An Inheritance of Ashes

Read An Inheritance of Ashes Online

Authors: Leah Bobet

The author gratefully acknowledges the support of the Ontario Arts Council.

Clarion Books

215 Park Avenue South

New York, New York 10003

Copyright © 2015 by Leah Bobet

Jacket illustration © 2015 by Naomi Chen

All rights reserved. For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 215 Park Avenue South, New York, New York 10003.

Clarion Books is an imprint of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company.

Book and jacket design by Lisa Vega

The Library of Congress has cataloged the print edition as follows:

Bobet, Leah.

An inheritance of ashes / by Leah Bobet.

pages cm

Summary: Now that the strange war is over, sixteen-year-old Hallie and her sister struggle to maintain their family farm, waiting to see who will return from the distant battlefield, soon hiring a veteran to help them but, now as ugly truths about their family emerge, Hallie is taking dangerous risks and keeping desperate secrets while monsters and armies converge on the small farm.

ISBN 978-0-544-28111-0 (hardback)

[1. Fantasy. 2. SistersâFiction. 3. SecretsâFiction. 4. MonstersâFiction. 5. WarâFiction. 6. Farm lifeâFiction.] I. Title.

PZ7.B63244In 2015 [Fic]âdc23

2015006823

eISBN 978-0-544-27588-1

v1.1015

For Chandra,

Michael,

and my Philippe,

fixed stars all

PROLOGUE

“HALLIE?” THE VOICE WHISPERED AROUND THE BROKEN

chairs and cobwebs, and I breathed out because it wasn't my father.

Uncle Matthias edged past the snapped spinning wheel, over a pile of fishing nets set aside for mending. “You can come out, sweetheart,” he said. “It's over.”

My ears still rang with Papa's roaring swears, with Uncle Matthias's voice pitched low to cut. They didn't bother whispering anymore when they fought. Marthe had nudged her foot against mine

âI'm right here

âwhen Papa started to growl, but I wasn't half as big or strong as my older sister. When the first dish had flown, I'd run for the smokehouseâand I hadn't looked back.

Deep behind my junk barricades, I swallowed. “Who won?”

“Nobody.” Uncle Matthias's light steps stopped in front of me. “It doesn't matter anymore.”

I scowled. Of course it mattered. I would feel that win or loss in the weight of Papa's footsteps on our farmhouse floorboards, in whether being slow on my chores tomorrow would mean an indifferent smile or a bucket of water across the face. I peeked out from behind the scratched table leg. “Who

won?

”

Uncle Matthias sighed. “Your father did,” he said, and my shoulders sagged with relief. “Come sit with me, kiddo. You'll get splinters down there.”

My uncle's careful hands lifted me from my tangled fortress, carried meâeven though I was much too big for carryingâto Great-grandmother's red brocade stool. He set me down gently, a thin, hardy brushstroke of a man, and I pulled my knees up to my chest. There were new islands in the mess of the smokehouse floor: clothes, tools, two pairs of walking boots.

Uncle Matthias's clothes. Uncle Matthias's tools and boots, scattered everywhere.

“Liar,” I blurted, and he straightened up. “You said it was

over

.”

Uncle Matthias's shoulders slumped. “It is, sweetheart,” he said, so gently. “For good. You and your sister and father are staying. I'm leaving tonight.”

I gripped the sides of the red stool. “You can't.” Uncle Matthias was the one who handled the goats, who could tell Papa

come on, let the girls be

without a day of screaming. Who still gave me piggyback rides along the plowed fields, neighing like the horse Papa'd always promised and never bought.

Who still, after Mama died, loved Marthe. Loved me.

“I'm sorry,” he said, and pulled out a dusty leather pack. “Your father's the older brother. The older child inherits; that's the way it's always been. His name is on the farm deed, Hal. I don't have a choice.”

“He can't make you go!” I argued. My voice swooped and cracked. Uncle Matthias looked down at me, red-eyed, exhausted, and we both knew it was a lie. Tears crept from my eyes: the first drops of a cold winter rain. I buried them against his shoulder. “You

can't

.”

“Hallie, sweetheart,” he said, and wiped my nose with his worn white handkerchief. “Just sit with me while I sort.”

He'd given up. The fight really was over. I nodded, wordless, and he opened his bag.

I watched Uncle Matthias pack as slow as a lullaby. Each seed bag weighed in his palms he fixed in his full, kind attention; each warm sock tucked into the leather pack was another piece of him, vanishing; each shirt left on the smokehouse floor whispered like shed skin. He walked in tighter circles through his scattered worldly goods, and I watched him, my chapped nose buried in white cotton and the smell of his sweat. Both of us just breathing, until the pack was full.

He looked down at his warm winter boots, muttered, “No good,” and closed the pack. It sat between us, bulging, full of fights and love and years: a full quarter of my world, wrapped in a slice of old leather.

“Where are you going?” I asked, too small.

The long, lonely road unwound in his eyes. “South. There are good farms in the southlands.”

“But then you'll come back, right? When it's better?”

Uncle Matthias winced.

He crouched on his haunches so his serious eyes were level with mine. “Hallie. Love. I need you to take care of your sister, okay? Be good to her; be strong. You're the only sister either of you is ever going to have.”

I nodded. I was crying again, crying uselessly, knuckles tight on the stained cotton hanky. Uncle Matthias kissed me gently on the top of my head and picked up the pack. “I love you,” he said clearly, and then slipped out through the smokehouse door.

Behind him, through the eaves and flagstones, the endless silence poured in.

The lamps were lit in the kitchen windows when I trudged back to the house. Light shone jaggedly onto the porch. Papa's voice blasted through the orchard trees, shivered the foundations of our house on the hill.

I clenched my fingers around Uncle Matthias's kerchief.

You have to take care of Marthe,

I thought, and opened the kitchen door.

The kitchen was a shambles. Broken crockery gleamed sharp on the floor, tinkled against Marthe's dustpan as her broom went

shush, shush

across the boards. The table was still uncleared: an overturned chair and four places set for the very last time.

“Leave your shoes on, Hal,” Marthe said, still the stone-faced mountain she became when Papa thunderstormed about. “I haven't found all the pieces.”

I didn't say a word. I didn't have to: Marthe took one look at me and put down the dustpan. “What happened?”

My face twisted. “He's gone.”

Her eyes went wide.

“What?”

“Uncle Matthiasâ”

I wasn't quiet enough. “And where have you been?” Papa snapped from the next room, and my shoulders hunched high.

Marthe's expression flattened. “She checked the coop for me,” she answered, oh so casual. “I thought the latch was loose.”

“Well,

close

it next time,” he snarled, and just like that, just like always, Marthe shouldered his fury away from me. My smart, strong sister, putting the mountain of her fearlessness as shelter over my head.

Take care of Marthe,

Uncle Matthias had said. It was a ridiculous thing to ask. Marthe was ten years older than me. How would I ever be able to take care of her?

And then it struck me finally why Uncle Matthias, the younger son, had told me to make sure I was good to my sister.

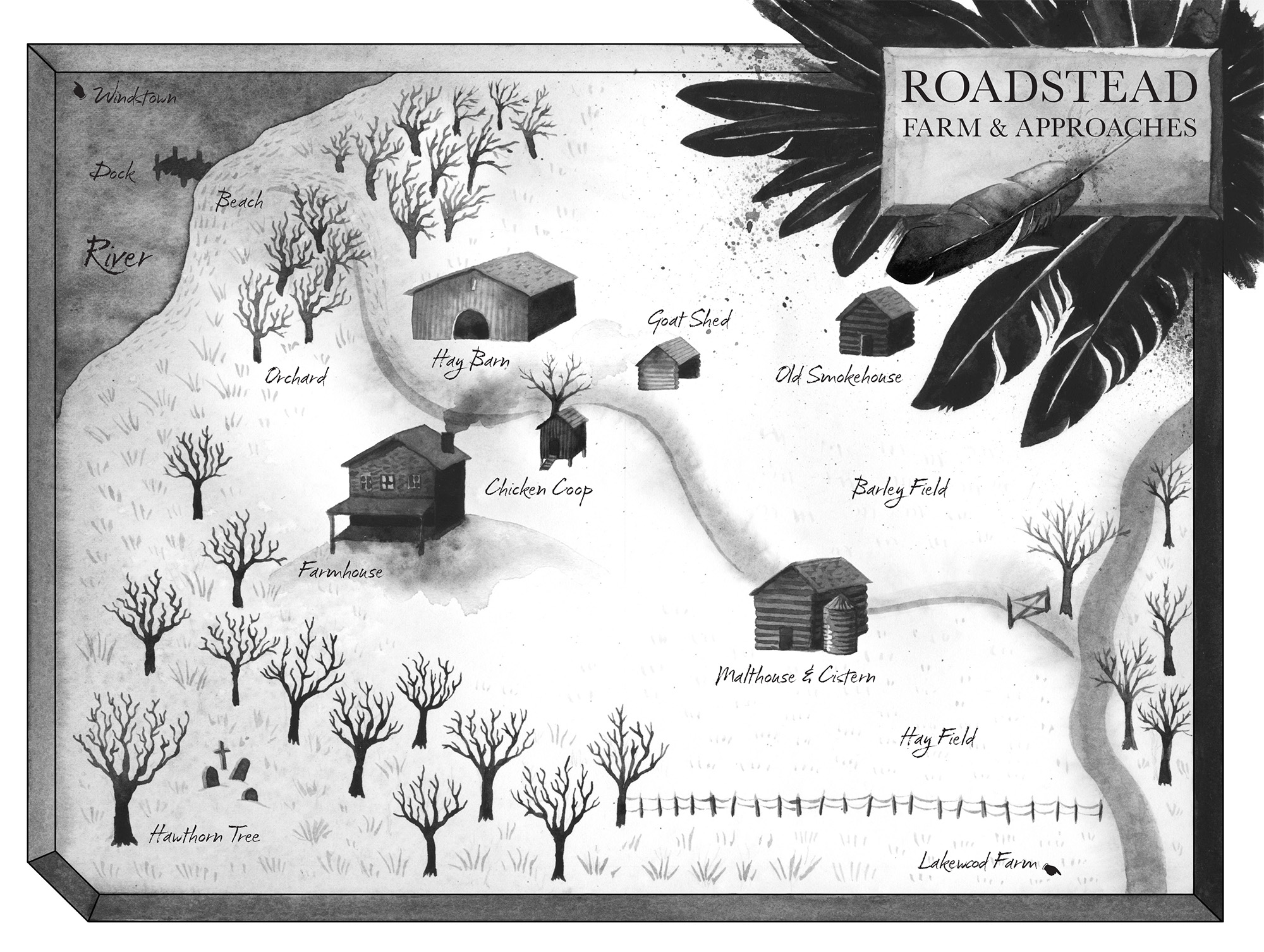

Papa and Uncle Matthias hadn't always hated each other so. And it was Marthe who would one day have Roadstead Farm.

“Hallie?” Marthe said softly. “Talk to me.”

I looked up at my sister's troubled face. And for the first timeâthe first time

ever

âmy mouth shaped the lie: “It's nothing.”

Her frown crinkled as Papa stormed up the stairs. “Here,” Marthe whispered with a new reserve, a crack of worry. “Hold the dustpan for me.”

I crouched on the floor and gripped it tight. Stared at the floor while Marthe's broom worked its rhythm,

shush shush,

to clean up Papa's mess. Upstairs, his footsteps banged. His bedroom door slammed. The walls hummed with his fury.

It was only the three of us now: Papa and Marthe and me. All alone together.

Be good to your sister,

I told myself among the broken dishes.

Don't fight. Be nice. And think hard about what you need in order to survive.

So that when the day came, when it was over, I'd know what to pack.

one

THE BARLEY WAS IN. THE STUBBLE OF IT LAY BENT-BROKE IN

the fields as far as the eye could see, rows of golden soldiers, endlessly falling, from the river to the blacktop road. On a clear evening, with the harvesting done, you could see both river and road from the farmhouse porch: every acre, lined in sunset light, of Roadstead Farm.

So I was the first to see him. Everyone claimed a sighting in the stories that grew up later: a dark man, with a dark walk, striding bravely through the dying grainfields. But it wasn't like that. I was the first to see the stranger when he came to the lakelands, and he stumped up the road like a scarecrow stuffed with stones. Marthe's chimney smoke drifted to meet him, a thin taste of home fires. He caught its scent, his head tilted into the breeze, and hesitated at the weathered signpost where our farm began.