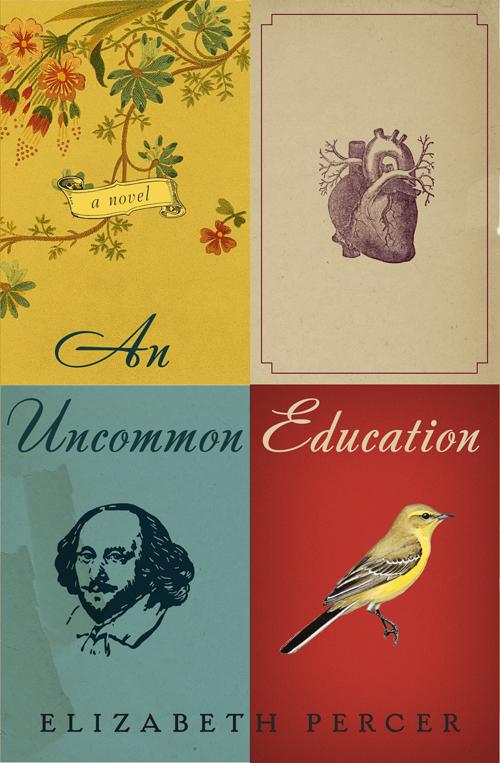

An Uncommon Education

Read An Uncommon Education Online

Authors: Elizabeth Percer

An Uncommon Education

a novel

Elizabeth Percer

for my grandmother,

Sheine Saks,

who might have been a doctor

Contents

Several places mentioned in this novel, such as the John Fitzgerald Kennedy National Historic Site and Wellesley College, have been intentionally fictionalized for the purposes of successful storytelling. Significant inaccuracies regarding the actual physical layout of these locations, for example, will be noted. Representations of actual locations and the cultures therein should be understood to be products of the author’s imagination.

O

n the day after my mother’s death, I returned to 83 Beals Street for the first time in fifteen years. I had stolen something from there when I was almost nine years old and kept it long after my reasons for holding on to it had lost their urgency. I suppose it was one of many talismans, real and imagined, I began collecting around that age to help me believe that what I told myself just might be true. Perhaps the strongest of these convictions, and the one it took the longest to let go of, was that believing that I needed to save those I loved from harm also meant that I could.

Until the afternoon of his heart attack, my father and I spent many afternoons at 83 Beals, otherwise known as the John F. Kennedy National Historic Site. The president had been born in the master bedroom of the modest blue-and-yellow structure in Brookline, Massachusetts, and had lived there as a very young boy. Just after Jack started school, the family moved to a larger, more impressive home nearby, and the Beals Street residence sat largely forgotten for several decades. But in 1967, four years after her presidential son had been assassinated, Rose Kennedy returned to the home, restoration on her mind.

In a completely unrelated set of circumstances, I grew up two streets over from Beals, on Fuller, in an older home that had once been beautiful but whose upkeep my parents could not afford. My mother had inherited it through some unclear chain of events, but she never fully claimed it as her own. I think this had as much to do with its derelict state as it did with the fact that we didn’t have the financial resources to renovate. The paint was peeling on the outside of the house and the interior was deteriorating around the edges into warped wood floors and swaybacked ceilings. I loved it, as children will love anything that is softening into obsolescence, but I knew my parents did not. My mother spent most of her time confined to its master bedroom, and my father was mostly uninterested in housekeeping. He preferred to spend his time with me, developing impromptu lessons based on whatever books we could get our hands on, or developing local excursions for the two of us to take on foot.

The Greater Boston area may appear reserved and unwelcoming to some, but it readily reveals its intimate treasures to those willing to stroll through its meandering streets. There are small blue plaques on gates; diminutive, ancient townhouses with brightly painted doors; tilting cemeteries; hushed museums; gardens so small they only fit the statue they protect. But my father’s favorite of these incidental treasures was the Kennedy house, not least because it had been restored by Rose Fitzgerald Kennedy herself, and by the time I could walk we were regular visitors there.

We always took the self-guided tour, mostly because I loved to push the red buttons that made Rose’s smoothly nasal voice emerge from the speakers on the ceiling. At every room, we’d stop and peer in, each trying to be the first to bring the other’s attention to a newly found favorite object. My father was a master at this game; when I won, it was usually because he’d let me. He never failed to be amazed by the home’s pristine organization and charm, and it was easy to let his wonderment overtake us both. My father wasn’t a simple man, but the reverence he held for the world around us was as striking as a child’s.

I think this was mostly the result of his chaotic and tragic early life: born in Jerusalem in 1935 to parents acutely aware of the tensions in that region, he wandered from home one day when he was six, only to be found a few hours later and brought back safely to a nearly hysterical mother. “It wasn’t only her nerves,” he told me. “She was right to worry. Too many children were disappearing. Too many people. It was hard for anyone to stay calm, never mind a mother with just one child.” Even though the murmurings of murder and great loss had been with them for some time, it was the personal shock of his brief disappearance that inspired his parents to book passage on the SS

Kawsar

from the Suez Port in Egypt to New York in October of 1941.

Because the Axis already controlled the Straits of Gibraltar, the trip took three months and involved sailing around the Cape of Good Hope. Decent conditions on the boat had to be bought, and his family had little money. Yet my father did not see his parents’ deaths as the result of their poverty, as I did at first. Instead, he believed that they came as the result of small, natural choices. He spoke of these details evenly, like he would any matters of cause and effect: “The rats crawled over the bottom bunks; they put me on the top, even when my mother got sick. The food was bad; they let me have the best of it. Medicine was too expensive”—he stared at no one when he spoke of these things—“so they made choices any parent would have made.” He paused. “I would have done the same,” he added.

When I pressed him, as I often did, always hungry for more information than was offered me, he told me that he could hear the rats scampering across the floor all night, that he didn’t sleep for worrying after his mother. “I was too young to argue with my father about who to protect, my mother or me, but I wasn’t too young to be afraid.”

By the time the ship docked in New York, my father’s mother and twenty other passengers had died of dysentery. His father, also infected, died six weeks later. “Don’t be sad, Naomi,” he instructed me from the first telling, taking his thumb to smooth the creases on my forehead. “I was a child. I don’t remember the worst of it. I just remember the good things, mostly. My mother’s clothes carried the scent of the nasturtiums she grew in our backyard in Jerusalem. She always hung our laundry out there to dry. There wasn’t much rain.” He was frowning now; he hated it when I was sad. “And my father had a big beard and a funny face. Not handsome, but nice, with good eyes.” I don’t know if he was telling me the truth and I doubted it. It was far more likely that he would lie to protect me from his pain than that he had no memory of it himself.

The Lithuanian uncle who intended to shelter my grandparents and father temporarily upon their arrival became my father’s grudging guardian. They didn’t even speak the same language; my great uncle spoke Yiddish, Polish, and broken English, and my father had been raised to speak Hebrew. He knew a few Yiddish terms of endearment, but those did not come in handy. The only commonality he and his uncle shared was a desire to avoid my great aunt, Rifka, “a sour woman,” my father said, his own face puckering. “Very sour. They had one book.” He always raised a single finger when he told me this. “A photograph book of Boston Common and the Public Garden. I don’t think they even knew they had it. It was beautiful.” From that time on, my father spent most of his teen years in darkrooms, resurrecting images from pools of black water. By the time he was in his early twenties, he had moved to Boston and set up shop to make his way as a photographer.

He would tell me these stories when I begged to hear them, but they soon created echoes in my mind, bouncing off the much larger walls that guarded the stories he did not tell. In general, he was awkward about his struggles, not fluent in hardship. The only way he would speak of his childhood was to repeat a few, relevant anecdotes, like the fairy tales on the

Let’s Pretend!

records we checked out of the library. I don’t believe these summaries were devised solely to protect me. The first phase of his life was so marked by trauma he was able to detach it almost completely from his later realities; his pain a faulty limb that had been cleanly removed, only to be remembered as a phantom sensation. But he was also able to command the kind of joy that only those who have known deep unhappiness can summon. Since I adored him, I was usually eager to share in his muted entertainments, to watch his face and marvel at how small, strange things caused it to fill with light.

Unfortunately, the Kennedy Birthplace was not reserved for us alone. It was also the place my father took the wealthy out-of-town clients who sought his services as a restorer of ancient photographs, a task that was done by hand until evolving technology made such craftsmanship obsolete. I have often wondered if this work was disappointing to him. He had wanted to bring fresh visions into the world, and had ended up restoring those that could barely be seen. I suppose the life of a struggling artist did not appeal to him. In the 1980s, however, when I was still a girl, my father’s work was in high demand, particularly, and curiously, by elderly Muslim clients from New York and New Jersey. He didn’t make much money in this line of work, but he made enough to support our family of three.

Because the travel time from Manhattan or Bridgewater to my father’s studio was at least five hours, he usually made some attempt to socialize with the men who came to see him, as a way, he would explain, of “making their trip worthwhile.” It seemed lost on him that they might not think of themselves as his guests. And, indeed, with their nervous faces and tight grips on those fuzzy, thin reflections, they were more like escorts than guests—interested only in nursing a tenuous attachment to the ancestors who were, literally, fading away in their hands.

Fortunately, my father was mostly oblivious in social situations and looked forward to a long-distance client visit as though an old friend were coming to town. He planned a handful of excursions for his visitor ahead of time, so that even if it rained he could share something of Boston’s illustrious history with the company he so eagerly anticipated. Since it rains quite often in New England, and since most of his clients weren’t particularly keen on sightseeing, they often chose the easily digestible and walkable Kennedy Birthplace over some of my father’s more ambitious selections.

As much as he enjoyed sharing Boston’s celebrated history with his clients, nothing made these excursions more appealing to him than bringing me along. From a fairly early age, I suspected that even if his clients had been nursing a faint interest in a National Historic Site, they would be extremely unlikely to find their restorer’s daughter of any interest whatsoever, no matter how much her father fawned over her. But it made him happy to bring me, swelled him with pride, in fact, and I liked to see my father standing taller, his head thrown back almost imperceptibly, but to great effect.