All Change: Cazalet Chronicles

Read All Change: Cazalet Chronicles Online

Authors: Elizabeth Jane Howard

Tags: #Sagas, #General, #Fiction

To Hilary and Gerald

CONTENTS

PART THREE July–September 1956

PART FOUR December 1956–January 1957

PART SEVEN November–December 1957

PART EIGHT January–February 1958

PART TEN November–December 1958

THE CAZALET CHRONICLES:

ALL CHANGE

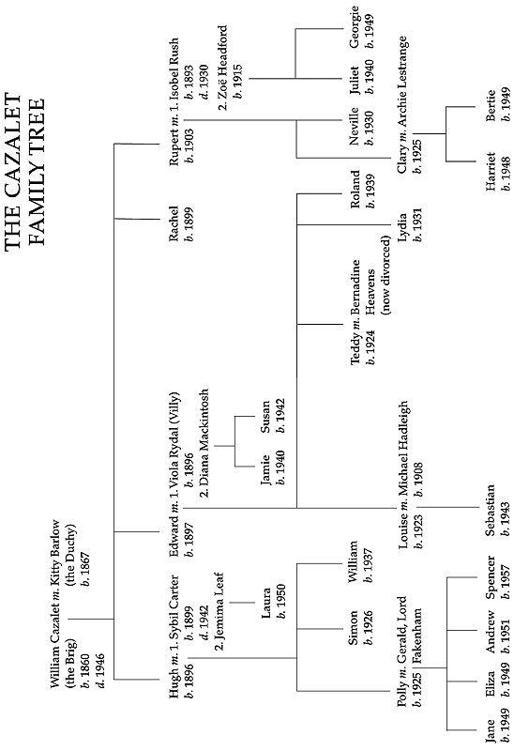

Character List

W

ILLIAM

C

AZALET

, known as the Brig (now deceased)

Kitty Barlow

, known as the Duchy (his wife)

H

UGH

C

AZALET

, eldest son

Jemima Leaf

(second wife)

Laura

Sybil Carter

(first wife; died in 1942)

Polly (married Gerald, Lord Fakenham; their children: Jane, Eliza, Andrew, Spencer)

Simon

William, known as Wills

E

DWARD

C

AZALET

, second son

Diana Mackintosh

(second wife)

Jamie

Susan

Viola Rydal

, known as Villy (first wife)

Louise (married Michael Hadleigh, now divorced; their son: Sebastian)

Teddy (married Bernadine Heavens, now divorced)

Lydia

Roland, known as Roly

R

UPERT

C

AZALET

, third son

Zoë Headford

(second wife)

Juliet

Georgie

Isobel Rush

(first wife; died having Neville)

Clarissa, known as Clary, (married Archie Lestrange; their children: Harriet and Bertie)

Neville

R

ACHEL

C

AZALET

, only daughter

Margot Sidney

, known as Sid (her partner)

J

ESSICA

C

ASTLE

(Villy’s sister)

Raymond

(her husband)

Angela

Christopher

Nora

Judy

Mrs Cripps (cook)

Ellen (nurse)

Eileen (maid)

Tonbridge (chauffeur)

McAlpine (gardener)

Miss Milliment (Louise and Lydia’s old governess, now Villy’s companion)

FOREWORD

The following background is intended for those readers who are unfamiliar with the Cazalet Chronicles, a series of novels whose first four volumes are

The Light Years

,

Marking Time

,

Confusion

and

Casting Off.

Since the summer of 1945 William and Kitty Cazalet, known to their family as the Brig and the Duchy, have lived quietly in the family house, Home Place, in Sussex. The Brig died in 1946, of bronchial pneumonia, but the Duchy lives there still. She is not alone: she and her husband had four children – an unmarried daughter, Rachel, and three sons. Hugh is a widower, but is no longer mourning his first wife, Sybil, with whom he had three children, Polly, Simon and Wills; he has recently married Jemima Leaf, who had been working at Cazalets’, the family timber company. Edward has separated from Villy, his wife, and is contemplating marriage to his mistress, Diana, with whom he has two children. Rupert, missing in France during the Second World War, has returned to his wife, Zoë, Clary and Neville, the children of his first marriage, and Juliet, the daughter who was born to him and Zoë in 1940, after his disappearance. The couple have succeeded in rebuilding their marriage after a difficult start.

Edward has bought a house for Villy. She lives there, unhappily, with Roland, her younger son. She has also taken in the old family governess, Miss Milliment. Villy’s sister, Jessica, and her husband have come into money, an inheritance from an aged aunt. Their son, Christopher, a pacifist and vegetarian, has become a monk.

Edward’s daughter, Louise, hoped to become an actress, but married at nineteen. She has left her husband, the portrait painter Michael Hadleigh, abandoning also her small son, Sebastian. Her brother, Teddy, married an American woman while he was training with the RAF in Arizona. He brought Bernadine home to England, but she was unable to settle and left him to return to America.

Polly and Clary have been living together in London. Polly has been working for an interior decorator and Clary for a literary agent. Through her work, Polly has met Gerald Lisle, Earl of Fakenham, and visited his ancestral home, which needs restoration. Shortage of money had prevented work starting, but Polly has recognised a large number of paintings in the house by J. M. W. Turner, some of which may fund it. She and Gerald are now married.

Clary has had an unhappy love affair with the literary agent but has always been drawn towards writing. Encouraged by Archie Lestrange, a long-standing friend of her father, she has completed her first novel. Throughout her girlhood, Archie had an avuncular relationship with Clary, but they have grown closer, so much so that they have fallen in love and it seems they will marry.

Rachel lives for others, which her friend, now lover, Margot Sidney, known as Sid, a violin teacher, finds difficult. So difficult, in fact, that she had an affair with another woman. When Rachel discovered the truth, a period of estrangement followed but they are now happily reconciled.

All Change

begins nine years later, in 1956.

PART ONE

JUNE 1956

RACHEL

‘Not long now.’

‘Duchy, darling!’

‘I feel quite peaceful.’ The Duchy shut her eyes for a moment: talking – as did everything else – tired her. She paused and then said, ‘After all, I

have

exceeded the time allotted to us by Mr Housman. By twenty years! “Loveliest of trees” – I could never agree with him about that.’ She looked up at her daughter’s anguished face – so pale with smudges of violet under her eyes from not sleeping, her mouth pinched with the effort of not weeping – and, with enormous difficulty, the Duchy lifted her hand from the sheet. ‘Now, Rachel, my dear, you must not be so distressed. It upsets me.’

Rachel took the trembling, bony hand and cupped it in both of hers. No, she must not upset her: it would indeed be selfish to do that. Her mother’s hand, mottled with liver spots, was so wasted that the gold band of her wristwatch hung loosely, the dial out of sight; her wedding ring was tilted to halfway over her knuckle. ‘What tree would you choose?’

‘A good question. Let me see.’

She watched her mother’s face, animated by the luxury of choice – a serious matter . . .

‘Mimosa,’ the Duchy said suddenly. ‘That heavenly scent! Never been able to grow it.’ She moved her hand and began fretfully fumbling with her bedclothes. ‘No one left now to call me Kitty. You cannot imagine—’ She seemed to choke suddenly, trying to cough.

‘I’ll get you some water, darling.’ But the carafe was empty. Rachel found a bottle of Malvern water in the bathroom, but when she returned with it, her mother was dead.

The Duchy had not moved from her position, propped up by the square pillows she had always favoured; one hand lay on the sheet, the other clasping the plait of her hair that Rachel did for her every morning. Her eyes were open, but the direct, engaging sincerity that had always been there was gone. She stared, sightless, at nothing.

Shocked, mindless, Rachel took the raised hand and placed it carefully beside the other. With one finger she gently closed her mother’s eyes, and bent down to kiss the cool white forehead, then stood transfixed as she was assailed by streams of unconnected thoughts – it was as though a trapdoor had suddenly opened. Childhood memories. ‘There is no such thing as a white lie, Rachel. A lie is a lie and you are never to tell them.’ When Edward had spat at her standing in his cot: ‘I don’t listen to people who tell tales.’ But her brother was reprimanded and never did it again. The serenity that rarely seemed disturbed – only once, after seeing Hugh and Edward off to France, aged eighteen and seventeen respectively, calm, smiling, while the train slowly left Victoria station. Then she had turned away, and had pulled out the tiny lace handkerchief that was always tucked into her wristwatch. ‘They are only boys!’ There was a small but distinct strawberry mark on the inside of that wrist, and Rachel remembered wondering if she kept the handkerchief there to conceal it, and how she could have had such a frivolous thought. But the Duchy did cry: she cried with laughter – at the antics of Rupert who, from his earliest years, had made everyone laugh; at Rupert’s children – notably Neville; at people she regarded as pompous; tears would stream down her face. Then, too, at ruthless Victorian rhymes: ‘Boy gun, joy fun, gun bust, boy dust’, and ‘Papa, Papa, what is that mess that looks like strawberry jam? Hush, hush, my dear, it is Mama, run over by a tram’. And music made her cry. She was a surprisingly good pianist, used to play duets with Myra Hess, and had loved Toscanini and his records of the Beethoven symphonies. Alongside her rule of plain living (you did not put butter

and

marmalade on breakfast toast; meals consisted of roast meat, eaten hot, then cold and finally minced with boiled vegetables, and poached fish once a week, followed by stewed fruit and blancmange, which the Duchy called ‘shape’, or rice pudding), she lived a private life that, apart from music, consisted of gardening, which she adored. She grew large, fragrant violets in a special frame, clove carnations, dark red roses, lavender, everything that smelt sweet, and then fruit of every description: yellow and red raspberries, and tomatoes, nectarines, peaches, grapes, melons, strawberries, huge red dessert gooseberries, currants for making jam, figs, greengages and other plums. The grandchildren loved coming to Home Place for the dishes piled with the Duchy’s fruit.

Her relationship with her husband, the Brig, had always been shrouded in Victorian mystery. When Rachel was a child, she had seen her parents simply in relation to herself – her mother, her father. But living at home with them all of her life, and while continuing to love them unconditionally, she had nevertheless grown to perceive them as two very different people. Indeed, they were utterly unalike. The Brig was gregarious to the point of eccentricity – he would bring anyone he met in his club or on the train back to either of his houses for dinner and sometimes the weekend, without the slightest warning, presenting them rather as a fisherman or hunter might display the most recent salmon or stag or wild goose. Whereupon – with only the mildest rebuke – the Duchy would tranquilly serve them with boiled mutton and blancmange.