Authors: Rick Atkinson

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #History, #War, #bought-and-paid-for

An Army at Dawn (22 page)

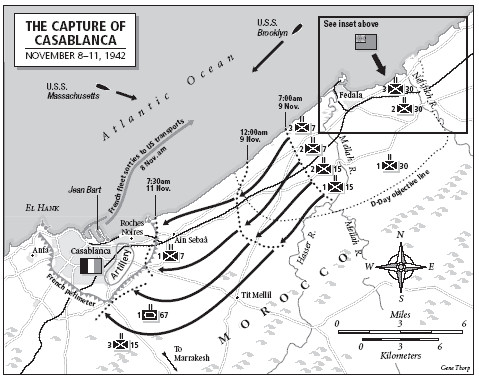

In Casablanca, squads of Senegalese soldiers set up their machine guns with languid gestures. Platoons of spahi cavalrymen in heavy capes cantered from their barracks. Sleepy naval officers hurried toward the port and coastal batteries by Citroën, motor scooter, and bicycle. Allied agents kindled their codebooks. Apart from kidnapping the commander of the Fez garrison out of his mistress’s bed, the insurrectionists had achieved nothing but to give Vichy authorities several hours’ advance warning of possible trouble.

“The sky is dark,” a young Army lieutenant scribbled in a hasty letter before heading to the boat deck, “and everything looks perfect.”

The lieutenant was deceived. Not only was trouble brewing ashore but Hewitt’s ships had thoroughly deranged themselves. Two weeks of flawless navigation collapsed almost within sight of land. Even before half the force peeled off for Safi to the south and Mehdia to the north, disagreement erupted among the captains over the convoy’s precise position. One plot showed that the fleet had actually sailed into the Moroccan hills. The dispute persisted through the early evening of November 7, even though the sky was clear enough to shoot the stars and even after the great lighthouse beacon at El Hank was spotted. The lights of Casablanca burned so brilliantly that one submarine captain likened surfacing seven miles from the city to coming up “in the center of Times Square.”

Despite this irrefutable evidence that land was near, commanders in the main convoy bound for Fedala failed to make the course corrections needed to prevent straggling and align the transports. Just before 11:30

P.M.

, the fleet tried to set itself right with a 45-degree turn to starboard, followed by another sharp turn fifteen minutes later. On this moonless night, many of the red and green lights used to order these maneuvers went unseen. Whistle signals were unheard or miscounted. El Hank and other shore lights abruptly winked out “as though one switch had been pulled.” By the time the drop-anchor whistle sounded, not a single transport could be found in the right location, and some were 10,000 yards—six miles—out of position. “To be perfectly honest,” one naval officer confessed, “I am not right sure exactly where we are.”

Destroyers tacked back and forth to seaward, sniffing for enemy submarines. A light offshore wind carried the loamy scent of land. Above the patchy clouds, Cassiopeia set and the Great Bear rose on his tail. The relentless throb of ships’ engines died away, bringing a silence not heard since Norfolk. Then the metallic rattle of anchor chains broke the spell. Crewmen peeled back the hatch covers, and wheezing donkey engines began to winch cargo from the holds. Bells clanged and clanged again to no purpose discernible to landsmen. In the packed troop compartments, blue cigarette smoke curled around the dim battle lights. Soldiers in green herringbone twill shifted their creaky rucksacks and awaited orders.

Orders came. Men shuffled onto the boat decks. Color-coded cargo nets now draped the sides like spiderwebs. A loadmaster with a bullhorn called to a landing craft sputtering below, “Personnel boat come alongside Red!” Coxswains in yellow oilskin coats and capacious pantaloons eased close, squinting to distinguish red from blue and trying not to foul their propellers in the nets. Officers climbed over the sides, their tommy guns and map cases banging against them all the way down. On some transports, after countless rehearsed departures from the starboard rail, the men were inexplicably ordered over the port side. Chaos attended. Others were told to fix bayonets—until the first man on the net impaled his thigh and was hoisted back on deck as a casualty. The feeble, obscene strains of “4-F Charley” sounded from troops waiting their turn. A veteran of the Great War revived a line often uttered before going over the top: “Don’t harass the shock troops.”

Then the loadmasters bellowed, “Shove off!” Coxswains gunned their engines and sheered away in a green blaze of phosphorescence, studying the heavens with a faint hope that Polaris or Sirius would tell them where to find land.

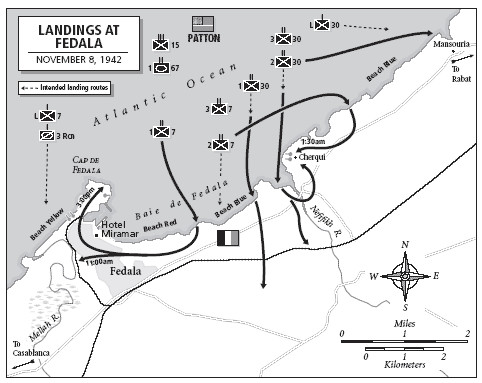

At Fedala, the first wave of twenty-six landing craft headed vaguely east just after five

A.M.

Misguided boats missed the beach and struck a reef with, as an official account later lamented, “indescribable confusion.” Men from the 30th Infantry Regiment struggled toward shore in water chin deep, their hands and legs a fretwork of coral cuts. Dead-weighted with entrenching tools, rifles, grenades, wire cutters, gas masks, ammo magazines, and K rations, those knocked from their feet by the modest waves rarely rose again. The coxswain of a fifty-foot lighter strayed too far in front of a breaker; the bow caught the seafloor 200 yards from the beach and the boat cartwheeled, flinging men, guns, and a jeep into the surf. Only six soldiers emerged alive. Troops flopped onto the sand, shooting wildly at searchlights from the coastal battery at Cherqui while Arabs on spavined donkeys trotted along the water’s edge, scavenging life jackets and canteens. The task force challenge and countersign soon echoed through the dune grass like a taunt: “George!” and “Patton!”

Eighty miles north, at Mehdia, troops from eight transports were to push six miles inland to capture the Port Lyautey airfield. Brigadier General Lucian K. Truscott, Jr., climbed down a cargo net on the

Henry T. Allen

and motored from transport to transport, trying to convince suspicious sailors that he was indeed commander of the Mehdia force. A ragged flotilla of landing craft eventually made for shore with American flags snapping from each stern “like a yacht race.” The crack of gunfire carried across the water, once, twice, then twice more: four soldiers were wounded accidentally by comrades loading their rifles in the boats. Several landing craft snagged on sandbars or capsized as soldiers rolled over the gunwales in their haste to reach land. Sodden bodies washed ashore, facedown in a tangle of rifle slings and uninflated lifebelts. But at 5:40

A.M

., 100 minutes late, the first troops from the 60th Infantry Regiment scrambled unopposed across Green Beach, eyeing the sixteenth-century Portuguese fort that blocked their path to the airfield.

The third and final frontal assault against a defended port in Operation

TORCH

was planned for Safi, 140 miles south of Casablanca. A Portuguese trading post in the age of Columbus, Safi had once earned fame for horse breeding and then as the world’s largest sardine fishery. Now it was an unlovely phosphate-exporting town of 25,000, famous for nothing. Much of the American battle planning was based on a yellowed 1906 French nautical chart, as well as on picture postcards from the Navy’s hoard of tourist snapshots and other memorabilia showing various ocean frontages. Jew’s Cliff, a sheltered beach outside Safi, had been identified through just such a faded postcard; renamed Yellow Beach, it was designated as a prime landing site.

To seize Safi port itself, the Navy chose a pair of ancient destroyers, the U.S.S.

Cole,

which in 1921 had been the world’s fastest ship, capable of forty-two knots, and the U.S.S.

Bernadou.

A secret refitting in Bermuda intended to lighten the vessels and lower their profiles by amputating all masts and funnels had left them “sawed-off and hammered-down.” Each destroyer would carry 200 assault troops from the 47th Infantry Regiment, who received American flag armbands and two cartons of cigarettes apiece with which to buy French amity. Capturing the little harbor would allow Patton to land a battalion of fifty-four Sherman tanks, which could then outflank Casablanca from the south without exposure to the city’s formidable coastal guns.

The Safi assault, known as

BLACKSTONE

, differed in key details from the port attacks at Oran and Algiers. Safi’s defenses were less sturdy than those in the Algerian cities, and American warships stood ready to pulverize any resistance. Also, to avoid alerting the defenders, the attack would slightly precede the beach landings. Commanding the 47th Infantry was Colonel Edwin H. Randle, an Indiana native with slicked hair and a wolfish mustache. “Violent, rapid, ruthless combat is the only way to win,” Randle told his men. “Fire low—richochets may kill the enemy and they certainly will scare him…. Make it tough and make it violent.”

The usual muddle obtained during disembarkation, delaying the attack for half an hour. Loadmasters finally stretched a huge net at an angle from the transport

Lyon

to the destroyers’ decks and rolled the troops down into their comrades’ waiting arms. Only one soldier tumbled into the Atlantic, never to be seen again. At 3:50

A.M.

,

Bernadou

headed for shore, with

Cole

trailing. As the lead destroyer glided toward the granite breakwater, a sharp-eyed French sentry challenged her by flashing two Morse letters: “VH.”

Bernadou

’s captain answered by semaphore with precisely the same signal. The ruse befuddled the defenders for eighteen minutes until

Bernadou

rounded the bell buoy and announced her presence in the harbor at 4:28

A.M.

by firing a pyrotechnic gadget designed to unfurl an illuminated American flag. The stubborn flag stayed furled, and the French opened fire.

Machine-gun rounds cracked overhead and 75mm shells whistled into the water with a smoky hiss.

Bernadou

answered, sweeping the jetties with cannon and mortar fire, then ran aground so hard that her bow lurched thirty feet onto the fish wharf. The assault troops in Company K were flung to the deck.

At sea, two radio messages ran through the American fleet. “Batter up” announced French resistance. “Play ball,” at 4:38

A.M.

, authorized retaliatory fire. With a tremendous roar, the battleship

New York

and cruiser

Philadelphia

complied, aiming at muzzle flashes nine miles away. Mesmerized soldiers and sailors watched the glowing crimson shells arc across the sky before smashing into the shore batteries north of Safi. One of

New York

’s fourteen-inch shells caught the lip of the three hundred-foot cliff at Pointe de la Tour, dug a furrow twenty feet long, then richocheted up through the fire control tower at Batterie la Railleuse, killing everyone inside. Scraps of scalp and the battery commander’s shredded uniform painted the shattered walls.

Unsettled, the troops on

Bernadou

were slow to leave her. They flopped back to the deck with each new shell burst until rousted by their officers and shoved toward the single scrambling net now draped over the bow. Canteens and cigarette cartons snagged in the webbing, leaving soldiers caught like seined fish. The men finally found their valor on solid ground. French troops clattered down a jetty with a small field gun pulled by a donkey; sheets of American bullets sent them fleeing. The

Cole

managed to berth at the phosphate quay at five

A.M.

Company L swarmed ashore, chasing Foreign Legionnaires from the docks and seizing the railroad station, post office, and Shell Oil depot.

Three more waves of infantrymen landed, remarkably, where they were supposed to land. White-robed Arabs crowded balconies above the harbor to watch. An American major later reported to the War Department:

A soldier would snake his way painfully through rocks and rubble to set up a light machine gun, raise his head cautiously to aim, and find a dozen natives clustered solemnly around him. Street intersections were crowded with head-turning natives, like a tennis gallery, following the whining flight of bullets over their heads.

By early afternoon, the invaders held a beachhead five miles wide and half a mile deep. American sharpshooters knocked out three Renault tanks with rifle grenades, then turned the tank guns on a French barracks. Three hundred colonial troops surrendered. A solitary Vichy bomber made a feeble pass at the port; American anti-aircraft gunners, with zeal far eclipsing their marksmanship, shot up warehouse roofs and their own deck booms so vigorously that richocheting .50-caliber tracers resembled “someone trying to cut the cranes with a welder’s torch.”

It was all too much for the French garrison commander. American troops stormed his headquarters at Front de Mer, capturing him and seven staff officers without a struggle. Their combined arsenal consisted of two revolvers. Except for a few snipers, Safi had fallen. U.S. casualties totaled four dead and twenty-five wounded.