All the Way (13 page)

Authors: Jordin Tootoo

The other teams had some future stars, tooâincluding a seventeen-year-old playing for Russia who no one had ever heard of before named Alexander Ovechkin.

But frick, we were just kids back then. The shit that we did. . . . We were horny young men. We were in Halifax and we had every goddamned girl hitting on us. What are you going to do?

Let's start slaying these broads.

And it wasn't just one-onone action. A few of the guys would get a couple of girls after practice and head into one of the rooms. Enough said.

At the beginning of the tournament I don't think any of us really realized what was at stake, and how much pressure there was on us to win. I didn't really understand that until after the gold-medal game. We went undefeated through the preliminary round and then beat the Americans 3â2 in the semifinals.

The Russians were undefeated as well when we met them in the finals. Of course, Canada versus Russia has been the big hockey rivalry going all the way back to 1972. It felt like the whole country was watching us.

It was nuts in the arena. When we scored a goal, I thought my eardrums were going to explode. We were up 2â1 going into the third period. The boys were pretty relaxed. But thenâ

boom, boom

âthe Russians scored two goals and it was all over. We lost 3â2.

I was on the ice for the last shift of the game. I'll never forget looking over at my best friend, Scottie Upshall, right after the game ended. He was the captain of that team. He'd scored the second goal of the game. I'd known him since Spruce Grove, when we'd played on a select team together. We have been buddies ever since. The game was over, we'd lost, and Scottie was bawling his eyes out.

Holy fuck.

That's when I realized that we'd let this game slip away in our home country. I had never seen Scottie like that, before or since. It's heartbreaking, as a teenage kid, to let your country down. You're playing in the biggest tournament of your life. All of that raw emotion from the fans is just pouring down on you and then that buzzer goes off and you realize that you've failedânot only failed your teammates, but failed your country.

Everyone remembers how the Russians celebratedâon

our

turf. I was standing on the ice, watching them, and then looking at the other guys on our team. No one had to say it. We were thinking,

Fuck these guys. Let's fucking beat them up right now.

I

know that was my instinct.

Look at this fucking donkey riding his stick down the ice. Fuck him.

But I had to keep it together because if I did something stupid, that would be it for me ever representing Canada again.

If that had happened in a normal junior game, that guy riding his stick would have wound up in the hospital.

My popularity blew up after that tournament. I only scored one goal and one assist, but all the reporters said that I was the fans' favourite Canadian player because of the style of hockey I played, because I would hit anything that moved. Things just skyrocketed from there and carried over into the rest of the season with the Wheat Kings. Suddenly my name was all over the place. I was crushing guys left and right, playing good old Canadian hockey, and the people in the arena and watching on television loved it. It felt like it happened overnight. The nation of Canada took me under its wing and I rode that wave for the whole two weeks of the tournament. Everywhere I went, people were praising me. I said, “Okay, relax, I'm just a regular guy like anyone else.”

That was by far the highlight of my career thus far: being part of Team Canada and that whole experience. No one can ever take that away from me. I can tell my kids one day that I represented this great country. We didn't win the gold medal but that didn't change the way people felt about me. That tournament really put my name on the map, and Tootoo became a household name in a lot of places.

WHEN I RETURNED to Brandon after the tournament, it felt like everything had changed. In every arena I played in after the World Juniors, every barn in The Dub, people were applauding me, even when I was on the visiting team. Fans would stand around waiting for me after games. Oh my God, it was unbelievable. I was getting gifts from other teams, congratulating me, when the Wheat Kings would go to their rink to play them. It was amazing.

But the best reaction came from other First Nations people. I remember going to play in Prince Albert, Saskatchewan, and three-quarters of their fans were Aboriginal people from the reserves around there. They gave me a gift from the reserve; it was one of their traditional blankets with some special designs on it, plus some sweetgrass. When I scored a goal the place erupted, even though I was playing for the Wheat Kings. After the game there were so many fans waiting around our bus that we needed extra security. I was fucking loving it.

I'm very thankful to have a following like that among Aboriginal people. I can't really express those feelings in words. The way I like to say thank-you to them is to actually visit them and make time to sign autographs until the last person has got his autograph or picture. I don't want people to be shy to come up to me. This profession doesn't last forever and those kinds of things don't last forever. I want to enjoy it while it's happening and thank the Aboriginal people for letting me be a role model to them. Little do they know that they're what inspires me. I want to be a better professional for them, both on and off the ice.

I'm an Inuk, but I identify strongly with all First Nations

people. I think there are a lot of similarities among us, no matter what part of the country we come from. We are very loyal to our traditions, our culture, and our people. We're small townâoriented individuals who have a simple life and enjoy it, rather than having all of these materialistic things. We draw a lot from our roots. When I go to these Aboriginal communities and reserves, those are the similarities I see to the place where I grew up.

I'm not really a political person but I do believe that First Nations people run as one, and we just want to be treated equally. It doesn't matter what colour skin you have or where you come from. We're all human beings and we want to be treated the way everyone should be treatedâand that's fairly and equally, and not being judged.

IT WASN'T JUST the hockey fans in Canada who noticed me during the World Juniors tournament. I also grabbed the attention of David Poile, the general manager in Nashville, and the Predators coaching staff. They already liked me enough to have drafted me and they had liked what they saw of me in training camp. But I think that when they saw me in the tournament, it gave them an entirely different sense of my potential, of what kind of player I could be in the NHL. I won't say it was a no-brainer for the Preds to give me every opportunity to make the team the following year just because of that tournament, but they definitely saw something there and that carried over to camp the next fall.

I finished the season in Brandon with 74 points in 51 gamesâtied for the team lead even though I missed a bunch of time because of the World Juniors. I also had 216 penalty minutes, which was a lot, but there were guys in the league with way more than that. I was learning to control when I fought and when I didn't fight, to make better decisions, which made me a more valuable player. If you look at my statistics, I was a plus-13 that year. That tells you how much I was contributing.

I was a leader on that team. I'm not the most vocal guy, but I try to lead by example. Being a leader means that, when times are tough, your teammates need to be able to lean on you and be open to talking about issues. This applies not just in the hockey world but away from hockey as well. Not every player has the balls to go up to the coach and talk about certain situations. That's what your leaders are for. I admit I wasn't the greatest at the vocal part. Other guys like Ryan Craig and Brett Thurston played that role. But my teammates always knew where to find me when we were on the ice and things got tough.

We won our division, but were beaten by Red Deer in the third round of the playoffs. Those were great teams in Brandon, but it always seemed like we couldn't get past Red Deer. We were up 3â1 in that series. That's when I broke my first ribâright underneath my collarbone. It was just a freak accident. In game five I kind of swiped at a guy behind our net and it just popped. After the game, we were jumping on the bus to head back to Red Deer and I was in fricking pain. I could barely breathe. But I ended up fighting through it and playing through it. I wasn't 100 percent but I didn't want to let my teammates down, so I

didn't say anything about it to anyone. It was a battle. But that's what makes the playoffs fun. I went to the doctors after the series and they said, “Gee, you were pretty lucky. If that bone had actually cracked, it probably would have cut one of your main arteries and you would have been done in two minutesâand you wouldn't even have known what hit you.” It was a surreal moment, hearing that. Thank God that didn't happen.

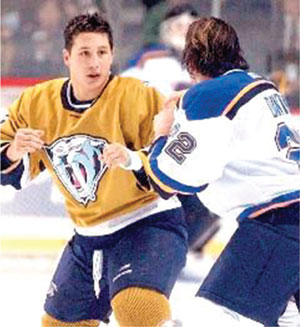

I may be the first Inuk to make it to the NHL, but my people have been making a living on the ice for a long time. Above is my father beside a muskox he brought down. Below is my first regular-season fight in the NHL, against Mike Danton. Life on the ice can be dangerous and you have to respect that. But you never show fear.

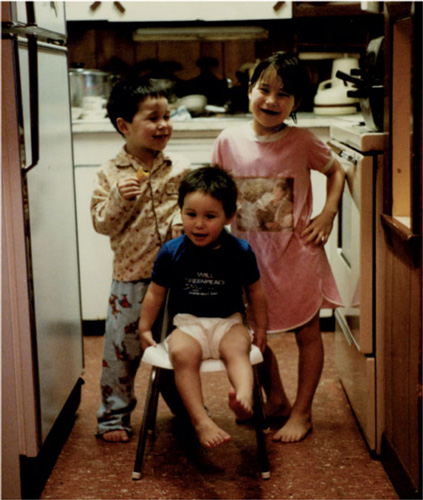

My family has always meant the world to me. The people around you are the people who shape who you are. Above are my parents at their wedding. To the right are the three of us kids in the kitchen in Rankin. That's Terence on the left and Corrine on the right. I'm the little guy in the middle. And below, that's the three of us, all grown up, at Corrine's wedding.