All The Devils Are Here: Unmasking the Men Who Bankrupted the World (71 page)

Read All The Devils Are Here: Unmasking the Men Who Bankrupted the World Online

Authors: Joe Nocera,Bethany McLean

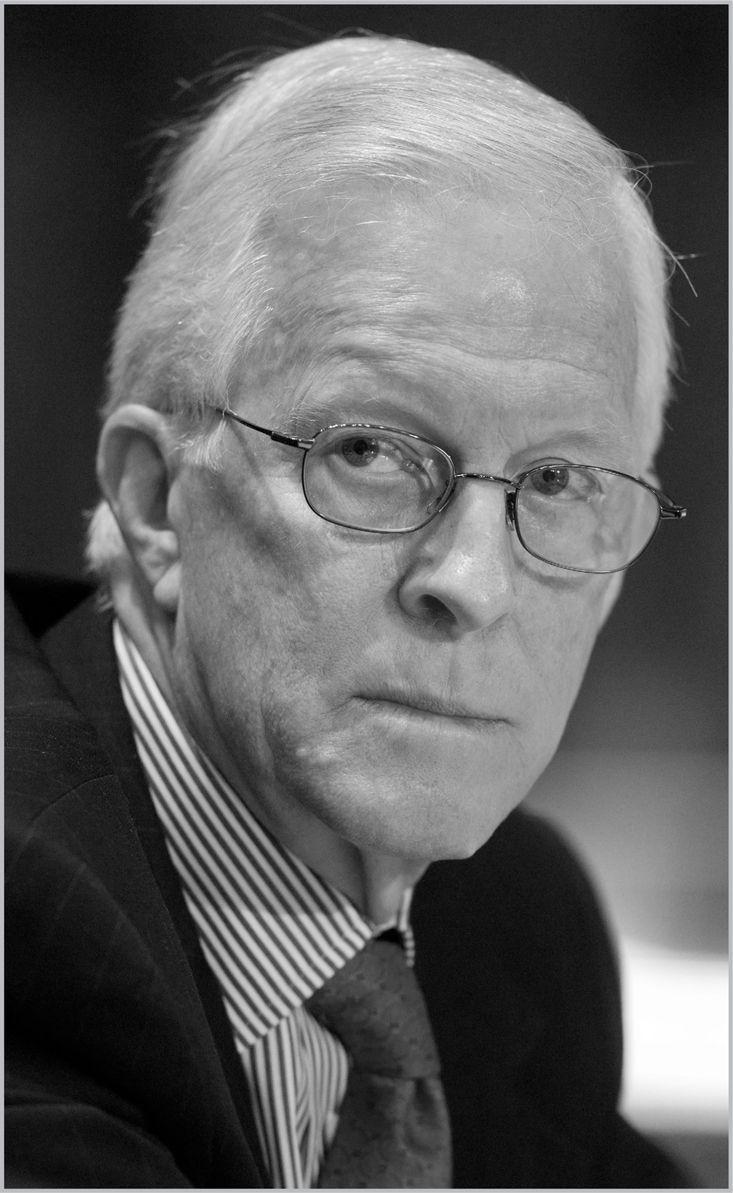

Martin Sullivan spent his entire career at AIG, taking over as CEO after Greenberg’s departure. Although he pulled AIG out of one crisis, he seemed increasingly lost as the financial crisis closed in on the company.

(© Ramin Talaie/Corbis)

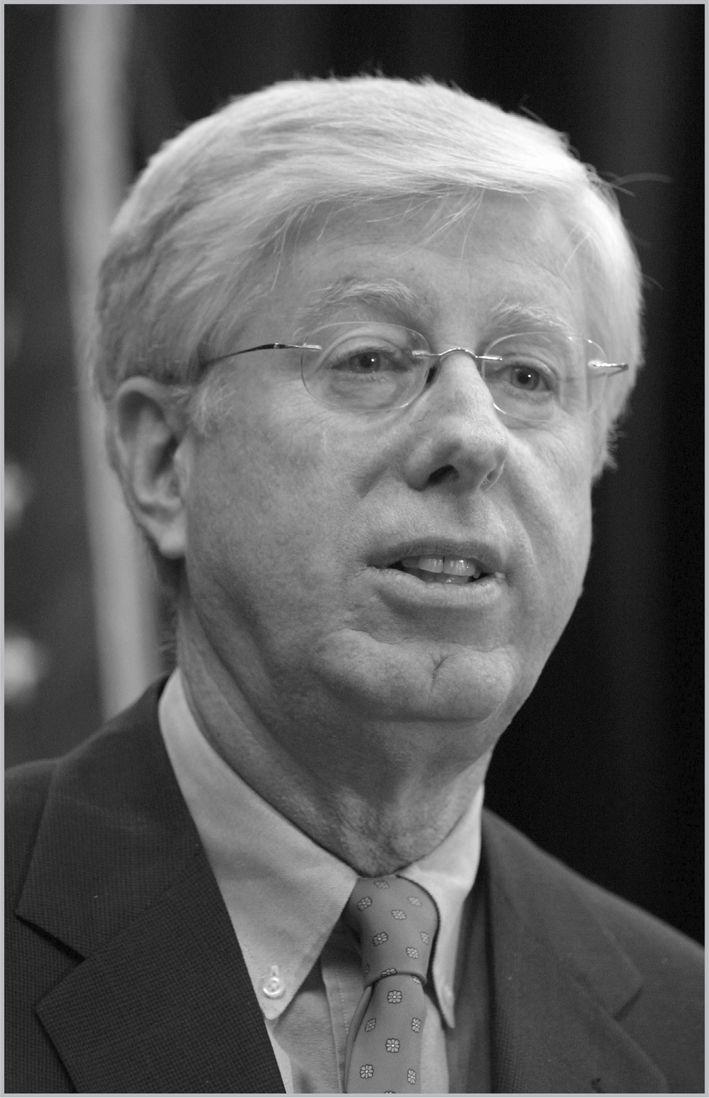

Robert Willumstad stepped in as the CEO of AIG in the summer of 2008 after Sullivan’s dismissal. He planned to unveil his strategic plan in September. But by then the government had been forced to rescue the company.

(© Bloomberg/Getty Images)

Stan O’Neal, the CEO of Merrill Lynch, ignored the risks of the subprime mortgage-backed securities that were building up on Merrill’s balance sheet until it was far too late. When he tried to salvage the situation by selling Merrill Lynch to a big bank, the board fired him instead.

(© Chip East/Reuters)

Jeff Kronthal was a veteran trader at Merrill Lynch. For years, he limited the company’s exposure to CDOs backed by subprime mortgages. In 2006 he and his team were summarily fired—and their replacements loaded up on subprime securities.

(© Dan Kronthal)

State attorneys general like Iowa’s Tom Miller fought to defend borrowers from the abuses of subprime lenders like Ameriquest.

(© Bloomberg/Getty Images)

Andrew Forster, one of Joe Cassano’s deputies at AIG-FP, grappled with the company’s exposure to subprime default risk.

(© Bloomberg/Getty Images)

As Treasury secretary, Hank Paulson claimed the government seizure of Fannie and Freddie was the single thing he had done during the crisis of which he was most proud.

(© Win McNamee/Getty Images)

O

n July 21, 2010, President Obama signed into law the Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act, a 2,300-page, 383,000-word piece of legislation that marked, unquestionably, the biggest change in the regulation of the financial industry since the aftermath of the Great Depression. The law had been two years in the making, and most of it, in one way or another, was a reaction to the excesses that had led to the financial crisis.

The Federal Reserve would get new powers to look broadly across the financial system. A council of federal regulators led by the Treasury secretary would help ferret out systemic risk. A new consumer agency was created to help end the lending abuses and keep people from getting loans they could never hope to pay back. Under this new law, most derivatives will supposedly be traded on an exchange—meaning in the clear light of day, where prices and profits are transparent. The bill creates a process to liquidate failing companies, so that there is a reasonable alternative to bailouts. It outlaws proprietary trading at financial institutions that accept insured deposits—the so-called Volcker Rule. “Because of this law, the American people will never again be asked to foot the bill for Wall Street’s mistakes,” President Obama said. Well, maybe.

Footing the bill for Wall Street’s mistakes was precisely what the American taxpayer had been doing since September of 2008, in a hundred different ways. And Americans were angry about it. It wasn’t just the obvious examples—like the $182 billion in federal help that AIG required before it was over. The Federal Reserve guaranteed money market funds. It bought tens of billions of dollars of “toxic assets”—that was the culture’s shorthand for securitized subprime mortgages after the crisis—to help the banks get back on their feet. The FDIC, meanwhile, guaranteed all new debt issued

by bank holding companies, without which they could not have funded themselves in the debt markets. Let’s face it: they were all now government-sponsored enterprises. And so they would remain, despite protestations to the contrary. Because as everyone learned with Fannie and Freddie, implicit government guarantees, whether they arise from a congressional charter or from the market’s belief that the government will stand behind a failing company, are awfully hard to take away.

It took a while after Lehman weekend for the panic to quell. It is easy to forget now, but Morgan Stanley and Goldman Sachs both found themselves caught in the contagion, and could well have gone under. Morgan was saved only when it managed, at the last moment, to make a deal with Mitsubishi UFJ, a big Japanese bank. Goldman, along with Morgan Stanley, was allowed to become a bank holding company, thus receiving a government imprimatur that Dick Fuld could never get for Lehman Brothers. Washington Mutual was sold in a fire sale to J.P. Morgan. Wachovia was on the verge of collapse when Wells Fargo bought it in December 2008. Citigroup needed multiple infusions of federal cash.

So long as there was that deep uncertainty of how big the black hole was—that paralyzing fear that nobody knew anymore what anything was worth—the crisis didn’t abate. “The way I think about the crisis is that it occurred because of the systemic abuse of trust in capital markets,” says Australian financial analyst and historian John Hempton. “The blowups of subprime, then of Bear Stearns, and then of Fannie exposed massive lies. Then we went from a collective belief in soundness to a collective belief in insolvency.”

It took the absolute certainty that the United States government would use its financial might to prevent that insolvency to stanch the bleeding. That was Paulson’s most famous act during the crisis: along with Bernanke, he pleaded with Congress to give Treasury $700 billion that he could use to shore up the system. The money was called the Troubled Asset Relief Program, or TARP. On October 13, his $700 billion in hand, Paulson met the CEOs of the eight biggest banks in a Treasury conference room. He told them that they would all be taking money from the government, like it or not. Although several came to regret taking it, none had the nerve to say no to Hank Paulson.

The passage of the TARP marked the first outpouring of populist fury. Despite all the apocalyptic talk that the financial system was at stake, you

had to feel that in your gut to believe it, because the only way anyone could prove it would have been to not pass the bill and see if the financial system went under. It was hard to make the connection between a big bank in New York that traded credit derivatives and a family in Ohio that couldn’t get a loan if that faraway bank went under. All people could really know for sure was that taxpayers’ money was going to prop up the very firms whose greed and mistakes helped cause the crisis.

The anger didn’t subside after the danger had passed. If anything, it grew stronger. It would build in waves, crest, and then take aim at a different target.

People raged at the Bank of America–Merrill Lynch deal—at the way John Thain had accelerated the payment of $3.6 billion in bonuses to Merrill traders days before the deal was completed; at the way Ken Lewis had averted his eyes; at the way Bernanke and Paulson had pushed and prodded and bludgeoned Lewis into completing the deal when the CEO got cold feet at the last minute. The deal almost certainly averted Merrill’s bankruptcy. It didn’t matter; people wanted blood. Congress held three hearings on the Bank of America–Merrill Lynch deal, mainly so that members of Congress could vent on behalf of their constituents.