American Psychosis (10 page)

Read American Psychosis Online

Authors: M. D. Torrey Executive Director E Fuller

Tags: #Health & Fitness, #Diseases, #Nervous System (Incl. Brain), #Medical, #History, #Public Health, #Psychiatry, #General, #Psychology, #Clinical Psychology

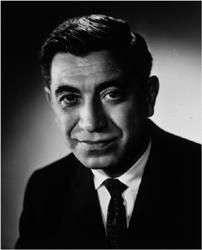

Yolles, age 41 years, had a master’s degree in parasitology and had worked during World War II on the prevention of insect-borne diseases. Following the war he obtained a medical degree and a master’s degree in public health, then took a psychiatric residency at the federal narcotics treatment center in Lexington, Kentucky—the same hospital where Felix had worked. Yolles was a highly intelligent but dour, unfriendly man, said to be “obsessed with organization and the model trains he kept in his basement” (

Figure 3.1

).

18

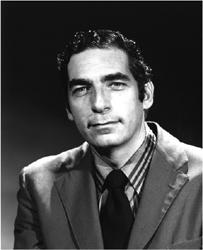

Brown, just 31 years old at the time, had originally been interested in infectious diseases and pediatrics. After getting his medical degree, he took a residency in psychiatry at the Boston Psychopathic Hospital under Dr. Jack Ewalt. While there he also got a master’s degree in public health and moonlighted by working in state prisons. His public health interest caught the attention of Ewalt, who encouraged him to go to work with Felix after he finished. In contrast to Yolles, Brown was gregarious, politically astute, and did not take himself seriously, sometimes introducing himself by saying, “My parents didn’t name me B. S. Brown for no reason.” He was also a concert pianist who had studied at the Julliard School of Music for 3 years (

Figure 3.2

).

19

FIG

3.1 Stanley F. Yolles, M.D., who operationalized the federal mental health program and was NIMH director from 1962 to 1970. In 1977, he admitted that the assumption on which the program had been founded “has not proven to be correct.” Photo courtesy of the National Library of Medicine.

Felix, Yolles, and Brown shared several traits in addition to being psychiatrists. All three were career officers in the U. S. Public health Service and had obtained master’s degrees in public health. Thus, they viewed intended targets of their policies as entire populations, not just individual patients, as public health officials are inclined to do.

FIG

3.2 Bertram S. Brown, M.D., who was the first director of the Community Mental Health Centers program and NIMH director from 1970 to 1977. In 2010, he assessed the federal program as “a grand experiment” but added: “I just feel saddened by it.” Photo courtesy of the National Library of Medicine.

Brown, for example, sometimes facetiously claimed that his real patient was the United States. As public health specialists, all three men also viewed prevention as the ultimate goal of psychiatry.

20

THE DEATH OF THE ASYLUM

The first issue addressed by the Interagency Committee on Mental Health was whether state mental hospitals should continue to be the primary locus of treatment for mentally ill individuals or whether the primary locus of treatment should be shifted to the proposed community mental health centers. The report of the Joint Commission on Mental Illness and Health had called state hospitals “bankrupt beyond remedy” but had recommended that federal funds be invested in improving them. The president of the American Psychiatric Association in 1958 had recommended that state mental hospitals should all be “liquidated as rapidly as can be done in an orderly and progressive fashion.”

21

In addressing the future of the state mental hospitals, it is important to note that nobody on the Interagency Committee had had any significant experience with them. Felix and Brown had been trained in special state research hospitals, called Psychopathic Hospitals, which were not representative of most state hospitals. Felix had worked for one summer in a Colorado state hospital, and Brown had briefly visited several state hospitals in Massachusetts. Yolles had been trained at a narcotics treatment hospital, and there is no evidence that he had even visited state hospitals. The three psychiatrists providing professional input on the future of state hospitals had thus had very little experience with these hospitals or the patients in them. Not surprisingly, none of the psychiatrists was willing to defend the hospitals. Felix envisioned “a new role for the state hospital. . . . [It] will become a psychiatric institute, linked with research centers and medical schools, where techniques for treating chronic patients can be tested.” This was a model similar to the state psychopathic hospital in which Felix had trained. Yolles said that “we all devoutly wish to see the reduction in the size and eventual disappearance of the State hospital as we know it today” and later said that he had truly believed that the hospitals would no longer be needed because community mental health centers would take over their function. Brown recalled that “the power structure of mental health was the state hospital superintendents and the state commissioners. . . . That was the system we had to break in order to have a community mental health system.”

22

One other member of the Interagency Committee emerged as an outspoken opponent of state mental hospitals. Robert Atwell, just 29 years old, had been appointed to the committee as a representative of the Bureau of the Budget because he was the budget examiner for the National Institute of Mental Health. Atwell had a bachelor’s degree in political science and a master’s degree in public administration. His only experience

with mental illness or state psychiatric hospitals was a single visit to a state hospital in Pennsylvania where his grandmother worked as a cleaning woman. He acknowledged in a recent interview that, in retrospect, “I did have some pretty strong views,” some of which were derived from Brown, who became his close friend. In Interagency Committee discussions, Atwell was adamant that federal funds should not be used to improve state hospitals. “He had read the joint commission’s complete studies [and] in his judgment, those studies totally discredited the system of state mental hospitals.” In the end, the committee “agreed to support a federal initiative that would eliminate the State mental institution as it now exists in a generation.”

23

In rejecting in 1962 any significant role for state mental hospitals in the national mental health plan, the Interagency Committee on Mental Health was reflecting ideas circulating at that time in the mental health community. Thomas Szasz’s

The Myth of Mental Illness

and Erving Goffman’s

Asylums

had both been published in 1961. Szasz claimed that mental illnesses did not exist, while Goffman argued that most of the disabilities seen in hospitalized mental patients were a consequence of their having been institutionalized. In 1962 Ken Kesey’s

One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest

was published and immediately developed cult status among opponents of state hospitals. Like Goffman, Kesey portrayed mental patients as fundamentally sane and implied that if they were simply allowed to leave the hospital, they would live happily ever after. Given the popularity of these books and the interest of the Interagency Committee members in the state hospital issue, it seems likely that these books may have influenced them.

The rejection of state hospitals by the Interagency Committee would have profound effects on the subsequent failure of the emerging system. Because no Committee member really understood what the hospitals were doing, there was nobody who could explain to the committee that large numbers of the patients in those hospitals had no families to go to if they were released; that large numbers of the patients had a brain impairment that precluded their understanding of their illness and need for medication; and that a small number of the patients had a history of dangerousness and required confinement and treatment. Nobody could explain to the committee that the state hospitals were playing a role in protecting the public, and in protecting mentally ill individuals from being victimized or becoming homeless. Whatever their other shortcomings, state mental hospitals were still functioning as asylums in the original sense of the term.

THE BIRTH OF THE COMMUNITY MENTAL HEALTH CENTER

Because state hospitals were no longer going to be the primary locus of treatment for mentally ill individuals in the emerging national mental health program, that role would be assumed by the community mental health centers (CMHCs) being proposed

by Felix and his colleagues. According to interviews, Jones, Moynihan, and Fein all “accepted the idea that NIMH knew what programs were needed and, in their own minds, ‘The CMHC program was reasonable.’ “Fein also acknowledged that committee members “were captive of the leadership of NIMH” on this issue. Moynihan had a special interest in making services more available to poor people and keeping families intact, so community treatment, closer to their homes, appealed to him. Robert Manley, the Veterans Administration representative on the committee, thought the CMHC idea “was very good, the best thing so far” and expressed the hope that “it all comes about.” Atwell also found the CMHC idea to be “exciting, different, innovative . . . this was the new frontier,” but he expressed the need for standards of some sort to evaluate the new mental health program.

24

By the time of the Interagency Committee meetings in 1962, Robert Felix had been planning his national mental health program for 20 years and had become an articulate spokesman for it. The community mental health centers, he maintained, would not only treat existing cases of mental illness without the need to send patients to distant state hospitals but, more important, the centers would prevent future cases. This would be accomplished in two ways. First, the CMHCs would identify cases of mental illness in their earliest stages and, by treating them, prevent the full-blown emergence of serious illness. Second, the mental health center staff would work with community leaders to alter social, economic, and cultural factors that were thought to be causing mental illness. As articulated by Felix, the plan presented an attractive if overly optimistic scenario.

The efforts of Felix to promote his national plan for community mental health centers received an important boost in 1961 with the publication of Gerald Caplan’s book

An Approach to Community Mental Health

. Caplan was an English-trained psychoanalyst who was an associate professor at the Harvard School of Public Health, where Brown had studied under him. Caplan’s ideas about mental health coincided closely with those of Felix, Yolles, and Brown. Caplan denigrated state hospitals, saying that “the best of treatment-minded state hospitals perform a disabling custodial function.” He called the idea of early case finding and treatment “secondary prevention” and believed, following classical Freudian teachings, that most mental illnesses are caused by a failure of individuals to resolve early developmental problems. Small problems, if untreated, became neuroses, and these, in turn, became psychoses:

In other words, in order to avoid facing the tensions that his unified, integrated personality would face if dealing with this unsolved problem, he [the patient] just smashes up his personality, as it were. This gives him a psychosis. One of the most typical of these is schizophrenia. . . . If your personality is fragmented you cease to exist from a certain point of view, and cease to feel then the tensions of the unsolved problem. This is a way to escape, and is a quite primitive way. Sometimes there is a complete and absolute disorganization of the personality.

25

Felix was an enthusiastic advocate for prevention and a promoter of Caplan’s ideas. In a Foreword to Caplan’s 1964 book

Principles of Preventive Psychiatry

, Felix extolled the book as “not only a primer for the community mental health worker—it is a Bible.” To prevent future problems, Felix urged mental health professionals to become involved in all of life’s major decisions:

Essential to the effective operation of a preventive mental health program are, first, a population which knows what to do and is prepared to act at the first sign of trouble and, next, services that can give the requested help. People need to know what services are available, and the reasons for utilizing such services, before they find themselves in serious difficulty. They must know why they should seek advice when they plan for retirement, when they consider having a relative live with them, when they prepare a child for hospitalization. All these situations can lead to emotional problems if people are not prepared to cope with them adequately. Most people, however, do not consider seeking professional help until a problem becomes too large for them to handle. They will consult their insurance agents before embarking upon a new insurance program, they will consult their clergyman before getting married, they will do a great deal of research before buying a new car. But very few will consult an appropriately trained person before major problems in their lives get out of hand.

26