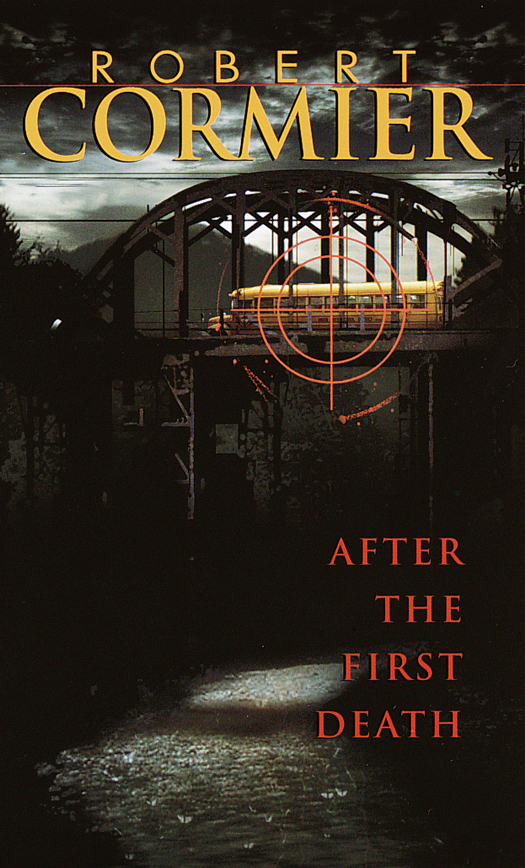

After the First Death

Read After the First Death Online

Authors: Robert Cormier

After the First Death

Beyond the Chocolate War

The Bumblebee Flies Anyway

The Chocolate War

8 Plus 1

Fade

Frenchtown Summer

Heroes

I Am the Cheese

In the Middle of the Night

The Rag and Bone Shop

Tenderness

Tunes for Bears to Dance To

We All Fall Down

Published by

Dell Laurel-Leaf

an imprint of

Random House Children’s Books

a division of Random House, Inc.

Inscription on the quotation page is from “A Refusal to Mourn the Death, by Fire, of a Child in London” from

The Poems of Dylan Thomas.

Copyright 1945 by the Trustees for the Copyrights of Dylan Thomas. Reprinted by permission of New Directions and J. M. Dent & Sons, Ltd., and the Trustees for the Copyrights of the late Dylan Thomas.

Text copyright © 1979 by Robert Cormier

Cover illustration copyright © by Victor Stabin

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the written permission of the Publisher, except where permitted by law. For information address Pantheon Books, New York, New York.

The trademark Laurel-Leaf Library

®

is registered in the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office.

The trademark Dell

®

is registered in the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office.

Visit us on the Web!

www.randomhouse.com/teens

Educators and librarians, for a variety of teaching tools, visit us at

www.randomhouse.com/teachers

eISBN: 978-0-307-83424-9

RL: 6.2

v3.1

to my daughter Renée

with love

After the first death,

there is no other.

DYLAN THOMAS

1

1I keep

thinking that I have a tunnel in my chest. The path the bullet took, burrowing through the flesh and sinew and whatever muscle the bullet encountered (I am not the macho-muscled type, not at five eleven and one hundred eighteen pounds). Anyway, the bullet went through my chest and out again. The wound has healed and there is no pain. The two ends of the tunnel are closed although there’s a puckering of the skin at both ends of the tunnel. And a faint redness. The puckering has a distinct design, like the old vaccination scar on my father’s arm. Years from now, the wound will probably hurt the way my father’s old wounds hurt him, the wounds he received in those World War Two battles. My mother always jokes about the wounds: oh, not the wounds themselves but the fact

that he professes to forecast weather by the phantom pains and throbbings in his arms and legs.

Will my wound ache like his when I am his age?

And will I be able to tell when the rain will fall by the pain whistling through the tunnel in my chest?

I am joking, of course, but my joking is entirely different from my mother’s tender jokes.

I am joking because I won’t have stayed around to become a human barometer or an instrument capable of forecasting weather.

But—who’s the joke on?

The first of many questions about my presence here.

Keep a scorecard handy.

My father is scheduled to visit me today.

His first visit since the Bus and the Bridge last summer.

I am typing this in the room at Castle and it’s beautiful here as I write this. Through the window, I can see the quadrangle and the guys indulging in a snowball fight. The first snowfall of the season. The snow is late this year. Christmas is only two weeks away. Thanksgiving was dry and cold with a pale sun in the sky but no wind. Perfect for a football game, the traditional game between Castle and Rushing Academy. Castle won, 21 to 6, and there was a big celebration on campus. Elliot Martingale brought these fireworks back from summer vacation; they were left over from July 4th at his family’s place on Cape Cod, and he said they would be touched off when we won the big game on Thanksgiving Day. We won, he set them off. Beautiful. That’s when I went to the john, swallowed fourteen

sleeping pills, lay down on the bed listening to the cherry bombs explode and then a cluster of firecrackers going off like a miniature machine gun; and it was nice lying there, drifting away, and then I thought of the kids on the bus, strewn around like broken toys while the guns went off, and I started getting sick and rushed off to the bathroom to vomit.

Please do not consider these the notes of a self-pitying freak who needs the services of a psychiatrist.

I am not filled with pity for myself. And I’m not writing this to cop a plea of some kind.

I do not consider this a suicide note either.

Or even a prelude to one.

When the time comes to perform the act, I will do it without any prelude or prologue, and may simply walk up River Road one afternoon, arrive at Brimmler’s Bridge, calmly climb the parapet or whatever it’s called, and let myself plummet to the riverbed below.

I have deduced, reflecting on the Bus, that this would be the best way to shuffle off this mortal coil. Poetic justice, you see. Perhaps that’s what I should have done when I was sent out to the Bus. The Bus was also on a bridge. That’s when I should have taken the plunge, the dive, or the leap. The Bridge on which the Bus was perched is even higher than Brimmler’s Bridge. Just think how I would have saved the day—and myself—that way.

And my father most of all.

But how many times is a person allowed to die?

Anyway, my parents are scheduled to arrive here late this morning.

Eleven o’clock to be exact.

My father’s first visit since the Bus and the Bridge, but I already said that, didn’t I?

My mother has been faithful about visiting. My mother is kind and witty and stylish. She is the essence of the loving wife and mother. She has such amazing strength, an inner strength that has nothing to do with the flexing of muscles. I always sensed it, even as a kid. My father has strength, too. But he has always been too shadowy to pin down. The nature of his profession, I realize now. His is the kind of profession that not only disguises the man but consumes him as well. And his family, too. Even my mother, with all her strength.

When she visited me the first time in September only a few days after my arrival, she played it cool and calm, and this is just what I needed.

“Do you want to talk about it, Mark?” she asked.

My name is Ben, my father’s name is Mark. If it had been anyone but her, I would have called it a Freudian slip. But she is too uncomplicated for that kind of thing.

I wondered how much she knew about what happened on the bridge. “I’d rather not talk about it,” I said. “Not just yet.”

“Fine,” she said, matter-of-factly, settling down for the visit, arranging her dress over her knees. She has beautiful legs and she is utterly feminine. She never wears slacks or pants suits, always skirts or dresses, even when she does housecleaning. She asked me about school and the classes and the guys, and I told her, talking mechanically, as if my mouth had nothing to do with the rest of my body. I told her about Mr. Chatham, who is my math teacher and might have taught my father a generation ago. This is one of the benefits of attending your father’s alma mater, my mother said, when she drove me up here last fall. She said I would be

able to gather new insights on my father. I didn’t tell her that Mr. Chatham is practically senile, the butt of a thousand boyish and not-so-boyish pranks and jokes, and that he didn’t remember my father at all. I had suggested the possibility to him. “My name is Ben Marchand,” I’d told him, “and my father came to Castle back before World War Two—do you remember him?”

“Of course, dear boy,” he said, “of course.”

But I did not believe him. His eyes were glazed and vacant, his hand shook, and he always seems about to leap out of harm’s way. Which is reflex action. Guys like Elliot Martingale and Biff Donateli rejoice in making old Chatham’s last days lively. We keep him on his toes, keep him sharp, keep him from dropping into complete senility, Elliot says. How can a man drop out when he thinks a cherry bomb’s going to go off in his pants any minute?

Anyway, I started to lie to my mother about Mr. Chatham and his nonexistent memories of my father. “He remembers Dad as a good student,” I said. “Serious. Never fooled around much in class. A shy, sensitive lad: those were his exact words.” I tried to imitate Mr. Chatham’s rusty old voice: “A little too thin for his height, lad, but you could see he would fill out someday and be an outstanding man.”

I could see immediately that she didn’t believe me. She has many admirable qualities but she would never succeed as an actress. The disbelief was apparent in her eyes and in the expression on her face.

“Isn’t Dad sensitive and wasn’t he a good student?” I asked. “He must have been. He’s a general now, isn’t he?”

“You know your father doesn’t like to be called a general,” she said.

“True,” I said, and felt myself drifting away from her, something I have been doing recently, drifting away while standing still, letting myself go as if the world is a huge blotter and I am being absorbed by it. “But he is a general, isn’t he?” I asked, persisting, suddenly not wanting to drift away, not at this particular moment, wanting to make a point. What point?

And then my mother’s strength asserted itself. “Ben,” she said, her voice like the snapping of a tree branch. It reminded me of old movies on television where someone is screaming hysterically and someone else slaps the screamer and the hysterics die down. Well, I wasn’t screaming hysterically but I must admit that I was hysterical all right. You can be hysterical without screaming or ranting and raving, or hitting your head against a wall. You can be quietly hysterical sitting in a dorm talking to your mother, watching the September sun climbing the wall like a ladder as it filters in through a sagging shutter. And the slap doesn’t have to be a physical act; it can be one word,

Ben

, your own name lashing out. Yet she did it with love. I have always been assured of her love. And even as I responded to her shouted

Ben

, snapping me back from the drifting, I still said to myself: But he is a goddam general, whether he likes it or not, and that’s why I’m here.