Alex's Wake (20 page)

Authors: Martin Goldsmith

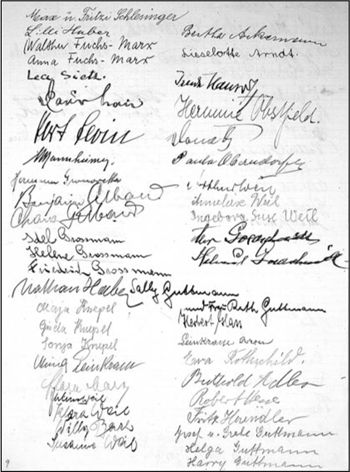

With our deepest respect and sincerest thanks, The Passengers of the

St. Louis

.

Every one of the 907 passengers signed the declaration.

That afternoon Belgian police scuffled with a Nazi-inspired group called the National Youth Organization, an ugly echo of the conditions that had forced the refugees to leave their homeland in the first place. The NYO was protesting the arrival of the

St. Louis

, distributing handbills on which was printed the cheery message: “We, too, want to help the Jews. If they call on our offices each one will receive free of charge a length of rope and a long nail.” After a few minutes of pushing, shoving, and shouting, the police confiscated the handbills and dispersed the crowd.

Later that afternoon, the 214 passengers who were bound for Belgium were served a last meal on board the

St. Louis

, and then shortly after 5 p.m., they began to file slowly off the ship. After more than a month at sea, it was difficult for some of them to believe that they were actually disembarking, and several turned around frequently to wave to those still on board. A woman who was among the most enthusiastic wavers stumbled, fell heavily, and broke her leg. She was picked up by an ambulance and spent her first night on Belgian soil in a hospital. Troper slept that night at Antwerp's Century Hotel. Before retiring, he sent a telegram back to the Joint in New York. “Work distribution 907 passengers completed believe everything OK 300 tons baggage and 5,000 pieces hand luggage going sleep after seventeen consecutive hours most trying ordeal I ever experienced regards Troper.”

A portion of the list of

St. Louis

passenger signatures on the Declaration of Thanks and Gratitude presented to Morris Troper on June 17, 1939. Alex and Helmut's signatures appear in the middle of the right-hand column

.

(Courtesy of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum)

At 5:00 a.m., Sunday, June 18, the 181 refugees who were headed for Holland were awakened and served a last breakfast. A riverboat, the

Jan van Arckel

, pulled alongside the

St. Louis

, and the Dutch contingent, carrying boxes of sandwiches and sweets from the purser, filed off the luxury liner and onto the little steamer. Accompanied by hearty cheers

from the remaining

St. Louis

passengers, the

Jan van Arckel

slowly pulled away at 9:30 to begin her journey through the complex waterway system to Rotterdam. Along the way, she was followed by an escort of police boatsânot unlike her escort out of Havanaâand saluted by hundreds of well-wishers who lined the canals, waving, whistling, and welcoming the wanderers.

That afternoon, Morris Troper, his “trying ordeal” of the previous day ameliorated by a good night's sleep, returned to the

St. Louis

to oversee the final transfer of refugees. The 288 passengers bound for England and the 224, among them Alex and Helmut, accepted by France, would take another HAPAG ship, the

Rhakotis

. A 6,700-ton freighter christened the

San Francisco

when she was built in 1927, she'd been renamed

Rhakotis

in 1935. Outfitted to carry no more than fifty passengers, she was about to be boarded by ten times that many people. Representatives from HAPAG had hastily made preparations; the plan was to sleep men and women separately in double-decker steel bunks both fore and aft, with meals to be served at long tables amidships.

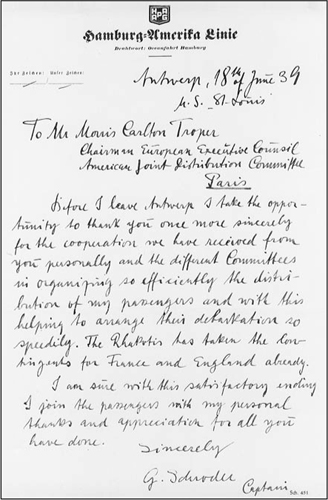

Boarding began mid-afternoon on Sunday, and shortly before 4:00 the

Rhakotis

, now filled with its new human cargo, was towed upstream. The Antwerp port authority had ruled that she could not spend the night in the vicinity of the

St. Louis

. Captain Schroeder penned a personal note to Troper, thanking him for “organizing so efficiently the distribution of my passengers.” That evening, as scheduled, the

St. Louis

began another transatlantic voyage, destination New York City. Making her way up the estuary toward open water, she overtook the

Rhakotis

where the smaller ship lay at anchor. The refugees lined the rails as their former floating home passed slowly by, watching, in the words of one of them, “with one dry eye and one wet eye.” For their part, the crew of the

St. Louis

called out encouragingly, “Good luck to the Jews!”

Nearly all of the 231 crew members had signed on for the return voyage to New York. One who hadn't was the second-class steward Otto Schiendick, who left the ship in Antwerp carrying his hollowed-out walking stick, eager to be reunited with his

Abwehr

contacts in Hamburg.

Captain Schroeder's letter of appreciation to Morris Troper, dated June 18, 1939

.

(Courtesy of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum)

Alex and Helmut, the six members of the Karliner family, and their 216 fellow passengers on the

Rhakotis

steamed back into Antwerp harbor the following morning and were served a hearty breakfast. There was some largely good-natured grumbling about the close proximity of the bunks and dining tables, with one refugee noting sardonically, “We practically had breakfast in bed.” But the food received rave reviews, as it included the first fresh eggs the passengers had enjoyed for weeks.

At two o'clock that afternoon, Morris Troper returned for a final farewell to the refugees, who applauded and whistled wildly as he drove away from the dock to return to his office in Paris. An hour later, the

Rhakotis

weighed anchor and began its journey, first to

Boulogne-sur-Mer and then on to Southampton. A heavy rain began to fall, dampening the spirits of the passengers, who surely must have felt that they'd been sufficiently tempest-tossed for one voyage. One of them confided to his diary, “I fear it is still possible for a cable to recall us to Germany.”

The odyssey of the unhappy people who had boarded the

St. Louis

in Hamburg, those unwanted former citizens of Germany and Austria who had desired so desperately to gain security in the New World, only to find themselvesâmost of themâforced back to the uncertainties of the Old World, was nearly over. But the controversy surrounding their voyage has continued, unresolved, to the present day.

The debate was originally joined in the American Jewish press. On June 13, as the

St. Louis

was steaming back toward Europe but before the deal brokered by Troper had been announced, Samuel Margoshes published an editorial in a newspaper known in Yiddish as

Der Tog

, but which called itself the

National Jewish Daily

. Margoshes headlined his editorial “The Doom of the 907,” and harshly blamed the Joint Distribution Committee and other Jewish organizations for the failure of the

St. Louis

to find a welcome port in the United States.

The editorial began by quoting a frantic cablegram sent by the passengers' committee: “It reads: âWe are floating to our death. Where is your promise to save us?' In my ears these words sound not so much as an appeal but rather as a terrible indictment of our entire Jewish leadership in America.”

Margoshes then leveled his own indictment against the Joint, referring to the “horse-trading” of Lawrence Berenson: “Admittedly, the Joint Distribution Committee was in no easy financial position. On the other hand, can there be any doubt that had the Joint ransomed the prisoners on the St. Louis, that there would have been such an outpouring of gratitude and generosity on the part of American Jewry as to more than offset the sacrifice made by the JDC? Had the Joint rushed to the rescue, instead of counting its pennies and then haggling about the price of 907 Jewish lives, it would have today been the master not only of the heart but also of the pocket of American Jewry. Alas, it was not to be. âCuba was lost for us by haggling,' a committee of the refugees wired

me the other day. It is not the first time in Jewish history that counting costs lost a Jewish battle.”

In his conclusion, Margoshes denounced the lack of effort he perceived among the leading Jewish organizationsâincluding the General Jewish Council, the American Jewish Committee, the B'Nai B'rith, and the American Jewish Congressâon behalf of the

St. Louis

refugees: “It is a bitter thing to say, and I say it not without pain, but the fact remains that as far as preventing or alleviating the tragedy of the 907, Jewish leadership in America might have just as well never existed or been away on a long vacation. Whatever

was

done for the rescue of the Jewish refugees was done in the dark and was shrouded in mystery. No wonder it failed. Its failure spells not only the doom of the 907 but also the bankruptcy of Jewish leadership in America.”

Three days later, with Troper's deal now public knowledge, the

Jewish Daily Forward

fired back with a front-page editorial of its own:

Jews throughout the world have lived in a nightmare during the last two weeks, with the sufferings of the unfortunate refugees aboard the

SS St. Louis

constantly in mind. We lived with these refugees all the time that the boat was floating in American waters. When the refugees left the shores of Cuba to go back to Europe, our deepest sympathy went with them. And together with them, the JDC [the Joint], our most important Jewish relief organization, turned its entire attention to Europe, in order to rescue the refugees. “Five days and five nights,” as it was stated in the cable from Paris, “the European Director of the JDC, Morris C. Troper, was chained to his desk. He appealed to all democratic governments in Europe, and made every possible effort to rescue the refugees.” At last the JDC succeeded in rescuing the unfortunate victims of Hitlerism. For that we must be grateful. The rescue work of the JDC is an important chapter in Jewish history. The JDC spared no effort, ignoring the attacks that some Jewish newspapers directed against it. Evidently the JDC was bent upon rescuing the refugees and had no time to enter into discussions with irresponsible newspapers and writers.

The

Forward

then called out

The National Jewish Daily

, the

Jewish Morning Journal

, and the

Freiheit

for what it called “shameless attacks” upon the Joint “at a time when the most complicated and delicate negotiations about the refugees were going on!” The editorial concluded, “The important work of the JDC deserves our gratitude and it deserves also a better and more sympathetic attitude on the part of the press.”

But the debate about who was to blame for the fate of the

St. Louis

passengers extended beyond dueling Jewish periodicals. The failure of the United States to respond adequately to the crisis had serious implications for the moral standing of the U.S. as a civilized country in an increasingly dangerous world. One of the first to indict the United States for failing an ethical test in the choppy waves off the coast of Florida was a spokesman for another religious perspective. Bishop James Cannon Jr. of the Southern Methodist Church wrote a long letter to the editor of the

Richmond Times-Dispatch

headlined “Shame of the St. Louis.” It read, in part:

During the days when this horrible tragedy was being enacted right at our doors, our Government at Washington made no effort to relieve the desperate situation of these people, but on the contrary gave orders that they be kept out of the country. Why did not the President, secretary of state, secretary of the treasury, secretary of labor and other officials confer together and arrange for the landing of these refugees who had been caught in this maelstrom of distress and agony through no fault of their own? Why did not our Congress take action in accordance with the free and humane spirit which has characterized our people and our Government in the past?

The failure to take any steps whatever to assist these distressed, persecuted Jews in their hour of extremity was one of the most disgraceful things which has happened to American history, and leaves a stain and brand of shame upon the record of our nation. The fact that the Dutch, the Belgians, the French and the British are reported to have arranged to admit these trapped refugees simply adds to the shame upon our own

Government that we have known and seen their misery and have played the part of the priest and of the Levite rather than of the Good Samaritan, and that we have passed by on the other side and left these Jews to whatever fate might befall them on their return to Europe.