude whose members

ceased to exist soon after he photographed them. Those images of people, whose

provincialism was nearly absolute, later toured the world. This sentence by Blecher

resonated for Walter Benjamin, himself in the grip of reproductive

extinction—what the twentieth century already had inscribed in its DNA. It is

a fountain-sentence, a

boca de leone

from which reality spews the bile of

immediate irreality. The magnificent paragraph that opens with that sentence, rests

on another photograph, a Victorian portrait taken at a fair, of the photographer’s

dead child, and concludes with the century’s epitaph: “At fairs, therefore, even

death took on sham, nostalgic-ridden backdrops, as if the fair were a world of its

own, its purpose being to illustrate the boundless melancholy of artificial

ornamentation from the beginning of a life to its end as exemplified by the pallid

lives lived in the waxworks’ sifted light or in the otherworldly beauty of the

photographer’s infinite panoramas. Thus for me the fair was a desert island awash in

sad haloes similar to the nebulous yet limpid world into which my childhood crises

plunged me.”

Blecher foresaw the irreality of the “real” world and the substance of “irreality,”

now main quandaries of our time as we struggle between the “real” and the “virtual.”

“One day the cinema caught fire. The film tore and immediately went up in flames,

which for several seconds raged on the screen like a filmed warning that the place

was on fire as well as a logical continuation of the medium’s mission to give the

news, which mission it was now carrying out to perfection by reporting the latest

and most exciting event in town: its own combustion. Cries of ‘Fire! Fire!’ broke

out all over the room like revolver shots. In no time there was such a racket that

the audience, until then seated quietly in the dark, seemed to have been storing up

great wailing and ululation, like batteries, silent and inoffensive unless suddenly

overcharged and then explosive.”

When hyper-realist ultra-hearing is so acutely accurate it becomes a timeless

metaphor: “And suddenly a clicking noise rang out. It was neither the grate of sheet

metal nor the far-off jangle of a bunch of keys nor the rasp of a motor; it was the

click—easily discernable amidst the myriad everyday sounds—of the wheel

of fortune.”

Like the fair, Blecher’s world is still a world in good order, loosely tethered to

the nineteenth century’s long fin-de-siecle with its tendencies to dematerialize,

slip away, and turn illegible. The educated classes of his time, who thought that

“being illegible” was the greatest threat facing the human race, had no idea what a

colossal loss of order was around the corner: the world and its humans would soon

become illegible, unintelligible, irreparable. But Blecher’s senses saw far. He

grasped the incoming scrambled text of matter, tuned to the disintegration of his

body. The “adventures” of his evanescence are suspenseful, like those in a novel,

beautiful like passages from a European, pessimistic Whitman, a Whitman

à

rebours

, who is not Baudelaire, and these adventures are also news, our

news.

There is no trace of God. But there is an ecstasy in knowing mud. And wonder at the

fact that the world is

full

: “I was surrounded by hard, fixed matter on all

sides—here in the form of balls and sculptures, outside in the form of trees,

houses, and stone. Vast and willful, it held me in its thrall from head to foot. No

matter where my thoughts led me, I was surrounded by matter, from my clothes to

streams in the woods running through walls, rocks, glass . . . I met hay carts and,

now and then, extraordinary things, like a man in the rain carrying a chandelier

with crystal ornaments that sounded like a symphony of hand bells on his back while

heavy drops of rain dripped down the shiny facets. It made me wonder what

constitutes the gravity of the world.”

It is the question that Michael Henry Heim—the great translator who brought

into English some of Central Europe’s finest writers—heard in his own body.

Heim was himself ill when he translated Blecher, for the sake of whom he learned

Romanian. This translation is a special event in the complex geography of

literature: it represents the meeting of a young Romanian genius racing the imminent

destruction of his body, with Michael Heim, a master of the superb English sentence.

Heim’s translation of Blecher’s

Adventures in Irreality

vibrates in tune

with the mysterious filaments of death connecting them in this text. This is why,

despite two decent previous translations into English, Heim’s

Adventures in

Immediate Irreality

is definitive.

ANDREI CODRESCU