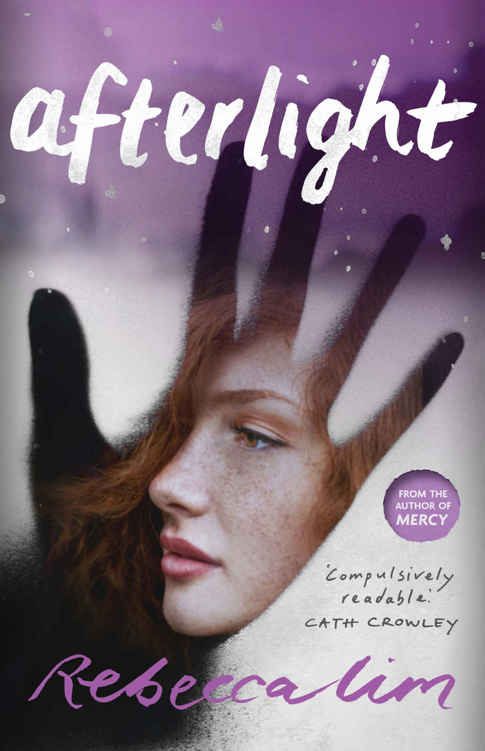

Afterlight

Authors: Rebecca Lim

PRAISE FOR REBECCA LIM

‘

The Astrologer’s Daughter

is compulsively readable. Avicenna is a captivating hero—tough

yet vulnerable. This gritty and mysterious love story will stay with me for a long

time.’ Cath Crowley

‘Smart and original—a beautifully written mash-up of mystery, thriller and love story.’

Vikki Wakefield

‘[Lim’s] taut, assured thriller weaves together astrology and mythology, poetry and

poverty…Teen and adult readers who like their mysteries gritty and literary, with

a touch of magic: seek this one out.’

Kirkus Reviews

(Starred)

‘A perfect balance of wit, humour, willpower and raw emotion.’

Dolly

‘The best aspect of this novel was Avicenna herself… a captivating combination of

brazen and terrified.’

Launceston Examiner

‘Subtly beautiful and utterly intriguing, Rebecca Lim’s Mercy series brims with mystery

and romance that pulls readers through the veil between worlds real and mythical.’

Andrea Cremer,

New York Times-

bestselling author of

The Nightshade Series

‘Gripping. By the end, you can’t help but wonder who this angel of Mercy will become

next.’

Sunday Herald Sun

‘What is compelling about this novel is not only its tightly constructed plot but

the lyrical quality of the writing… Not to be missed.’

Reading Time

Rebecca Lim is a writer and illustrator based in Melbourne, Australia. She worked

as a commercial lawyer for several years before leaving to write full time. Rebecca

is the author of sixteen books for children and young adult readers, including

The

Astrologer’s Daughter

. An Aurealis Awards finalist, Rebecca’s work has been longlisted

for the Davitt Award for YA, the Gold Inky Award and the CBCA Book of the Year Award

for Older Readers. Her novels have been translated into German, French, Turkish,

Portuguese and Polish.

The Text Publishing Company

Swann House

22 William Street

Melbourne Victoria 3000

Australia

Copyright © Rebecca Lim 2015

The moral rights of Rebecca Lim have been asserted.

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright above, no part of

this publication shall be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system,

or transmitted in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying,

recording or otherwise), without the prior permission of both the copyright owner

and the publisher of this book.

First published in 2015 by The Text Publishing Company

Cover and page design by Imogen Stubbs

Cover photographs: hand © Lia & Fahad / Stocksy United,

face © Maja Topčagić / Stocksy United

Typeset by J&M Typesetting

National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry:

Author: Lim, Rebecca (Rebecca Pec Ca), 1972-

Title: Afterlight / by Rebecca Lim.

ISBN: 9781925240498 (paperback)

ISBN: 9781922253255 (ebook)

Dewey Number: A823.4

This project has been assisted by the Commonwealth Government through the Australia

Council, its arts funding and advisory body.

To the people in my lifeboat:

Michael, Oscar, Leni and Yve.

With love always.

I have been one acquainted with the night.

I have walked out in rain—and back in

rain.

I have outwalked the furthest city light.

ROBERT FROST (1928)

Contents

I used to believe in ghosts.

I saw something, once. It’s not anything I’ve ever shared with anyone. I was little

and he was real and it was dark and he only stood over me that one time when I was,

maybe, five?

A tall man with a mass of long, pale hair, tied into a ragged plait. Sinewy and broad-shouldered,

wearing a plaid shirt, jeans and boots. Heavy chains of silver at his throat and

on his wrists. I could see all that, even with the light out.

But he was

real

. Real as you. And I was terrified. But all he did was look down at

me, lying with my blankets pulled right up to my eyes, looking back up at him.

Then I breathed in—just a trembly, choky flutter, the tiniest sound—and he was gone.

But I don’t believe, not anymore. Because if ghosts were real, Mum and Dad would

have found a way—some way—to make it back to me. They promised me they’d always be

there. There wasn’t a day when they didn’t say they loved me and we’d grow old together

and they’d be there to look after all my babies while I took on the world, because

the world was my oyster, I could be anything and do anything, I was better than them—which,

based on my track record with boys and school, was never going to happen.

But they were optimists. It used to disgust me how much they looked on the bright

side of life because before I came along, they said, life had never been bright.

It had been hopeless. But I’d saved them. That was the word Mum had used:

Saved

.

They’d been through the wars, Dad used to remark.

Which means that me and your Mum

are gonna live forever, Sophie. You’ll never be rid of us.

So when they were T-boned on the way up to Gippsland on Dad’s Harley—taken out by

an off-his-face random driving a stolen car—I expected…something. A miracle. At least

a sign. Just a

Yoo hoo, love, we’re okay

.

But there was no sign. Just a couple of matching white coffins a few days later,

and a wake at my Grandma’s

pub that lasted for three days. Big bruisers in tatts

and leather and Cuban-heeled boots from all over the country with names like Flasher

and Fat Arse coming up to me all beery-breathed and teary-eyed, putting their meaty

hands on my shoulders and giving them a squeeze, saying, ‘Brother-in-arms, good man,

the best.’

They were, though—the best dad and mum in the world, Joss and Angel. More like a

couple of daggy, embarrassing friends than parents. No expectations, no bullshit;

all love. And then, just like that—because of an old-times-sake Sunday motor up to

the Lakes for a feel of the wind in their hair—the world no longer contained them.

Around here, we’ve always been

those Teagues who live down the pub

.

So after Dad and Mum died, I just kept on living at Gran’s place—The Star Hotel—the

way I’ve always lived there. Life involved the same bedroom, the same clothes, the

same school and the same pervasive smell of beer. Only, someone had taken a God-sized

eraser to part of it. They were taken from me in the November before my final year

was due to kick off. They died before I’d finally be old enough to vote or drink.

It felt like the cruellest, most irreversible joke.

It also felt unreal for the first few months. Like I’d open the storeroom door and

Dad might be standing there with his back to me, stacking bulk lots of toilet rolls.

Or I’d take out the garbage and somehow catch Mum sneaking a cigarette in the laneway

behind the pub.

It made me a little crazy. I’d sit for hours inside the built-in wardrobe in their

bedroom, just so that the air would smell of them. I’d talk to complete strangers

at random hoping they’d ask me how I was and then spring my tragic story on them

only to watch those same people run away in horror. I cried in public places and

walked the streets around The Star after dark, practically begging to be murdered

because the dark was

where they were

; they were nowhere in the light.

For a while, I convinced myself they were just on the round-the-world cruise Mum

had always wanted to go on—only they’d forgotten to send me postcards. And craziest

of all? I walked up to Floyd Parker the first week that school was back and kissed

him on the mouth in front of actual witnesses, for seconds that felt like hours.

I had a death wish, obviously. Life was short, it had been proven, and if I never

did it, I’d never do it. Now, now was the time. There was nothing left to lose.

Stick legs and hair, that’s what I was known for. Hair like that

L’Oreal

bird, the

old one, not Beyoncé or Eva or Doutzen. A curly, ginger cloud, so thick and crazy

it

looked too big for my head. And freckles—I only had to step out into the light

for a new infestation to start somewhere. I was already 183.5 centimetres without

shoes on and in possession of hair-trigger blood vessels in the face. No meat on

me to speak of. All bones and angles.

So I deserved the ensuing hilarity. Floyd Parker had lived across the road, six doors

down, for years and years. We’d even walked in to school together; I couldn’t count

how many times. But he’d never shown me anything other than benevolent disinterest,

a fact I recklessly disregarded when I pulled him to me. He was hot—only growing

hotter—and I was a mess. What I’d done was completely mental. Like a lemming, I’d

thrown myself at him and he’d side-stepped and let me go over the cliff.