Among the Bohemians (27 page)

Read Among the Bohemians Online

Authors: Virginia Nicholson

Tags: #History, #Modern, #20th Century, #Social History, #Art, #Individual Artists, #Monographs, #Social Science, #Anthropology, #Cultural

Putting all these clothes on and taking them all off again dominated one’s day.

Hours were consumed tying tapes, looping buttons, pinning pins, brushing mud off yards of hemline, adding false bits to one’s hair, one’s bosom and one’s bottom, tying ties, shaving and coiffing, gloving and hatting, ribboning and lacing, starching, frilling and goffering… There were better ways to lead one’s life surely, and, as in so many aspects of everyday life, it was artists who broke through the stranglehold of middle-and upper-class conventions.

*

One way of rejecting the proprieties was simply to ignore them altogether, which had the advantage of being cheap, if not entirely cheerful.

Why bother to be smart, when you could cover your nakedness and protect yourself against the elements just as effectively with rags and tatters?

Murger and his Bohemians had bequeathed an honourable tradition on this approach to clothing.

Scènes de la Vie de Bohemè

is full of the pawning, borrowing and conning of overcoats and evening clothes, while back in the garret one dressed in whatever miscellaneous clothes one could scrape together.

There were risks attached of course.

A landlady might not tolerate a tenant who gave her house

mauvais ton

by his scrufFiness, but on the whole Bohemia disdained such squeamishness.

Society would have to endure it if you showed up in odd shoes – and if a friend borrowed your only pair of trousers you stayed in bed.

Nostalgie de la boue

made shabbiness seem romantic rather than degenerate – degeneracy was wanting to trick oneself out in frippery and tight collars – and many artists took an honest pride in appearing undisguised:

Duncan and I have both become very disreputable by now…

boasted Vanessa Bell in a letter to her sister from the Loire valley,

as black as niggers and dusty to a degree.

He has no ties, no buttons to his shirts and usually no socks.

I have lost my only decent pair of shoes and wear red espadrilles,

and my hat flew off yesterday and was picked up by a dog who bit Duncan when he tried to take it from him… The hotels here will hardly take us in…

But I am becoming shameless since I realized that one has only to change one’s conception of oneself into some sort of charwoman or tramp to walk the street comfortably in rags or barefoot.

Why one should ever think decency, let alone smartness, necessary I don’t know, as one has no wish to hob-nob with the other decent and smart.

Caitlin and Dylan Thomas too were defiant in their poverty; for them shreds and patches constituted protest clothing.

Caitlin felt that by wearing down-at-heel, slovenly clothes they could shame respectable people into buying drinks for them.

Even when Dylan’s mother gave Caitlin some money to smarten herself up, she bought one brassière and then blew the rest on a drinking binge with Dylan in Swansea.

But Caitlin confessed that deep down the pair had ‘secret conventional tendencies’, and that their shabbiness was really a front.

Given a chance, and some money, there was something of the Bohemian dandy in Dylan.

For all his slovenliness, he cared enough about clothes to buy a suit and have it dyed bottle-green.

He would agonise between the spotted bow and the long tie for a poetry reading, always ending up with the spotted bow.

He had a mania for shirts, so long as they weren’t his own.

‘I doubt if in my life I have bought as many shirts as he stole,’ recalled Constantine Fitzgibbon.

Dylan could accommodate buttons and ties into his scheme of things, so long as they weren’t dull or anonymous:

As an individual you should

look

individual, apart from the mass members of society… I don’t look a bit like anybody else – I couldn’t if I wanted to, and I’m damned if I

do

want to… Man’s dress is unhygienic and hideous.

Silk scarlet shirts would be a vast improvement.

This isn’t the statement of an artistic poseur; I haven’t got the tact to pose as anything.

Oh to look, if nothing else, different from the striped trouser lads with their cancer-festering stiff collars and their tight little bowlers.

*

Each generation fights a battle against the previous one.

Back in the 1880s the Cox girls, Rosalind Thornycroft’s mother and aunts, had been the belles of Tonbridge society.

Grandmother Cox despaired at her daughters’ refusal to wear bustles.

‘Just a little something, dear,’ she would plead.

But Agatha and her sisters sternly refused, for they were ‘enlightened’ and ‘rational’.

In

artistic circles in the second half of the nineteenth century there was a gradual unfastening and loosening.

Hair began to tumble, dresses to flow, collars and bodices to soften.

The aesthetic movement, with its coloured embroidery and rich colours derived from the canvases of Rossetti, Burne-Jones or Holman Hunt, gathered pace – though this look was still regarded as very ‘advanced’.

Agatha brought up her own children to shun coiffures and stays.

This was in 1900 when the hourglass figure had reached its apogee.

She dressed Joan and Rosalind in Liberty smocks and left their hair loose.

Garters – bad for the circulation – and button boots were banished and replaced with suspenders and ‘nature-form’ shoes.

Rosalind makes it clear that much of this dissenting current in fashion can be attributed to the influence of Pre-Raphaelitism, while the unrestricted, flowing look also had a powerful impetus behind it which came from the dress propagandists of the day.

The Rational Dress Society was founded in 1881, and the Healthy and Artistic Dress Union soon followed.

Such groups took the first faltering steps towards freedom wear, and a fair number of shakers and movers, including Oscar Wilde and Marie Stopes, gathered for enjoyable drawing-room meetings to discuss such popular topics as immodesty, baby clothes, the health benefits of going hatless, and reducing the quantity and weight of undergarments.

Dr Gustav Jaeger was to become the guru of the rational dress movement when he published

Essays on Health Culture

(English translation 1884), in which he expounded his theories about the evils of wearing vegetable fibres next to the skin.

Jaeger’s panacea for all known ills was his revolutionary Sanitary Woollen System, for which he produced natural yarn sanitary shirts, woollen leggings held up by braces, a tight coat, a hat and gloves, all of wool.

Woolly handkerchiefs were also provided.

Bernard Shaw fell for it completely – when kitted out his appearance was by all accounts utterly extraordinary.

Jaeger enjoyed an enthusiastic following among ‘arty’ freaks who did not mind what people said about them, and among others who, finding the woolly look too cranky to contemplate, nevertheless wore their woollen vests just in case.

All these people were minorities, ahead of their time, who challenged the old axiom that

Il faut souffrirpour être belle.

At the turn of the century, particularly in artistic and libertarian circles, the climate was against mortification of the flesh.

Fashionable garments in which you could not move your arms, head or remain standing for long periods made painting impossible.

Thus a fashion-conscious painter was simply a contradiction in terms.

Above all, the liberators turned their attention to foundation garments.

The nineteenth century had already seen a wave of opposition to restrictive underwear among artists and aesthetes.

Ruskin propagandised in favour of ‘right dress’.

G.

F.

Watts even joined the Anti-Tight Lacing League.

In crusading spirit, he draped the uncorseted bodies of his models in Grecian-style robes to pose for his elevated mythological history pieces.

But die-hard Bohemia took things a stage further and often abandoned underwear altogether, as Nicolette Macnamara remembered:

The John girls did not stop at dresses, but probed deeper to underclothes.

The girls suffered bitterly from the cold.

For not only were stockings and closed knickers banished, but wool vests or combinations too.

I shall never forget the horrible chilliness of draughty linen against the skin… We lived with a permanent wind blowing up our legs.

When Nicolette got married to Anthony Devas she found herself conflicted by her longing to impress his bourgeois relatives, and her own unconformable nature:

Now, to conform with the Devases, I squeezed myself into a whalebone corset, donned a severely-fitting tailor-made suit, hat, gloves and shoes.

It was fun to dress up like this for an hour.

But later the clothes restricted my gestures and made me feel sweaty and exhausted.

I stamped on the gloves, ran barefoot and abandoned the tailor-made on the floor.

Fortunately for Nicolette the 1920s saw such a radical alteration in ladies’ fashion that underwear, which as ever determined the female silhouette, became perforce comfortable.

The disappearance of the waist and the suppression of the bosom allowed women to adopt the camisole, a convenient bodice which encased without pressurizing.

This soon evolved into the camiknicker, which, buttoning up between the legs, combined bodice and pants.

The bra did not come in until the end of the twenties.

But most people in the twenties and thirties wore wool next to the skin for eight months a year.

There are those who still remember the overpowering stink of a London Underground train on a warm day.

Meanwhile the dress-reform movement continued to work at persuading men to loosen their collars and relax.

The sculptor and calligrapher Eric Gill wrote

Clothes

(1931) as a diatribe against our unthinking acceptance of fashion’s dictates.

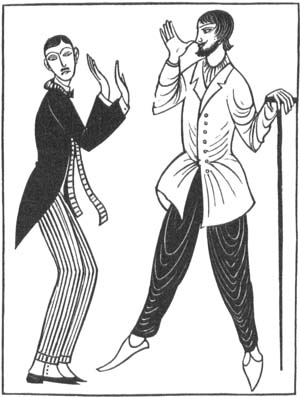

Women were not its only victims; men were condemned to the wearing of tailored suits whose iconography was that of the accountant’s office:

Trousers versus tunics in Eric Gill’s

Clothes

You have a body of skin and bone – ghastly thought!

Cover it up – put thick trousers on its legs and trousers on its arms.

Put, if it be possible, a trouser on its trunk.

Let these things be of a dull and serviceable colour such as will not distract their wearer from his account books… Above all things let these trouserings be dull – dull and drab – drab and sober.

Let there be no suggestion that the man of business has any concern with the passions, whether of love, of sport or of art…

In their stead Gill pleaded with the public to take pride in their bodies, to reject sexual differentiation, and to embrace the only truly universal and beautiful garment – the robe, or tunic.

Gill may have felt encouraged by the sight of emancipated and educated women who, earlier in the century, had had a brief love affair with the jibbah, a shapeless Arab-style robe much favoured by corsetless schoolmistresses at Bedales and vegetarians in Letchworth Garden City.

Gill himself was a lifelong tunic-wearer, with or without underclothes.

This suited his libertinous and exhibitionistic tendencies as well as his rational and aesthetic principles.

His only concession to respectability, if you can call it that, was red silk underpants worn for such gala occasions as the Royal Academy dinner.

Gill’s odd clothing proclaimed him to be special, unconformable, beyond even Bohemian – but his plea for a male tunic was doomed to fall on deaf ears.

*

A more successful campaign was waged by the liberators of the human foot, which, too long imprisoned in agonisingly tight buttoned boots or painfully narrow fashionable high-heeled shoes, ached for release.

Button-hooks were thrown out along with the stays and the collars, and sandal-wearing took on a significance and identification with a certain ideology that it has never since shaken off.

The vegetarian nature lover Edward Carpenter can be held largely responsible for this.

His Utopian approach to the simple life extended to clothing.

Throwing away his dress suit was the first step.

He then dispensed with waistcoats, underlinen, socks, ties and other such superfluities, replacing them with a minimal outfit consisting of woolly shirt, coat and pants.

‘As to the feet, there seems to be no reason except mere habit why, for a large part of the year at least, we should not go barefoot, as the Irish do, or at least with sandals.’ Carpenter was initiated into the secrets of sandal-making by a fellow-travelling back-to-the-lander, and took to the craft with enthusiasm.

One could order a pair from the master for 10s 6d, ‘lower terms for children’.

For long-confined feet sandals were a revelation, and people like Naomi Mitchison were happy to pay over the odds to feel the wind between her toes – for in the twenties it was well-nigh impossible to buy ‘a simple classical sandal’, and she had to have them specially made.

But the look of them was so new, so curious, that sandals became emblematic of a particularly earnest stance towards life.

Evelyn Waugh could spot the type a mile off, living as he did within easy reach of Hampstead Garden Suburb, ‘largely inhabited by people of artistic leanings, bearded, knicker-bockered, flannel-shirted, sometimes even sandalled’.

Sandal-wearing communicated libertarian ideals, a preference for beauty, health and comfort over respectability, and a rejection of materialism.

Despite being expensive, the wearing of sandals was anti-affluence.

So convincingly did the practice convey this message that the French lady curators of Cézanne’s house in Aix-en-Provence were touched to the core by Dorelia John’s plight – her sandalled feet showed that she was clearly too destitute to afford proper shoes – ‘pauvre femme’.