Amber House

Authors: Kelly Moore

“Commander” — our father and

grandfather, who built tree houses

and fashioned a nautical bedroom

and kept up a family history

running back to Jamestown.

Who made our lives possible.

We wish you could have read our book.

I’d been here before.

I was running down an endless hall of doors that opened into other places. I kept repeating the words I had to remember, the directions —

“If you have the chance —”

Endless doors before and behind, only I had grown too big to get through them, or too small to reach the knobs.

“— the chance to choose —”

She skipped ahead of me, glancing back with her solemn eyes, leading me on, her white dress fluttering in wind that blew all around.

“— then take the path —”

I was tired. I felt like I had grown old, running forever. It hurt. But still I had to keep going. Find the right door.

“— the path that leads —”

He was here too, someplace. Behind one of these doors, if only I could choose it. Who? I couldn’t remember anymore. Only the smile. Only his wide white smile …

I was almost sixteen the first time my grandmother died.

It was mid-October. Warm still, like summer, but the trees were wearing their scarlets and golds. Back home, in Seattle, we had evergreens and faded browns. Those absurdly vivid colors along the banks of the Severn River were the first thing I fell in love with — autumn the way it was intended.

It’s hard, now, to remember that first day, like looking at a photo underwater — the image shifting, in motion, never quite in focus. But there’s a part of me that doesn’t forget. And it’s important to tap into that part, to will myself to remember. Sometimes, if I really concentrate, the memories come flooding back. All of them. Beginning to end. Then back again to the beginning. A full circle.

It started at the funeral. We were standing on the hill just west of the house, inside an iron fence filled with tombstones. Everyone in my grandmother’s family had been buried in that graveyard, all the way back to the first immigrants. Gramma had picked out a plot for herself when she was still a little girl. Which gives you some idea about my grandmother’s family and their morbid obsessions.

It was one of the few conversations I’d had with my grandmother that I actually remembered. I was nearly six at the time. She told me about her chosen resting place and then said,

cheerfully, “One day, you’ll be buried there too.” I’d burst into tears.

Ten years later, I found myself clustered with a few dozen strangers on the exact spot Gramma had described to me, beneath the living half of a skeletal tree blasted by catastrophe long ago. The new slab of marble that stood in its shade, waiting to be moved into place, read simply,

IDA WARREN MCGUINNESS ~ AT LONG LAST REUNITED

. We stood in ranks beside the open grave like starlings on an electric wire, listening to the priest remind us there was indeed a “time for everything under the sun.” One old woman dabbed at her eyes with a handkerchief, sniffing loudly. The rest of the group seemed frozen, including my mother. Dad tried to take her hand at one point, but she pretended not to see. Her eyes were focused on something in the distance.

Sammy, my five-year-old brother, was playing hide-and-seek among the headstones — humming the same six notes he always did — and I thought fleetingly of joining him. I guess that sounds like I didn’t have proper respect for the dead. But I’d hardly known my grandmother — I could count the number of times she’d visited us on one hand. And we’d never been to see her here. My mother had always treated Gramma more like a distant acquaintance than a family member. So it was a little hard for me to get caught up in the proceedings.

I felt bad that I didn’t feel bad.

Up the hill a bit, apart from the group, there appeared to be a father-son pair, both blond, bronzed, and sculpted, in matching black suits. I noticed a few of the other mourners covertly pointing them out to one another, and I wondered who they were.

Closer by, on the other side of the rectangular hole punched neatly in the ground, my grandmother’s nurse, Rose Valois, stood with her teenaged grandson, he a full head taller than she. They

were the only two dark faces in a crowd of pretty-much-uniform wrinkled, pasty white. When I glanced at them, the boy looked away, like he’d been caught staring.

My cheeks flushed. I tugged self-consciously at the suitcase-rumpled black sweater my best friend, Jecie, had lent me to wear over an old white blouse. Everything I had on was mismatched and ill fitting — humiliating enough in front of my grandmother’s friends, but it sure would’ve been nice if my mother had warned me a couple of guys my age might be attending.

Mrs. Valois’s grandson glanced back at me. His eyebrows lifted. Now I was the one who was staring.

I forced my attention elsewhere, beyond the fenced-in cemetery. To the fields baked golden. The trees lifting their heads above the bluff from their places along the banks of the river. The distant house crouched behind the thick border of gardens.

Waiting

, I thought. And shivered involuntarily.

The morning air spoke to me. A breeze blew my hair into my face, whispering in my ear. The woods gossiped in hushed voices. Fallen leaves skittered across the ground like furtive animals. I heard an echo of voices, perhaps rising from some boaters on the river.

Sammy and I were the only ones who seemed to notice.

Following the service, the group massed together and headed to the house. All except the father-son pair — I saw them down on the driveway, climbing into a black SUV. I wished I’d gotten a better look at the younger one.

I slipped past the rest of the mourners, scooting out the gate and down the hill, putting some distance between me and the crowd. I wanted to be the first through the door of the family home I had heard about but never seen.

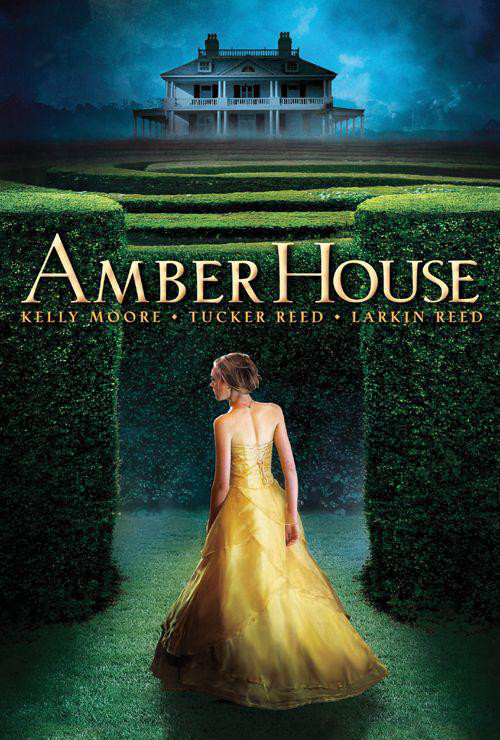

It was one of those places that actually had a name — Amber House. It’d been started in the 1600s as a stone-and-log cabin and had grown a little with every generation, almost like a living thing. Thrust out a wing of brick, heaved up a second story and a third, bellied forward with a new entry, sprouted dormers and gables and balconies. The house was mostly white clapboard trimmed in green, with lots of small-paned windows, and chimneys here and there. Which sounds messy, maybe, but wasn’t. Everything came together into this beautiful whole. All of one piece.

At the entrance, I turned the brass knob, the metal flesh-warm in my hand. With a little push, the door swung smoothly open.

Shadows pooled inside, cool and deep. The air was dust-heavy and silent, empty. I saw a sweep of golden floor, thick Persian rugs, a staircase climbing and turning. Antique tables, chairs, lamps. Oil portraits hanging among folk art of all kinds. I knew without being told that generations of others had lived in this place, and had touched and used and looked upon these same things. It felt somber. Like a place where something was meant to happen. Like entering a church.

Then the crowd caught up with me, dammed into a pool on the front steps by the dumb girl rudely blocking the door, her mouth dropped into a small O.

“You’re in the way, Sarah,” my mother observed.

I pressed my lips together and stepped to the side.

My mother glided in — a black swan leading that flock of black-coated women. She did not look suitcase-frumpy. Even though we’d basically come straight from the airport, not a single wrinkle betrayed the sleek lines of her charcoal suit. She turned and positioned herself to greet the mourners, with maybe the smallest hint of a gracious-but-sad smile shaping her lips. Her guests shuffled past, pressing her hand, seeming a little

baffled by her cold composure. They all stared around them at the house, commenting in low voices, sorting themselves into the rooms that opened off the entryway. Most went through the second door on the left, where the unmistakable clink of china and silverware announced the location of whatever food was being served.

For a moment, I regretted that I hadn’t beaten the crowd to the lunch. My stomach was making those embarrassing empty noises. But I wasn’t hungry enough to wait in a line with twenty white-haired ladies exuding a toxic cloud of Chanel No. 5. So when I saw Sammy scuttling past, I set off after him — my halfhearted attempt to delay the inevitable moment when he would turn up missing, and I would be sent to find him.

He must have sensed I was on his tail, because he doubled his pace. He led me into the living room and the library beyond that, and then through a door to a glassed-in gallery with two archways opening to other wings of the house, closed and unlit.

“Sam!” I hissed as unnoticeably as I could, speed walking behind him. “Sam. Wait up.”

Without slowing, he veered left into the entry again. I next spotted him climbing the stairs. I followed him up, all the while trying to look at everything, trying to take in details. The eight-foot grandfather clock in the bend of the stairs, stopped at 10:37. The posts in the railing, each one different from the rest. The faces of every step, painted with a bible scene. A frame on the wall, covered in black cloth.

The stairs ended on a long landing, where a compass rose was inlaid in the varnished boards of the floor, as if a map was needed to navigate the house. I stood with my hand on the carved newel and looked in all directions. To the north was a wall of windows. South, the long railing overlooking the entry hall. To both the east and west, portals to halls that led off into gloom.

In the western wing, I glimpsed a shadow among the shadows. The back of a stray guest, just standing there, motionless. I wondered why she would be upstairs, nosing around by herself.

“Excuse me?” I called to her. “Are you looking for someone?”

Without a word, without turning, she walked away from me.

“All right, then,” I said, mock cheerfully. What was I? Invisible? “Hey,” I called again, “ma’am?”

She passed through a doorway out of sight.

A little offended at being ignored, I went after her. But stopped after a few steps, and stood there, wavering. Unwilling, unable, to go farther. And just completely surprised at my reluctance.

I shrugged. Shook my head. Let her snoop around. What did I care, really? After all, it wasn’t my house.

I heard Sammy then, before I saw him, materializing out of the shadows in the eastern hall. He ducked through a door. Forgetting about the nosy guest, I started after him again. He’d found a boy’s bedroom completely filled with nautical things — brass lamps, whaling paintings, a harpoon leaning in the corner. All of it orderly and dust free, but I could feel, when I entered, the biding stillness of the room’s disuse.

Sammy was pushing himself in circles in a swivel chair before a desk. The mechanism made small, unpleasant shrieks.

Movement on the floor. “Spider,” I informed him, and lifted my foot to smash it.

“Don’t,” he shrilled, and I hesitated just long enough for it to scurry under a slant-front desk.

“Gross,” I said. “Why’d you stop me?”

“She’s a good mother. She lives here,” Sam said reasonably.

I sighed and shrugged. Another new nut-job notion Sam had got in his head. Whatever. “Listen,” I said, trying to summon

some older-sister authority, “we’re not supposed to be up here, bud.”

He jumped down easily enough. “Okay.” I saw he was clutching some old stuffed animal.

“Put it back, Sammy.”

“This is Heavy Bear. He’s mine now. She don’t need him anymore.”

I grabbed for the bear and missed. Like a pro, Sammy twisted around me, reached the hall, and was off and running. I shot after him. “Put it back!”

“Nope!” he shouted over his shoulder, as his head disappeared down the stairs.

“Sam!” I hissed as I crested the landing — to find a sea of faces looking up at me, slightly aghast. I stopped short, flushing, and decided I was not going to make Sam my problem any longer. Holding my head as high as I could, I floated serenely down the stairs. Then I went to work, mingling. Listening.

My dad always told me that eavesdropping was a bad habit of mine. But it was really more like an instinct. Maybe it wasn’t entirely ethical, but I wouldn’t have learned what little I knew about the important stuff in life if I didn’t eavesdrop every once in a while.

Mostly, the people around me were talking about my grandmother, which I guess is what you’re supposed to do at a funeral. “Such a sensitive soul,” one old woman told another. “I don’t think she ever recovered from the tragedy.”

I jotted that in my mental notebook —

tragedy

— and went back to listening.

Some people talked about the house, as if they had been invited to a guided tour instead of a funeral. “Oldest home in the state, you know; I’m told the antiques are all family heirlooms and priceless.”

“Well, even so, Meredith wouldn’t come today — says she hasn’t set a foot in this house since she was twelve and saw something in the nursery —”

The last speaker spotted me listening to her and gave me a funny look. I smiled at her sweetly, and wandered on.

“I heard her liver failed, but with all poor Ida suffered, it was no wonder she drank.”

Drank

, I noted, and thought,

That explains a few things.