Amanda Adams (20 page)

Authors: Ladies of the Field: Early Women Archaeologists,Their Search for Adventure

Tags: #BIO022000

By night Max and Agatha reckoned with armies of cockroaches and zingy fleas, but nothing was so bad as the mice. A schedule slowly fell into place. Max got up at dawn and made his way to the excavations. Christie would either go with him or see to the mending of pottery and objects and the labeling of artifacts, and every so often she would make use of the typewriter she’d lugged halfway around the world.

21

Work at Chagar Bazar was conducted from

1935

to

1938

, and during that time, Christie’s involvement with the excavations continually deepened. One account notes that “she had developed into an indispensable member of the team, leaving her own career as a writer in abeyance.”

22

While living and working in the field, she wore several hats. She oversaw matters pertaining to the kitchen and tried to teach the hired hands to cook everything from omelets to lemon curd to soufflés. Her previous work as a nurse put her in a good position to function as a sort of

ad hoc

desert medicine woman; not only did she treat the injured field crew, but she would also give counsel (and aspirin) to the Kurdish and Arab women who came to see her in groups all dressed in their flowing robes and jingling bangles. She supervised the basket boys, the table settings, the shopping excursions, and the purchase of meat. Yet she also began to play a critical role in the archaeology that was being conducted, and her coat pockets were always bulging with the potsherds she loved to collect.

Christie first became acquainted with the process of artifact collection and cleaning while working with Max at the site of Nimrud. Beginning work in

1949

, Max would continue to excavate the site for the next ten years. There Christie spruced up the ancient ivory carvings that were eventually dispersed to museums around the world and even fabricated her own toolkit for dealing with them:

I had my part in cleaning them. I had my own favourite tools, just as any professional would: an orange stick, possibly a very fine knitting needle—one season a dentist’s tool, which he lent, or rather gave me—and a jar of cosmetic face-cream which I found more useful than anything else for gently coaxing the dirt out of the crevices without harming the friable ivory. In fact there was such a run on my face-cream that there was nothing left for my poor old face after a couple of weeks!

23

Agatha Christie pioneered a whole new method in artifact processing: a cold-cream wash. The stuff that smoothed facial wrinkles was equally effective at restoring a fine polish to ivory.

While working, Christie would reflect on the “patience, the care that was needed; the delicacy of touch” that her task required. She devoted herself to archaeology with ease because for her it was a life “free of outside shadows.”

24

Her books would still be written—and she loved to write them—but she surrendered to archaeology’s simplicity, to the uncomplicated and predictable routines of dig life. She didn’t envy the site director’s job—scanning the whole site, putting this and that together, assessing what fit with what and where the next trench should be opened—but rather very much enjoyed the workmen’s lifestyle. Freed from Victorian society, career strains, and a million places to be, she reveled in a simpler life: eat breakfast (hot tea and eggs); walk the site; complete multiple tasks that can be started, finished, and savored with a feeling of satisfaction; have dinner, some wine, and a biscuit; go to bed, and start the next day anew and in the same way. Life on a dig was rigorous and not always comfortable, but it was also devoid of the chaos or social obligations that the naturally shy Christie was inclined to avoid. Field days were the “most perfect” she had ever known.

Standing in a vast and quiet desert landscape, sipping her tea, Christie mused that five thousand years ago, this had been

the

busy part of the world: a thriving region of commerce, trade, and bustling temples. She considered the dainty china cup in her hand and its long evolution: “Here [during their survey of tells] were the beginnings of civilization, and here, picked up by me, this broken fragment of a clay pot, hand made, with a design of dots and cross-hatching in black paint, is the forerunner of the Woolworth cup out of which this very morning I have drunk my tea . . .”

25

Everything in her excavator’s life was akin to a jigsaw puzzle. She fit the pieces together. From reassembling broken potsherds into a whole pot to making connections between the material cultures of then and now, Christie reveled in the hints and revelations of archaeology. It was during this first season at Chagar Bazar that Agatha felt some writerly inspiration as well and wrote

Murder in Mesopotamia,

in which an archaeologist’s wife, highly reminiscent of Katherine Woolley, is murdered.

The second season of work at Chagar Bazar took place in

1936

, and Christie began photographing the dig and the objects recovered. She even made two

16

-mm films, each forty-five minutes long, which recorded both the technical side of excavating and the humorous anecdotes of everyday life on an archaeological site.

26

Her job was to take highly accurate pictures of the artifacts found—each detail in clear relief, with a scale alongside the object. She had her own little darkroom where she would work—and little it was. She wrote that “in it, one can neither sit nor stand! Crawling in on all fours, I develop plates, kneeling with bent head. I come out practically asphyxiated with heat and unable to stand upright.”

27

She craved a little sympathy for the suffering she endured in her chemical-filled hotbox, but Max and the others were far more interested in the quality of the negatives than the photographer’s comfort, or lack thereof.

The second season of work in Syria was also when Max decided to open excavations of two tells simultaneously. They continued their work at Chagar Bazar and began new investigations at the nearby Tell Brak. In between seasons they had returned home for a visit. Max wrote up his archaeological reports while Christie luxuriated in her fill of “Devon, of red rocks and blue sea . . . [her] daughter, the dog, the bowls of Devonshire cream, apples, bathing . . .”

28

Now back in the field, Max and Agatha had the pleasure of a new house to live in at Chagar Bazar (one with a more spacious darkroom), and they were armed with restored energy and six rounds of ripe Camembert cheese. As a side note, the cheese was sadly misplaced and lost in the back of a cupboard, and it wasn’t until the house was pungent with a smell they likened to death that they found the “gluey odorous mass” and decided to bury it in a remote spot, far from the house. It was back to hot tea, hard bread, and eggs.

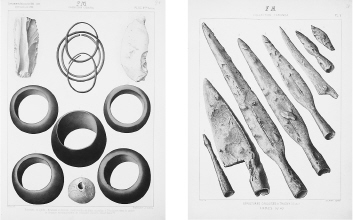

LEFT:

Bronze bracelets, decorative rings, and simple stone tools

RIGHT:

Carved spear points found in a burial site

ABOVE :

The young writer Agatha Christie, 1924

Work at the two tells carried on through a third season, and it was only because war broke out in

1939

that excavations at the Tell Brak, a site Max thought worthy of decades of investigation, would stop. Both Chagar Bazar and Tell Brak were, in Max’s mind, of “extraordinary interest archaeologically, historically and artistically.”

29

Each had its major discoveries. At Chagar Bazar they found a burnt-out palace containing about seventy cuneiform tablets that revealed much about the ethnic backgrounds of the former residents. Tell Brak contained, among many other things, the spectacular Eye Temple, named for the “hundreds of little eye idols of black and white alabaster that lay all over the floors.”

30

Throughout all of the work, Christie was in lockstep with her archaeologist husband; she took part in every aspect of field life for many years afterwards. Christie’s last dig occurred when she was sixty-eight. She and Max were still married and excavating Nimrud.

CHRISTIE’S FAMOUS LITERARY

creation, the detective Hercule Poirot, explains his approach to crime solving in

Death on

the Nile:

Once I went professionally to an archaeological expedition— and I learnt something there. In the course of an excavation, when something comes out of the ground, everything is cleared away very carefully all around it. You take away the loose earth, and you scrape here and there with a knife until finally your object is there, all alone, ready to be drawn and photographed with no extraneous matter confusing it. That is what I have been seeking to do—clear away the extraneous matter so that we can see the truth—the naked shining truth.”

31

Christie’s love and knowledge of archaeology—such a little known fact about her life—shaped much of her writing. You could say that the archaeological process was at the heart of things. Cleaning away the fluff and confusion that clouds a good story, Christie stabbed at the moment of discovery with all the precision of a carefully wielded spade. She honed her trade through the typewriter while hip-deep in the excavation trenches.

All archaeologists are detectives of the past: they reconstruct events from the clues given in crumbling foundations, a lost gold earring, or the fragment of an inscription. To decipher what happened in a place thousands of years ago requires all the skill and cunning of a private investigator. For what is archaeology if not mystery? And where would archaeology be without the deft literary hand of a great mystery writer?

Agatha Christie was never a proper archaeologist per se; she was never a field director and had no academic publications or university affiliation. But she was its champion and its practitioner. She introduced her readers to the thrills of archaeology—its landscape and its ruins. She also brought her readers into the mind of archaeology, inviting them to interpret the evidence and think critically about a sequence of events, about how one thing leads to another. Christie always felt that she and Max were an excellent match, personally and professionally. The mystery writer and the archaeologist had a lot in common.

The field, the Orient, was where Christie felt she belonged. Although she delighted in spending time back home in England, a bowl of cream in easy reach and a white porcelain tub with hot water at her ready, the desert was her happiness. The stuff of her dreams. Archaeology made her life more beautiful than before. One gray winter in London, still enchanted by the memory of soft desert colors, Christie commissioned a special pair of pajamas for herself. Made of crêpe de chine, the bottoms were apricot like sand and the top was blue like sky.

32

The mystery writer who devoted thirty years of her life to archaeological fieldwork wrapped herself up in the beauty of a Middle Eastern desert and slept in the colors of its sunrise.

ABOVE :

The accomplished Dorothy Garrod, 1913