Agnes Strickland's Queens of England (35 page)

Read Agnes Strickland's Queens of England Online

Authors: 1796-1874 Agnes Strickland,1794-1875 Elizabeth Strickland,Rosalie Kaufman

Tags: #Queens -- Great Britain

Shortly after her recovery. Princess Anne asked permission of her father to spend a few weeks at the Hague. The Prince of Denmark, her husband, was going on a visit to his native land, and it was his wife's plan that she should be conducted by him to her sister's court, there to remain

until his return. Her confidential friend, Lady Churchill, was to accompany her. But King James had begun to see something of the part his children were playing against him, and peremptorily refused to allow Anne to leave England. In a fit of temper at being thus opposed she retired to Bath, where she remained until after the birth of her brother, whose appearance in the world was most unwelcome to both her and Mary of Orange.

Meanwhile aiifairs had taken such a turn that King James's downfall was rapidly approaching. His adherence to the Catholic cause deprived him of support from the Reformed church, and obliged some of the best and most loyal of his subjects to stand by and witness his ruin, though with intense pain, because they were unable to stir hand or foot in his behalf.

Lord Clarendon, who had by this time returned to London from the Hague, was one of these. It will be remembered that he was Knig James's brother-in law, and a warm friendship had always existed between the two men. It was most painful to him to observe the indifiference of Anne towards her father, particularly when reports reached England that the Prince of Orange was coming over with an army to mvade the country. Clarendon questioned the princess to find out how much she knew of the matter, but could get very little satisfaction, for she evaded him as much as possible, and pretended to have no information but that which her husband had received from the king himself. After several vain attempts to induce his niece to speak to her father and endeavor to console him, — for he had sunken into a most painful state of melancholy, — Lord Clarendon begged her at least to urge the king to consult with some of his old friends, each and all of whom were warmly attached to him. But this unnatural daughter put him off, and preferred to increase her father's anguish.

One day in October there was a royal leve'e at Whitehall. The king was in a painfully depressed state of mind, and told Lord Clarendon that the Prince of Orange had embarked with his Dutch troops, and only awaited a favorable wind to sail, adding, " I have nothing by this day's post from my daughter Mary; and it is the first time I have missed hearing from her for a long while."

The unfortunate father never heard from her again.

Lord Clarendon made another attempt to induce Anne to save her father, which she might have.done if she had chosen ; but she did not, and treated every proposition with disgusting levity.

Louis XIV. offere to intercept the Dutch fleet; but James declined his aid, because of the confidence he felt in his daughter Mary. Her last letter assured him that the prince's fleet was made ready to repel an attack of the French, which was hourly expected ; and the fond, confiding father believed her.

It was Dr. Burnet, a well-known author and minister, who undertook to explain to the Princess of Orange all the details of the political situation ; and after the prince decided to get possession of the throne of Great Britain, he asked her what would be her husband's position, she being the heir and not he.

She replied that she had not considered that point, but would be obliged to him if he would tell her. Burnet, who was evidently acting in the interest of the prince, replied, " That she must be contented as a wife to engage in her husband's interest and give him the real authority as soon as it came into her hands." Mary consented, and asked the doctor to bring the prince to her that she might assure him of her submission to his will. William was hunting that day; but on the moirovv, after informing him of the conversation with the princess, Burnet conducted him to her presence.

Mary told him that she was surprised to hear from the doctor how, by the laws of England, a husband could be made subservient to his wife, providing the title of king came to him through her; and added a solemn promise that she should always be obedient to him, and that he should rule, not she. It seems surprising that so faithless a daughter should have been so dutiful a wife; but the prince had broken her spirit by his frequent acts of cruelty and neglect, and she was as submissive as a whipped cur.

Instead of thanking his wife, William treated her decision as a matter of course, and merely answered with a grunt of satisfaction, giving Dr. Burnet great credit for the persuasive eloquence that had brought about so favorable a result.

In October the Prince of Orange sailed with a fleet of fifty-two ships of war; and, after a very stormy voyage, landed at an English village on the anniversary of the Gunpowder Plot.

Meeting with no opposition, he marched four miles into Devonshire, followed by his entire force. The prince knew what a risk he was taking, and waited with breathless anxiety to see how many of the west of pjigland people would flock to his standard.

He published a declaration that the Prince of Wales was not the real child of James II.; but that a strange baby had been adopted to impose on the British nation, who was to rule them as a Roman Catholic. This was done to prevent the country from educating the prince according to the doctrines of .the Church of England, which would probably have established his succession. Of course a child upon whose birth any doubt was cast could never rule as a Catholic, nor be educated by the state for any purpose; therefore the daughters of James II. pretended to

believe the falsehood, knowing that in the event of the prince's accession they would stand no chance of ever wearing the crown.

News arrived in London that Lord Cornbury, eldest son of the Earl of Clarendon, had deserted the king's army with three regiments, and gone over to the enemy. Clarendon was overcome with grief and shame at such conduct on the part of one of his flesh and blood. When Princess Anne saw him she asked why he had not been to see her for several days. He replied, " that he was so much concerned for the villany his son had committed that he was ashamed of being seen anywhere."

"Oh," replied the princess, "people are so apprehensive of popery that you will find many more of the army will do the same."

And she was right; for desertions became of daily occurrence, and King James was surrounded by traitors on all sides. Anne knew of Lord Cornbury's intended desertion, and was anxiously awaiting news from her husband, who, with a display of affection and sincerity, had gone off with her father to assist in defending him against the Prince of Orange. Lord Churchill and Sir George Hewett were with the king also; and these two were concerned in a plot against the life of their sovereign, which the latter confessed on his deathbed some years later.

Every time the king heard that one of his officers had gone over to the enemy. Prince George of Denmark would raise his eyes and hands with affected surprise, and exclaim, " Is it possible ! " At last, after supping with the king and speaking in terms of abhorrence of all deserters, the prince, Churchill, and Hewett, taking advantage of an attack of illness that had suddenly seized their sovereign, went off in the night to the hostile camp. When informed of it, James exclaimed: "How? Has 'Is It Possible' gone

off, too ?" Yet this departure was a cruel blow to the father, who said: " After all, I only mind his conduct as connected with my child ; otherwise the loss of a stout trooper would have been greater."

In expectation of her husband's desertion, Anne had made arrangements for her own flight; and no sooner did the news reach her that he had gone than she followed. It was Sunday night, and the princess retired to her room at the usual hour. Mrs. Danvers, the lady-in-waiting, was not in the secret, and went to bed as usual in the ante-chamber. Ladies Fitzharding and Churchill had entered Princess Anne's room early in the evening, and hidden themselves by agreement m her dressing-room. At midnight, accompanied by these two women, the princess stole out of the palace, and met Lord Dorset in St. James's Park, A coach stood in waiting a little distance off; but the rain poured in torrents, and the mud was so deep that Anne lost one of her shoes in a puddle, from which there was neither time nor inclination to extricate it. This little accident was treated as a joke by the adventurers, who laughed heartily, while Lord Dorset gallantly stuck the princess's foot into one of the kid gauntlets he had pulled off; and assisted her to hop forward to the carriage. The party drove to the Bishop of London's house, where they were refreshed and the princess supplied with shoes, and started by daybreak for Lord Dorset's castle in Waltham Forest.

After a few hours' rest they proceeded to Nottingham, where the Earl of Northampton, attired in military uniform, raised a purple standard in the name of the laws and liberties of England, and invited the people to gather around the Protestant heiress to the throne. Afterwards Anne went on to Warwick, where there was a project on foot for the extermination of all the papists in Englapd. Although the princess knew that her father's head would be the first to

fall should such a plan be carried into effect, she was so unnatural as to favor it.

A tremendous uproar was raised when Anne's women-in-waiting entered her room the morning after her flight and found her bed undisturbed and the princess herself missing. Before many minutes the whole court was aroused with the lamentations of the people, who declared that the princess had been murdered by the queen's priests. The storm rose to such a height that a mob collected in the street and swore that the palace should be pulled down, and Mary Beatrice pulled to pieces if Anne were not forthcoming. No doubt the threat would have been put into execution had it not been for the discovery of a letter which the missing princess had left lying on her toilet-table, stating that she had gone off to avoid the king's displeasure on account of her husband's desertion; and that she should remain away until a reconciliation had been effected. " Never was any one," she wrote, " in such an unhappy condition, so divided between duty to a father and a husband; and therefore I know not what I must do but to follow one to preserve the other." This would be all very well if she had been dutiful to her father; but as she had only one week before informed Orange by letter that her husband would soon be with him, ready to serve his cause to the utmost, we can only feel intense disgust at such deceptiorv

CHAPTER XI,

James II. arrived in London just after the excitement caused by Anne's escape had subsided. He had been obliged to leave his army on account of illness, and when he heard of his daughter's conduct, he struck his breast and exclaimed : " God help me! my own children have forsaken me in my distress." From that moment he lost heart and ceased to struggle to retain his crown; but he never censured Anne as he might have done, nor was he aware of the extent of her treachery.

Meanwhile, _Jhe Prince of Orange induced many of the most loyal subjects of the crown to join him by circulating the report that he had come to England for the sole purpose of establishing peace between James II. and his people. So he advanced as far as Henley, and while resting there heard, to his unspeakable joy, that the king had disbanded bis army, and foll(?wed his wife, who, with the Prince of Wales, had escaped to France. They could not more completely have played into his hand.

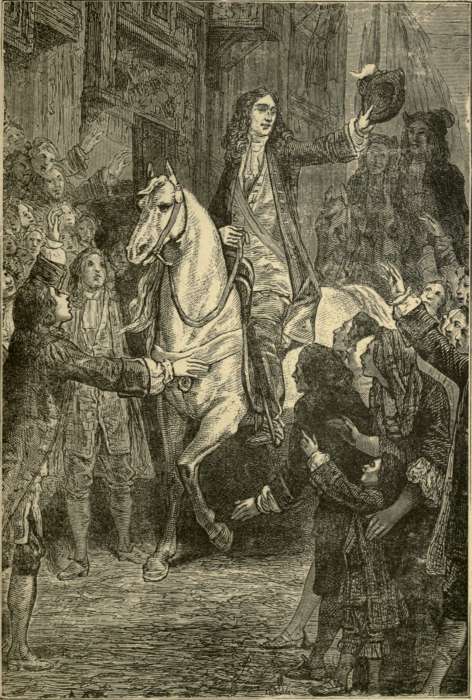

Prince George of Denmark waited for his wife at Oxford, which place she entered with military state, escorted by several thousand mounted gentlemen, who, with their tenants, had joined her followers as she passed through the various counties. Bishop Compton, Anne's early tutor, rode before her in military dress, and carried a purple flag in token of his adherence to her cause.

James had been captured and taken back to Whitehall, so William of Orange stopped at Windsor and sent his Dutch guard forward to expel his uncle; for neither he nor his sister-in-law dared to face the father whom they had so basely injured. The next day the prince entered London quietly, went straight to St. James's Palace, and retired to his bedchamber. In the evening bells rang, guns fired, and there was general rejoicing among the Orange party. A few days later the Prince and Princess of Denmark returned, and took up their abode at the palace they had lived in ever since their marriage, called the Cockpit, because the site of it had once been used for that barbarous amusement.

[A.D. 1689.] Anne felt no regret at the fate that had overtaken her unfortunate father, but triumphantly ap>-peared in public with Lady Churchill, both decked in orange ribbons, an emblem of the cause they had espoused. Her uncle. Lord Clarendon, took her severely to task for not showirg some concern on account of her father's downfall, but she proved very plainly that she felt none ; but it was not many weeks before she regretted having taken sides with William. This was not because of any qualms of conscience, or awakening of affection for her parent, — no, indeed! It was only that her interests were at stake, and her rights in danger of being forfeited * A convention had been called to arrange how the kingdom was to be governed, and as leader of a well-disciplined army of fourteen thousand foreign soldiers, quartered in and about London, the Prince of Orange was likely to have the matter settled just as he chose. The convention were perplexed, however; for though they decided to exclude the Prince of Wales and settle the succession on Mary of Orange, they were by no means willing, in the event of her death, to have the kingdom governed by a foreigner, particularly as his religion