An Old Heart Goes A-Journeying (28 page)

Read An Old Heart Goes A-Journeying Online

Authors: Hans Fallada

Mali, of course, could row, but he did not want Mali with him. He had lost faith in her, she had grown furtive and hostile after her last attack. Since then, everything had changed. He had been conscious of it that evening and all through the night. The young doctor and his medicine had made matters worse and now she

thought of her own condition first of all. She was afraid of these attacks, she wanted him to consider her health before he acted—as if that were the most important thing in the world.

First, Marie’s affair must be cleared up. Then, when they were firmly in the saddle again, Mali might begin to care for her health. Did he care for his own?—not in the very least! Since five o’clock that morning he had been out and about with broken ribs and an aching head—and now he faced a long walk to the cowshed! But he meant to get there.

He wished he could have started at once and avoided the sight of his wife, but he needed a stick to help him on his way, and—

Mali sat motionless in the kitchen, with a strangely vacant face, and did not look up as he entered. He took his stick from the sitting room, and as he went out he asked mechanically: “Is anything the matter?”

She lifted her head with what appeared to be an effort, and in a voice that seemed to come from far away she answered: “What should be the matter?”

“What, indeed!” he shouted, furious with his futile helpmate. “We’ve neither of us time to be ill! Get busy, and don’t be always thinking of yourself.”

He thought for a moment, and then added: “I may as well tell you I’m going to fetch Marie. We shall be back about two o’clock.” But his words had no effect; she was looking down at her lap with the same vacant expression as before.

Muttering a curse he slammed the door and started on his long and weary tramp.

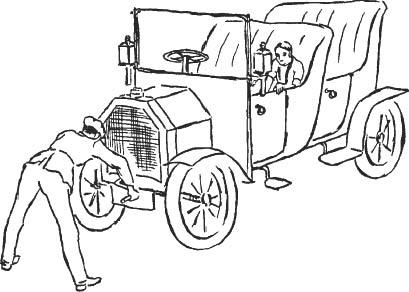

“Get in, Fräulein Thürke,” said Dr. Kimmknirsch, and the girl jumped into the car. Not merely Frau Bimm, but heads from a dozen other windows looked down—at her, at him, and at Herr Tangelmann’s car, a 1908 model.

The doctor struggled with the crank, ran round to the dashboard, adjusted the levers, and then swung the crank again.

Rosemarie was acutely conscious of the faces peering out from behind windows and curtains, and prayed that the engine might start at once, before the expression in those faces turned to scorn.

But Dr. Kimmknirsch had to adjust the ignition several times, and he grew more flushed with his exertions before the engine leapt into life. “At last!” he said, still in high good humor. “These things have their little tricks, you know.”

He released the brake, blew the horn and the car chugged off. It ran smoothly up the street to the railway station. “Easy does it!” said the doctor, as it bumped gently over the local railway line and made for the open country.

“Is this your first trip in a motorcar?” asked the young doctor.

Rosemarie, for some mysterious reason, longed to say “Yes,” but truth compelled her to confess that this was her second ride in a car. “But the other one wasn’t up to much.”

“Why not?”

“It was raining.”

“Oh,” said Dr. Kimmknirsch, and his voice sounded rather annoyed. From then on both kept silent.

They had soon passed the Kriwitz allotments, and were driving between hedges. Rosemarie was disgusted to realize that in ten minutes they would be at Schlieker’s, and then good-by to freedom, friends, and motorcars! Nothing but work, abuse, and misery.

The journey, which five minutes ago she had prayed might start at once, was so near its end that she shut her eyes and began to whimper softly.

For the moment, the doctor did not notice. He jammed on his brakes, exclaiming, “Damn those dogs.”

A volley of barks and yelps followed.

“Bello!” cried Rosemarie. “Doctor—doctor! It’s my Bello—please don’t hurt him—”

“He’s much more likely to hurt us!” cried the doctor, and drove straight at the hedge to avoid the infuriated dog, sounding his horn like a steamer in a fog. The brambles

in the hedge scratched the car, which stopped with a jerk.

“Bello! Bello!” cried Rosemarie, struggling with the door. “We haven’t hurt you, have we?”

The dogs of 1912 loathed cars more than they loathed postmen. Bello could not understand how his beloved mistress could be inside such a horrible contrivance. With flashing eyes and bristling hair he barked frantically at the car and its occupants.

But Rosemarie finally wrenched the door open and jumped out in front of the dog, whose frantic rage suddenly gave way to frantic joy.

“Darling Bello,” said Rosemarie, in a soothing voice. “It’s all right now. Look, the car doesn’t do me any harm.” She stroked both dog and car in turn. “Good car—good dog.”

“Not so very good,” remarked the doctor dryly. “We almost had an accident. He jumped right in front of the wheels, and after all, the hedge couldn’t move. How did your dog get here?”

“He must have come to help Hütefritz.”

“And who is Hütefritz?” asked the doctor, with a ring of professional interest in his voice. “Does he tend sheep?”

“No, cows. He’s Tamm’s cowman. He’s almost as old as I am, and my best friend.”

“Indeed.” The doctor’s interest vanished. “Well, tell him to watch your dog better; he nearly got run over.”

“I have to tend the cows first,” said a voice from the hedge. The doctor and Rosemarie looked up. A face with a tousled thatch of fair hair peered out from among the

brambles, and Rosemarie cried, “Fritz, Philip is all right again!”

“Not quite,” said the doctor, “but he’ll get all right again.”

“Rosemarie,” said the lad, with a barefaced wink at the doctor. “Rosemarie.”

“You can say what you like,” she said quickly. “The doctor knows about everything.”

This time the doctor did not protest against the exaggeration.

Hütefritz eyed the young doctor from his point of vantage behind the hedge. “I hope he isn’t like your Professor,” he observed.

“Hütefritz!” cried Rosemarie angrily.

“Oh, well,” he growled, “you can never tell. I like to know the worst. All right, Rosemarie,” he said, giving himself a shake. “Otsche was here just now. His father has told Paul where you’ve taken your Professor, and Paul’s on his way there now.”

“Oh!” said Rosemarie.

“I can’t leave the cows again. They all got into Gottschalk’s fields yesterday and there’s been trouble with Schoolmaster Schlitz over cutting school—so there was no one I could send.”

“How long has he been gone?” asked Rosemarie.

“An hour, perhaps less. And he’s so shaky on his legs, he can’t make it in under three hours.”

“Whistle to Bello, Hütefritz, and see that he doesn’t get away,” said Rosemarie briskly and Dr. Kimmknirsch was astonished to observe quite a different girl, no longer the pale nervous creature of the night before. “Herr Doctor,

please drive me as quickly as you can to the hut. I know a way to get quite near it. I must warn my godfather that Paul is coming to see him.”

“But your godfather is a grown man,” objected the doctor. “Surely he can manage Herr Schlieker without your help.”

“No!” she cried, “you don’t know what Schlieker can be like, none of you know.”

“Oh, yes, I do; I can very well imagine.”

“And the Professor is so very old, he trusts everyone; Schlieker might very well—”

“Well—what might he do?” asked the doctor, with a superior smile. “Murder him? My dear Fräulein Thürke, you appear to live in a very odd world. We are on the earth, in Mecklenburg—and the worst thing that can happen to anyone hereabouts is to be locked into a coalshed . . .”

He could not help laughing; but neither girl nor boy joined him.

“You don’t know what you’re talking about,” she said crossly. “The Schliekers are brutes who ill-treat and torment little children. And you want me to go back to them just because you can’t imagine what they’re like. No grown-up person can. And I thought

you

would.”

She stopped and struggled with her rising tears.

“What did you think I would do?” he asked.

But the moment passed.

“Very well,” said Rosemarie. “I promised I would go with you to the Schliekers. And I will—Fritz, hold on to Bello. I’ll see what I can do. But I didn’t promise I would stay.”

“Right,” said the doctor firmly. “Then we won’t drive to the hut, we’ll drive to Schlieker’s.”

“Yes,” she said and got into the car.

The engine seemed to understand that everything was settled and started with the first turn of the crank. Bello howled—but after the first turn in the road they heard his lamentations no more.

They said nothing until the car drew up outside Schlieker’s and Rosemarie may not have been the only one who was looking forward to that drive.

“So this is your farm,” said Dr. Kimmknirsch, gazing rather doubtfully at the little house and stables. The autumn, which had stripped the green from the leaves and the leaves from the branches, had laid bare all the defects in the buildings. The plaster had peeled off, the windows were dirty and warped, the fences were in decay.

“It has ceased to be my farm,” said Rosemarie sadly. “People call it Schlieker’s farm now, and so do I—it doesn’t belong to me any more. There’s a room in it that was Father’s, but since the Professor found those torn books, it isn’t Father’s room at all.”

“Cheer up!” exclaimed the young doctor, laying a hand on her shoulder. “Things may look pretty black, but we’ll all keep an eye on you, remember that.”

“You know,” she declared firmly, “I haven’t promised to stay here.”

“Come along,” said the doctor.

They went into the house, and Rosemarie crossed the threshold that she had never intended to cross as long as the Schliekers inhabited that house. The stale moldy smell of the passage seemed to paralyze her senses. What if the sun were shining, what if she had escaped and

found friends like the Professor and the doctor?—that nauseous gloom chilled the very blood in her veins. The leaves had fallen, and the cold dead winter had her in its grip.

“Just what I expected!” said the young doctor’s voice from the kitchen.

Aroused from her numb despair, Rosemarie saw Mali lying on the kitchen floor, with closed eyes, deathly pale, her hands clenched, and her lower lip bitten and bloodstained.

She looked down at her enemy, but her heart remained untouched. The house and her life within it merely seemed darker and more dismal than before.

“She’s unconscious,” said the young doctor, “it’s some time since she had the attack; it will pass over into sleep. Where is her bed? Good—take hold of her and we’ll carry her to it. Pick her up properly,” he said in a sharper tone. “There’s nothing to be afraid of. She may be a bad lot; but she’s ill, and that

isn’t

her fault.”

The girl did as she was told, she helped to undress the sick woman, put the icy body into bed, and arranged the pillows, but the doctor felt her disgust. In a sudden burst of irritation with this obstinate and defiant child, he commanded her curtly, “Go find her husband. Unwilling help is no help at all.”

“He’s at the forest hut with the Professor and he’s up to no good,” the girl replied in a low voice.

“Ah, yes. Well, make sure he has really gone. He might be in the stable. He’s been so badly knocked about that I don’t know how he’s going to get so far.”

The girl walked silently out of the room. The doctor sat and watched beside the sick woman. Her unconsciousness

had turned into a sleep of utter exhaustion in which she barely breathed.

He looked about him. He had had to clear his chair of various odds and ends before he could sit down, and the whole room was in the same filthy, untidy state. Dim light came through greasy windows, and the whole scene was indescribably dank and dismal. Perhaps he ought not to leave a young creature in such surroundings. “Thousands have to grow up in much worse ones,” said an inner voice. “Yes, but when one can prevent it, one should.” “Sick people cannot be left untended.” “That is another matter, Kimmknirsch.” “I shall speak to Schulz, this is not a house, it’s a hovel.” “Well, you brought her here, so you are partly responsible.”

The doctor got up impatiently. Where was she?

He went through the kitchen and the passage into the yard, across the stable, into the garden, and he called her name. Then he hurried back into the house; the sick woman was sleeping as before, but Rosemarie had vanished. She had mentioned her father’s room—was that where she had taken refuge?