Against the Gods: The Remarkable Story of Risk (40 page)

Read Against the Gods: The Remarkable Story of Risk Online

Authors: Peter L. Bernstein

In practice, insurance is available only when the Law of Large

Numbers is observed. The law requires that the risks insured must be

both large in number and independent of one another, like successive

deals in a game of poker.

"Independent" means several things: it means that the cause of a

fire, for example, must be independent of the actions of the policyholder. It also means that the risks insured must not be interrelated, like

the probable movement of any one stock at a time when the whole

stock market is taking a nose dive, or the destruction caused by a war.

Finally, it means that insurance will be available only when there is a

rational way to calculate the odds of loss, a restriction that rules out

insurance that a new dress style will be a smashing success or that the

nation will be at war at some point in the next ten years.

Consequently, the number of risks that can be insured against is far

smaller than the number of risks we take in the course of a lifetime. We

often face the possibility that we will make the wrong choice and end

up regretting it. The premium we pay the insurance company is only

one of many certain costs we incur in order to avoid the possibility of a larger, uncertain loss, and we go to great lengths to protect ourselves

from the consequences of being wrong. Keynes once asked, "[Why]

should anyone outside a lunatic asylum wish to hold money as a store

of wealth?" His answer: "The possession of actual money lulls our disquietude; and the premium we require to make us part with money is

the measure of our disquietude."17

In business, we seal a deal by signing a contract or by shaking hands.

These formalities prescribe our future behavior even if conditions

change in such a way that we wish we had made different arrangements. At the same time, they protect us from being harmed by the

people on the other side of the deal. Firms that produce goods with

volatile prices, such as wheat or gold, protect themselves from loss by

entering into commodity futures contracts, which enable them to sell

their output even before they have produced it. They pass up the possibility of selling later at a higher price in order to avoid uncertainty

about the price they will receive.

In 1971, Kenneth Arrow, in association with fellow economist

Frank Hahn, pointed up the relationships between money, contracts,

and uncertainty. Contracts would not be written in money terms "if

we consider an economy without a past or a future."18 But the past

and the future are to the economy what woof and warp are to a fabric. We make no decision without reference to a past that we understand with some degree of certainty and to a future about which we

have no certain knowledge. Contracts and liquidity protect us from

unwelcome consequences even when we are coping with Arrow's

clouds of vagueness.

Some people guard against uncertain outcomes in other ways. They

call a limousine service to avoid the uncertainty of riding in a taxi or

taking public transportation. They have burglar alarm systems installed

in their homes. Reducing uncertainty is a costly business.

Arrow's idea of a "complete market" was based on his sense of the

value of human life. "The basic element in my view of the good society," he wrote, "is the centrality of others.... These principles imply

a general commitment to freedom.... Improving economic status and

opportunity ... is a basic component of increasing freedom. `9 But the fear of loss sometimes constrains our choices. That is why Arrow applauds insurance and risk-sharing devices like commodity futures contracts and public markets for stocks and bonds. Such facilities encourage investors to hold diversified portfolios instead of putting all their eggs in one basket.

There is a huge gap between Laplace and Poincare on the one hand and Arrow and his contemporaries on the other. After the catastrophe of the First World War, the dream vanished that some day human beings would know everything they needed to know and that certainty would replace uncertainty. Instead, the explosion of knowledge over the years has served only to make life more uncertain and the world more difficult to understand.

Seen in this light, Arrow is the most modem of the characters in our story so far. Arrow's focus is not on how probability works or how observations regress to the mean. Rather, he focuses on how we make decisions under conditions of uncertainty and how we live with the decisions we have made. He has brought us to the point where we can take a more systematic look at how people tread the path between risks to be faced and risks to be taken. The authors of the Port-Royal Logic and Daniel Bernoulli both sensed what lines of analysis in the field of risk might lie ahead, but Arrow is the father of the concept of risk management as an explicit form of practical art.

The recognition of risk management as a practical art rests on a simple cliche with the most profound consequences: when our world was created, nobody remembered to include certainty. We are never certain;

we are always ignorant to some degree. Much of the information we have

is either incorrect or incomplete.

Suppose a stranger invites you to bet on coin-tossing. She assures

you that the coin she hands you can be trusted. How do you know

whether she is telling the truth? You decide to test the coin by tossing

it ten times before you agree to play.

When it comes up eight heads and two tails, you say it must be

loaded. The stranger hands you a statistics book, which says that this

lop-sided result may occur about one out of every nine times in tests of

ten tosses each.

Though chastened, you invoke the teachings of Jacob Bernoulli

and request sufficient time to give the coin a hundred tosses. It comes

up heads eighty times! The statistics book tells you that the probability

of getting eighty heads in a hundred tosses is so slight that you will have

to count the number of zeroes following the decimal point. The probability is about one in a billion.

Yet you are still not 100% certain that the coin is loaded. Nor will

you ever be 100% certain, even if you were to go on tossing it for a

hundred years. One chance in a billion ought to be enough to convince

you that this is a dangerous partner to play games with, but the possibility remains that you are doing the woman an injustice. Socrates said

that likeness to truth is not truth, and Jacob Bernoulli insisted that

moral certainty is less than certainty.

Under conditions of uncertainty, the choice is not between rejecting a hypothesis and accepting it, but between reject and not-reject.

You can decide that the probability that you are wrong is so small that

you should not reject the hypothesis. You can decide that the probability that you are wrong is so large that you should reject the hypothesis.

But with any probability short of zero that you are wrong-certainty

rather than uncertainty-you cannot accept a hypothesis.

This powerful notion separates most valid scientific research from

hokum. To be valid, hypotheses must be subject to falsification-that

is, they must be testable in such fashion that the alternative between

reject and not-reject is clear and specific and that the probability is

measurable. The statement "He is a nice man" is too vague to be

testable. The statement "That man does not eat chocolate after every

meal" is falsifiable in the sense that we can gather evidence to show whether the man has or has not eaten chocolate after every meal in the

past. If the evidence covers only a week, the probability that we could

reject the hypothesis (we doubt that he does not eat chocolate after

every meal) will be higher than if the evidence covers a year. The result

of the test will be not-reject if no evidence of regular consumption of

chocolate is available. But even if the lack of evidence extends over a

long period of time, we cannot say with certainty that the man will

never start eating chocolate after every meal in the future. Unless we

have spent every single minute of his life with him, we could never be

certain that he has not eaten chocolate regularly in the past.

Criminal trials provide a useful example of this principle. Under our

system of law, criminal defendants do not have to prove their innocence; there is no such thing as a verdict of innocence. Instead, the hypothesis to be established is that the defendant is guilty, and the prosecution's

job is to persuade the members of jury that they should not reject the

hypothesis of guilt. The goal of the defense is simply to persuade the jury

that sufficient doubt surrounds the prosecution's case to justify rejecting

that hypothesis. That is why the verdict delivered by juries is either

"guilty" or "not guilty."

The jury room is not the only place where the testing of a hypothesis leads to intense debate over the degree of uncertainty that would

justify rejecting it. That degree of uncertainty is not prescribed. In the

end, we must arrive at a subjective decision on how much uncertainty

is acceptable before we make up our minds.

For example, managers of mutual funds face two kinds of risk. The

first is the obvious risk of poor performance. The second is the risk of

failing to measure up to some benchmark that is known to potential

investors.

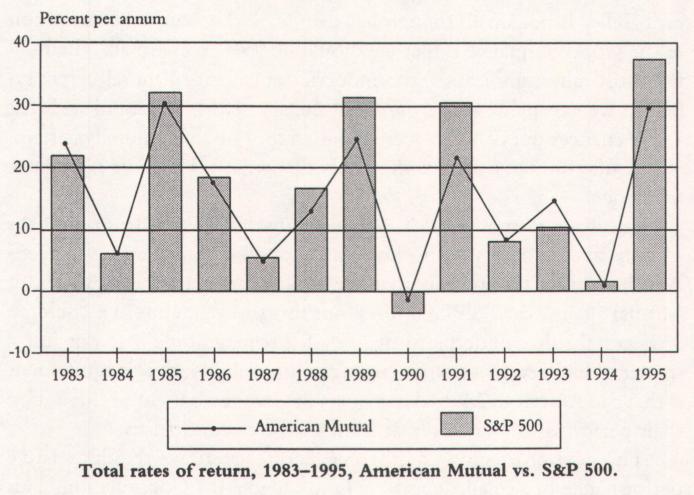

The accompanying chart20 shows the total annual pretax rate of

return (dividends paid plus price change) from 1983 through 1995 to

a stockholder in the American Mutual Fund, one of the oldest and

largest equity mutual funds in the business. The American Mutual performance is plotted as a line with dots, and the performance of the

Standard & Poor's Composite Index of 500 Stocks is represented by

the bars.

Although American Mutual tracks the S&P 500 closely, it had

higher returns in only three out of the thirteen years-in 1983 and

1993, when American Mutual rose by more, and in 1990, when it fell

by less. In ten years, American Mutual did about the same as or earned

less than the S&P.