Altar of Eden (5 page)

Authors: James Rollins

Lorna hated to close the door on Igor’s plaintive plea, but she had a bigger mystery to solve. Still, a pang of sympathy coursed through her, dulling the sharp edge of her professional interest.

As the isolation door clicked shut, her boss was already halfway down the hall, moving with long, purposeful strides. He had been speaking, but she caught only the last bit.

“ . . . and we’ve already started PCR tests to begin amplifying the key chromosomes. But, of course, DNA sequencing will take most of the night.”

She hurried to close the distance with Carlton—both physically and mentally. Together they headed down another hallway and reached the double doors to the suite of genetic labs that occupied this wing of the ACRES facility.

The main lab was long and narrow, lined on both sides by bio-hazard hoods and workstations. The latest genetic equipment filled shelves and tables: centrifuges, microscopes, incubators, electrophoresis equipment, a digital camera system for visualizing DNA, and racks of pipettes, glassware, scales, vials of enzymes and PCR chemicals.

Carlton led the way to where two researchers—a man and a woman—were crouched before a computer monitor. The pair stood so close together, both wearing white lab coats. They reminded Lorna of the conjoined monkeys, bonded at the hip just like Huey and Dewey.

“This is amazing,” Dr. Paul Trent announced and glanced over a shoulder as she reached them. He was young, thinly built, with wavy blond hair combed behind his ears, looking more like a California surfer than a leading neurobiologist.

Paul’s wife, Zoë, stood next to him. She was Hispanic. Her black hair was bobbed short—shorter than her husband’s—framing wide cheekbones, lightly freckled. Her lab coat did little to hide the generously curved body beneath.

The two were biologists from Stanford, wunderkinds in the field, earning their degrees before their mid-twenties and already well regarded professionally. They were in New Orleans on a two-year grant researching neural development in cloned animals, studying the structural differences between the brains of cloned specimens and their original subjects.

The pair of doctors certainly had come to the right place.

ACRES was one of the nation’s leading facilities involved with cloning. In 2003, they had been the first to clone a wild carnivore, an African cat named Ditteaux, pronounced

Ditto

for obvious reasons. And in the coming year, the facility was about to begin the commercial cloning of pets as a method to raise funds for their work with endangered species.

Zoë stepped back from the computer monitor. “Lorna, you have to see this.”

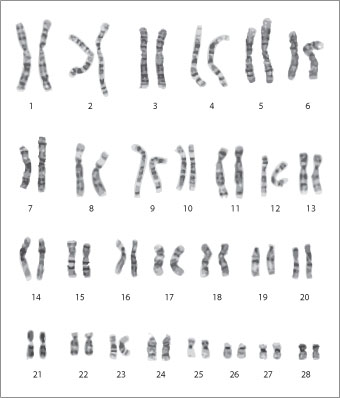

Lorna moved closer and recognized a karyogram on the screen. It showed a set of numbered chromosomes lined up into a chart.

Karyograms were built by using a chemical to trap cell division in its metaphase stage. The chromosomes were then separated, dyed, and sequenced via digital imaging into a numbered karyogram. Humans carried forty-six chromosomes, divided into twenty-three pairs. The monitor showed twenty-eight pairs.

Definitely not human.

Carlton explained, “We built this karyogram from a white blood cell from one of the capuchin monkeys.”

From the general excitement, Lorna knew there remained another shoe to drop.

Paul spoke up, his voice was full of wonder. “Capuchins normally have a complement of twenty-seven pairs of chromosomes.”

Lorna stared at the karyogram on the screen. “But there’s twenty-

eight

here.”

“Exactly!” Zoë said.

Lorna turned to the facility’s director. “Carlton, you said you still wanted to repeat the test. Surely this is a lab error.”

“It’s under way, but I suspect we’ll confirm the original findings here.” He nodded to the computer.

“Why’s that?”

Carlton leaned forward, grabbed the computer mouse, and toggled through another five genetic maps. “This next karyogram is from the conjoined twin of the first monkey. Again twenty-eight chromosomal pairs. Same as the first. The next studies are from the lamb, the jaguar cub, the parrot, and this last is from the Burmese python.”

The python?

Frowning, she glanced across the lab to where an incubator housed the clutch of snake eggs. In his desire to confirm what she was beginning to suspect, Carlton must have opened one of the eggs to get at the developing embryo inside and obtain its DNA sample.

“Pythons typically have thirty-six pairs of chromosomes,” Carlton continued. “A mix of micro- and macro-chromosomes.”

Lorna read off the screen. “There are thirty-seven here.”

“That’s right. One pair more than normal. Like all the rest. That’s why I’m sure we’ll get the same results when we run the genetic studies again. It’s beyond statistical probability that the lab came up with the same error six times in a row.”

Lorna’s mind reeled as she struggled to come to grips with what this implied. “Are you saying that each of the animals from the trawler is showing the same genetic defect? That each is carrying an extra set of chromosomes?”

Such genetic abnormalities occasionally occurred in humans. A single extra chromosome caused a child to be born with Down syndrome. Or there was Klinefelter’s syndrome, where a male was born with two X chromosomes, forming an XXY karyotype. And in rare instances, some people were born with an extra

pair

of chromosomes. Abnormalities this severe usually resulted in early death or severe mental retardation.

She frowned at the screen. None of her animals exhibited such debilitation. The confusion must have been plain on her face.

“I don’t think you’re understanding the full thrust of what we’re saying,” Carlton said. “This extra pair of chromosomes isn’t the result of a genetic error. It didn’t come about from a random mistake in cell division in a sperm or egg.”

“How can you be so sure?”

Carlton manipulated the mouse and flipped through the six karyograms again. He pointed to the last chromosome pair on each of the studies.

“The specimens from the trawler aren’t just carrying an extra set of chromosomes,” the director continued. “They’re carrying the

same

ones.”

Only now did Lorna recognize that the

extra

pair of chromosomes in each of the species looked identical. As the implication sank in, understanding began to slowly well up. It felt like a tide shifting the foundation under her.

Impossible.

Carlton poked at the computer screen. “That is not an error of nature. That’s the hand of man. Someone put that extra pair of chromosomes in all these animals.”

“Who . . . ?” Lorna mumbled out, unbalanced to the point of feeling dizzy, but also oddly excited by it all.

Carlton turned to her, his bushy gray eyebrows resting high on his forehead. His wide eyes shone with raw curiosity. “The bigger question, my dear, is

why.”

Deep in the bayou, Danny Hemple’s father waded through the reeds. “You’re trying my last nerve, boy. Sometimes you’re as useless as tits on a bull.”

Danny didn’t argue. He knew better. At seventeen, he was nearly as big as his father, but not even half as mean. He’d once watched his dad beat a man bloody with the handle of a hammer, payback for shortchanging him on his share of a fishing haul.

At the moment Danny watched his father drag a crab trap out of the muddy reeds. It didn’t belong to them. And it wasn’t some old barnacle-encrusted trap that had been long abandoned. It looked brand-spanking-new with a fresh line, buoy, and legal tag still attached.

His father used a pocketknife to cut the line and tag away. He slogged through the reeds with his prize. Danny spotted a dozen or so good-size Louisiana blue crabs scuttling within the stolen trap.

“Boy, get your thumb out of your ass and move the damned boat closer. We don’t have all day.”

His father wore waders held up by suspenders as he worked through the shallows. Danny poled the boat closer to him. It was a half-rusted airboat that’d had its fan removed and replaced with an old outboard Evinrude. This close to the muddy bank it was too shallow to use the engine—and it would be too noisy anyway. What they were doing could get them in big trouble with the state wildlife guys.

Storms like the one last night wreaked havoc on the thousands of crab traps staked along the waterways near the Gulf. Surges ripped them from their moorings and cast them deeper into the surrounding swamps.

Like throwing out free money,

his father had often quipped.

Danny had joked with his friends that it was more like casting pearls before swine. He had made the mistake of repeating that joke within earshot of his father. Danny’s nose still had a knot from that old break.

“Come get this already! There’s at least two more.”

Oink, oink,

Danny thought sourly to himself and poled forward.

Once close enough, he took the trap from his father’s arms and added it to the four already stacked in the boat. It was good haul, and as much as he might despise what they were doing, he understood why. At eight dollars a pound for claw meat and twice that for jumbo lump, they might clear close to a grand for the afternoon’s work. Not to mention reselling the crab traps back to the same people who once owned them.

Scavenging like this wasn’t lost on the Fish and Wildlife guys. If the wardens didn’t haul you to jail and fine your ass, they held out an open palm for their cut of the bounty. The price for doing business out here, they explained. But that wasn’t the worst danger. There were other hunters like Danny’s father. Fights broke out over territories, sometimes leading to bloodshed. It was said the alligators out here were well fed.

Aware of that threat, Danny kept a watch on the bayou around him, though mostly with his ears. It was hard to see much farther than twenty yards in any direction. All around, forests of cypress and sweet gum dripped with mosses and vines and shut out the world. Branches laced over the narrow canal.

He listened for the trebling whine of a warden’s airboat or the growl of another scavenger’s outboard engine. So far all he heard was the whine of mosquitoes and the warbling calls of swallow-tailed kites as the birds swept through the branches overhead.

Danny wiped his brow with a handkerchief and stuffed it back in his pocket. The day’s heat seemed trapped under the branches. Even the shade offered little relief. To make things worse, the crab pots had begun to stink.

But what could he do?

With no choice, he poled after his father, keeping along the edges of the reeds. They were deeper into the bayou than they normally searched. And out later than usual. Danny knew why his father was taking such a risk. His little sister’s leukemia had relapsed. With his father between jobs, they had no health insurance. The storm had been a godsend. So Danny didn’t begrudge his father’s gruff manner for once. He recognized the worry and shame that lay behind it.

“I think there’s another trap over there, Pop.”

Danny pointed his pole toward where a small branch of the canal dove into deeper shadows. A single white buoy floated in the current near the entrance.

“Then go get it while I free this one. Line’s all tangled in some roots.”

As his father cursed behind him Danny sank his pole into the water and punted his boat toward the side channel. The narrow waterway was covered in a layer of water lilies and wound itself into a dense tangle of forest. It looked more like a tunnel than a creek.

He had to work the boat into the channel to reach the stray buoy. A loud splash gave him a start. He turned to see a raccoon swimming across the main channel. It paddled quickly away. Danny scowled at it. Normally the vermin were not that frightened of people. And it was a foolhardy flight to begin with. Many a raccoon ended up as a snack for a hidden alligator.

Before he turned away, a second coon leaped from a branch, sailed far out, and splashed into the water. He puzzled at their panic.

“Whatcha lookin’ at!” his father called at him. “Hurry it up already.”

Danny frowned and returned to the task at hand. He leaned down and grabbed the buoy. He hauled it up and drew in the line. He felt the weight of the submerged trap. From experience, he knew it was a good haul. He braced his legs for balance and hauled the trap out of the water. Crabs packed the wire cage. A smile spread over his face as he calculated the value of the catch.

He dragged the trap into the boat and stacked it with the others. As he shifted to pole out of the side channel, a flash of white drew his eyes deeper down the waterway. He pulled a low-hanging branch out of the way. A tangled knot of four buoys floated about fifty feet away.

All right . . .

He used the branch to pull him and the boat deeper down the channel, then poled the rest of the way. Though focused on his goal, he kept a watch for any suspicious logs on the banks or any telltale peek of a scaly snout. Alligators often nested in such secluded channels. He didn’t overly worry. Only during mating season did bull alligators grow aggressive and females attack anything that approached their nests. Besides, like his father, he had a holstered pistol at his hip.

He reached the cluster of buoys and was about to lean over and begin untangling them when he saw that their lines trailed toward shore. He spotted the cages abandoned at the edge of the water. Each was mangled and torn open, as if dropped into a wood chipper. He saw no sign of crabs.

His first thought was that some bull alligator had gone for an easy meal, but a cold finger of dread traced his spine. In all his years, he’d never seen an alligator attack a crab pot. And considering how heavy the traps were, it took something big to drag them to shore.

But if not an alligator . . .

He swallowed hard, his mouth gone dry. He straightened and poled away, retreating down the channel. He remembered the pair of raccoons hightailing it away. Something had spooked them, maybe something more than a kid in a boat. He stared back at the mangled cages, all too conscious of the stinking cargo sharing his boat.

He poled away faster.

A loud

crack

of a branch wheeled him around. His heart jackhammered into his throat. A thick tree branch crashed down and landed across the waterway, cutting off his escape.

Bushes rustled on the opposite shore—as if something had leaped out of the tree and landed on the far side. Danny dropped his pole and snatched for his pistol. He fumbled with the snap securing the weapon.

The rustling retreated, going fast.

Danny never caught sight of it, but he sensed something large and stealthy. Frozen in place, he strained his ears, worrying it might circle back.

A sudden shout almost toppled him out of the boat.

“Boy! Put your dick back in your pants and git back here!”

Only then did Danny realize the direction of the rustling. Where it was headed.

No . . .

ELDON HEMPLE KNEW

something was wrong. He knew it before he heard his son’s terrified scream.

“DAD!”

Eldon had hunted the swamps and bayous since he was knee-high to his own father, and his instincts were honed to a sharp edge. The sudden stillness was the only warning. It felt as if the sky were pressing down, like before a big storm.

He stood ankle-deep in the shallows, buried in a thicket of reeds and palmettos. He lowered the crab trap back in the water and freed his pistol. He turned in a slow circle, staring without blinking. His body screamed for him to run, a primal urge. He fought against it, not knowing the direction of the danger.

He strained to listen—for a splash, for the snap of a branch—some warning. Terror squeezed his chest. Fear not so much for his own life, as for his son’s. He rode the boy hard, but he loved him even harder.

Then he heard it. Behind him. A harsh cough. Not like a man, but more like the chuffing of some beast. A low growl followed.

He swung an arm blindly behind him and fired, popping off a sharp series of blasts. At the same time he ran in the opposite direction, toward the deep water.

“Danny! Get outta here!”

He crashed through the reeds. Razor-edged leaves cut his face and bare arms. If he could get to deep water, dive into the channel . . .

Behind him, something crashed through the palmettos. Only then did he realize the cough and growl had been purposeful, meant to flush him out.

The reeds broke around him. Open water lay ahead. He bunched his legs for a leaping dive—but something massive struck his back, pounding him facedown into the shallow water.

All air was knocked from his lungs. Knives cut into his shoulder and back. He fought to get his arm around, to fire blindly over his shoulder. He managed one squeeze, the gun near his ear. The blast deafened, but not enough to miss the hissing scream that followed, full of blood and fury.

A shadow fell over him, blocking the sun.

He felt hot breath on his neck. Jaws clamped onto the back of his head and shoved his face under the water and into the boggy mud. He felt pressure in his skull, a moment of piercing pain, a crack of bone— then nothing but darkness.

DANNY HEARD THE

gunshots, the piercing scream of rage, the call for him to flee. He knew he had only moments. Bobcats and bears hunted the Louisiana wetlands, but whatever had made that cry was far larger and had no place among its swamps and bayous. The hairs rose all over his body, vibrating to that scream.

He grabbed his pole and propelled his boat away from the main channel. It was the only direction open to him. The fallen tree limb blocked his way. It was far too large and tangled to move on his own. And he knew he had no time to struggle with it. He had to get as far away as possible.

As he poled, he listened for more gunshots, a blistering shout, any sign that his father was still alive. But the bayou had gone quiet. Even the mosquitoes seemed to have grown more hushed.

He dug the pole into the bottom mud and shoved. He passed the spot with the mangled crab pots and continued deeper into the maze of hillocks and dense stands of cypress. He didn’t know this section of the bayou. All he knew was that he had to keep moving.

The weight of the pistol helped keep him breathing. He had shoved the gun into his belt, not trusting he could free it from its leather holster in time.

Just keep moving . . .

It was his only hope. He needed to reach open waters, maybe even the Gulf itself. But he realized he was headed in the wrong direction, north instead of south. He had no hope of reaching the Mississippi, but small settlements lay between here and the Big Muddy. If he could reach one, raise an alarm, stir up men . . .

men with lots of guns

. . .

Time slowly passed, measured by the pounding of his heart. It felt like hours, but was probably less than one. The sun hung low on the horizon. At some point noises returned to the swamp: the croak of frogs, the whistling of birds. He even welcomed the buzzing clouds of mosquitoes. Whatever monster hunted the swamps must have decided not to give chase.

The thin channel opened at last into a small lake. He poled into the center of it, glad to see the shoreline retreat around him. But the sun had dropped below the tree line, turning the lake’s surface into a black mirror.

It was in the reflection that Danny caught a flicker of movement along the shoreline. Something white flashed silently through the forest, keeping mostly out of sight.

He grabbed the pistol from his waistband.

A deadfall along one edge of the lake allowed him to catch his first glimpse of the beast. It looked like a pale tiger, only sleeker and longer of limb, balanced by a long tail. It carried something limp and pale in its bloody muzzle. Danny feared it was some bit of his father, an arm, a leg.

But as he kept his gaze locked over the barrel of his pistol, he saw it was a large cub, carried by its scruff.

Before the cat disappeared back into the forest, it stopped and glanced back at Danny. Their eyes locked. Its muzzle rippled back and exposed fangs that looked like bony daggers. A hot wetness flowed down Danny’s left leg. A trembling shook through him.

Then in a flicker, the cat vanished back into the forest.

Danny remained with his pistol still pointed. After a full minute, he slowly sank into the center of the boat. He hugged his knees to his chest. He sensed the big cat had moved on, but he wasn’t going anywhere. He would rather starve than ever move closer to shore.

As he watched the forest around him, he could not shake the memory of the creature’s gaze. There had been nothing bestial in those eyes, only calculation and assessment. It had seemed to be judging him, deciding what was needed to reach him.

In that moment Danny knew the broken tree limb had not blocked his way by accident. The cat had done it purposefully, to separate the two men. It had gone after his father first, recognizing the greater threat, knowing its other prey was trapped and at its mercy. With Danny snared as surely as a crab in a pot, he was easy pickings for later.