American Experiment (2 page)

Read American Experiment Online

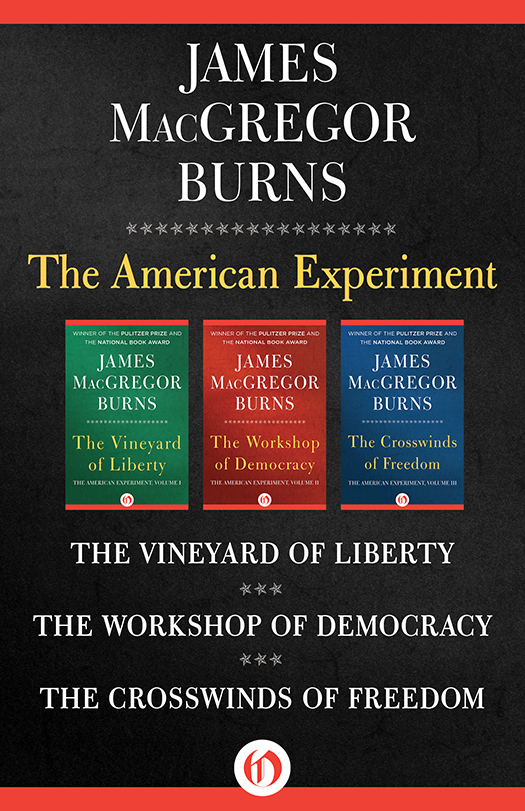

Authors: James MacGregor Burns

PART III • Liberation Struggles

CHAPTER 8

Striding Toward Freedom

CHAPTER 9

The World Turned Upside Down

CHAPTER 10

Liberty, Equality, Sisterhood

BREAKING THROUGH THE SILKEN CURTAIN

PART IV • The Crosswinds of Freedom

CHAPTER 11

Prime Time: Peking and Moscow

FOREIGN POLICY: THE FALTERING EXPERIMENTS

CHAPTER 13

The Culture of the Workshop

PART V • The Rebirth of Freedom?

CHAPTER 14

The Kaleidoscope of Thought

KINESIS: THE SOUTHERN CALIFORNIANS

CHAPTER 15

The Decline of Leadership

REPUBLICANS: WAITING FOR MR. RIGHT

REALIGNMENT? WAITING FOR LEFTY

MEMORIES OF THE FUTURE: A PERSONAL EPILOGUE

The Vineyard of Liberty

James MacGregor Burns

To the vital cadres of history—the archivists, librarians, research assistants, and secretaries—who make possible the writing of history

I sought in my heart to give myself unto wine; I made me great works; I builded me houses; I planted me vineyards; I made me gardens and orchards, and pools to water them; I got me servants and maidens, and great possessions of cattle; I gathered me also silver and gold, and men singers and women singers, and the delights of the sons of men, and musical instruments of all sorts, and whatsoever mine eyes desired I kept not from them; I withheld not my heart from any joy. Then I looked on all the works that my hands had wrought, and behold! all was vanity and vexation of spirit! I saw that wisdom excelleth folly, as light excelleth darkness.

ContentsFrom

Ecclesiastes,

as quoted by Thomas Jefferson, 1816

CHAPTER 1

The Strategy of Liberty

PHILADELPHIA: THE CONTINENTAL CAUCUS

CHAPTER 3

The Experiment Begins

PHILADELPHIANS: THE EXPERIMENTERS

THE VENTURES OF THE FIRST DECADE

SHOWDOWN: THE ELECTION OF 1800

CHAPTER 5

Jeffersonian Leadership

“THE EYES OF HUMANITY ARE FIXED ON US”

CHECKMATE: THE FEDERALIST BASTION STANDS

CHAPTER 6

The American Way of War

“THE HURRICANE …NOW BLASTING THE WORLD”

WATERSIDE YANKEES: THE FEDERALISTS AT EBB TIDE

FEDERALISTS: THE TIDE RUNS OUT

CHAPTER 7

The American Way of Peace

ADAMS’ DIPLOMACY AND MONROE’S DICTUM

VIRGINIANS: THE LAST OF THE GENTLEMEN POLITICIANS

THE CHECKING AND BALANCING OF JOHN QUINCY ADAMS

JUBILEE l826: THE PASSING OF THE HEROES

CHAPTER 8

The Birth of the Machines

FARMS: THE JACKS-OF-ALL-TRADES

FACTORIES: THE LOOMS OF LOWELL

PART III • Liberty and Equality

CHAPTER 9

The Wind from the West

CHAPTER 10

Parties: The People’s Constitution

EQUALITY: THE JACKSONIAN DEMOS

STATE POLITICS: SEEDBED OF PARTY

MAJORITIES: THE FLOWERING OF THE PARTIES

CHAPTER 11

The Majority That Never Was

PART IV • The Empire of Liberty

CHAPTER 12

Whigs: The Business of Politics

CHAPTER 13

The Empire of Liberty

CHAPTER 14

The Culture of Liberty

SCHOOLS: THE “TEMPLES OF FREEDOM”

ABOLITIONISTS: BY TONGUE AND PEN

PART V • Neither Liberty Nor Union

CHAPTER 15

The Ripening Vineyard

“IT WILL RAISE A HELL OF A STORM”

SOUTH CAROLINIANS: THE POWER ELITE

THE FLAG THAT BORE A SINGLE STAR

The Vineyard

A

S AMERICANS GAINED THEIR

liberty from Britain in the 1780s, they had only the most general idea of the great lands stretching to the west. But the scattered reports from explorers had indicated abundance and diversity: a huge central plain and valley drained by a river four thousand miles long; beyond that, an endless series of mountain ranges rising to rocky peaks and interspersed with burning deserts; and then a final mountain range sloping down to a green coastal fringe on the Pacific. There were stories of boundless physical riches in the bottomlands of the rivers, the herds of buffalo stretching for hundreds of miles, primeval forests so thick that migrating geese could fly over them for a thousand miles and never see a flash of sunlight on the ground below.

People living in the thirteen states in the east savored these reports, but they savored even more the diversity and abundance of their own regions. They too could boast of lush valleys and lofty mountain ranges, ample farmlands and invigorating climate. New Hampshire farmers could still be battling blizzards while Virginians saw their first tobacco plants breaking through the red soil. And their own explorers spoke of the matchless beauties of the east. One of these was Thomas Pownall, an eminently practical young Englishman who had helped plan the war against the French and Indians, and in the 1750s had been rewarded with the governorship of Massachusetts.

A tireless traveler along the seaboard and into the mountains, Pownall set about making a map of the “middle British colonies.” A no-nonsense type, he ended his map at the Mississippi and dismissed most of the topography of central Pennsylvania as “Endless Mountains.” But Pownall, in doing his work, was constantly distracted by the charm and luxuriance of the land he charted—the wild vines and cherries and pears and prunes; the “flaunting Blush of Spring, when the Woods glow with a thousand Tints that the flowering Trees and Shrubs throw out”; the wild rye that sprouted in winter and appeared green through the snow; above all, by the autumn leaves: the “Red, the Scarlet, the bright and the deep Yellow, the warm Brown,” so flamboyant that the eye could hardly bear them.

Pownall was eager for Americans to learn from European experience with the cultivation of crops. But he was cautious about trying to transplant

European vines to the American climate, with its extremes of dry and wet, its thunderous showers followed by “Gleams of excessive Heat,” when the skins of “Exotic grapes” might burst. Better, he said, that Americans try to cultivate and meliorate their native vines, small and sour and thick-skinned though the grapes be. Given time and patience, even these vines could grow luxuriant and their grapes delicious.

Some ten thousand years ago or more, big-game hunters from Siberia crossed over the Bering Strait and pushed down along an ice-free corridor through Canada to the grasslands below. These were the first Americans. As they fanned out to the south and east they hunted down and killed countless bison, mastodons, mammoths, and other game with their grooved spears. It took the descendants of these onetime Mongols about a hundred and fifty years to reach the present-day Mexican border and the Atlantic coast, and another six hundred to cross the Isthmus into South America. By that time, they had killed off almost all the big game and had mainly turned to growing maize and other grains.

By the 1780s, Americans living along the Atlantic—immigrants from the opposite direction, the east—had lived with the Indians, as they were misnamed, for a century and a half. Whites tended either to idealize red people as noble savages or to fear and despise them as shiftless, thieving, cruel, ignorant, and Godless. Actually, the Indians were as polyglot and diverse in character as were the European Americans three centuries after Columbus had arrived in the New World with his ship’s company of Spaniards, Italians, Irishmen, and Jews.