Anatomies: A Cultural History of the Human Body (13 page)

Read Anatomies: A Cultural History of the Human Body Online

Authors: Hugh Aldersey-Williams

In 1859, while scholars sat down to ponder the implications of Charles Darwin’s

Origin of Species

, his indefatigable cousin Francis Galton embarked on a systematic investigation of beauty in the British Isles. The young women of London were the most beautiful, he declared finally, and the women of Aberdeen the ugliest.

How did he arrive at his conclusion? Galton, you will remember, was a man given to measurement. During the course of his long career, he sought ways to measure the number of brushstrokes that it takes to make a painting, the parameters of the perfect pot of tea, and the efficacy of prayer (his survey showed that the clergy lived no longer than other professional classes, but then he never asked what they were praying for). To gather the raw data for what he called his ‘Beauty Map’, he would tear a handy piece of paper into the shape of a crucifix. Using a needle mounted on a thimble, he would then prick holes in the paper to log the numbers of ‘girls I passed in streets or elsewhere as attractive, indifferent, or repellent’. The pinholes for attractive girls went into the top part of the cross, those for the average women into the crossbar, and those for the ugly into the stock of the cross. The advantage of this was that he could easily feel for each part of the paper template in his pocket and record his data unseen and unsuspected by whichever town’s female populace he was appraising in so un-Victorian a way. ‘Of course this was a purely individual estimate,’ Galton conceded in his memoirs. But he stoutly defended his scientific method, claiming it to be ‘consistent, judging from the conformity of different attempts in the same population’. The project was never completed; perhaps the prospect of a full survey of British girls was too much even for Galton.

The research was not undertaken simply for fun (or indirectly for gain, as beauty ‘surveys’ put out by cosmetics manufacturers transparently are). So far as Galton was concerned, his data were of little use unless, like cattle, humans could be improved. Darwin had speculated in

The Origin of Species

about the variation of animals under domestication, and this ignited Galton’s interest in variation among the human population. Galton coined the word eugenics to describe this ominous project in 1883, but in a way the basic fantasy whereby the rich, intelligent and fecund would be selected in order to improve the British race had little need of modern science. As Galton noted: ‘it is not so very long ago in England that it was thought quite natural that the strongest lance at the tournament should win the fairest or the noblest lady . . . What an extraordinary effect might be produced on our race if its object was to unite in marriage those who possessed the finest and most suitable natures, mental, moral, and physical!’

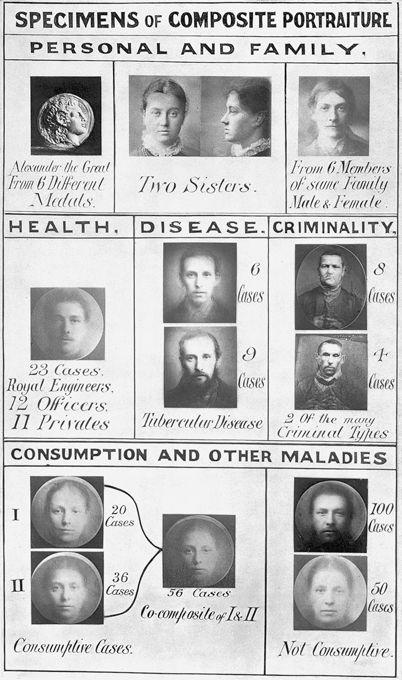

Before the breeding could start, however, there would have to be an awful lot of measurement. This, of course, was Galton’s chief delight, and the innocent reason for his pursuit of beautiful girls. As well as seeking field data on the streets of Britain’s towns, Galton also sought to capture the essence of beauty through other forms of analysis. One technique developed by Galton was to use the new technology of photography in an effort to identify common facial characteristics among sample populations. He tried both ‘composite photography’, layering transparent sheets of facial portraits one on top of another in the hope that the blurry cumulative image would amount to a representative average, and, years later, when this had failed to produce meaningful results, the converse process of ‘analytical photography’, in which faint transparencies of one person in positive and another in negative could be superimposed so that features common to both were cancelled out leaving visible only their supposedly significant facial differences. Both techniques demanded careful preparation, with photographs of the subjects taken at the same size and in the same attitude to facilitate their comparison. Galton gained access to many groups of people distinguished by their deeds or misdeeds or by fortune of their birth. He itemized some of these: ‘American scientific men, Baptist ministers, Bethlem Royal Hospital and Hanwell Asylum patients, Chatham privates, children, criminals, families, Greeks and Romans [apparently considered as a job lot!], Leeds Refuge children, Jews, Napoleon I and Queen Victoria and her family, phthisis patients, robust men, Ph.Ds, Westminster schoolboys’. As it turned out, no firm characteristic appearance emerged from the composites. We have to conclude that this list says more about Galton and his times than about any category of individuals.

The main – disappointing – result of all Galton’s composite photography was to demonstrate that the more individual subjects were added to the composite image, the more any particular facial characteristic tended to melt away. Even the criminals, in whom Galton was particularly interested to identify a facial type that might be useful to the police, looked quite harmless once a few of their portraits were superimposed.

This tendency had an odd consequence in the case of beauty. As Galton frequently observed, his composite photographs tended to be better looking than the individual portraits from which they were made. The criminals looked less criminal, the sick less unhealthy and so on. The good-looking got even better looking, as Galton found when he photographed portrait busts on casts of ancient coins and medals from the British Museum. In one case, he was thrilled to extract a ‘singularly beautiful combination of the faces of six different Roman ladies, forming a charming ideal profile’. The composite in question shows a formidable visage, with a strong, straight nose, a jutting chin and a certain hardness about the lower lip. In quest of beauty, Galton naturally did not neglect the museum’s Egyptian coins bearing the head of Cleopatra. He produced a composite photograph based on five specimens: ‘Here the composite is as usual better looking than any of the components, none of which, however, give any indication of her reputed beauty; in fact, her features are not only plain, but to an ordinary English taste are simply hideous.’

What does this tell us about the beauty of the human face? Rather than beauty’s being in the eye of the beholder, Galton’s research invites us to find something objective about it. A composite face, the combined average of several individual faces, is more beautiful than any of the component faces of real people. Yet it is also an average, with all that the term implies. So is beauty simply blandness? Or is it even, perhaps, something more sinister, the human face with the individuality washed out of it? An important talent of fashion models is to be able to look right in different styles of clothes, and for this a normal face is a good place to start. In 1990, two American psychologists, Judith Langlois and Lori Roggman at the University of Texas at Austin, revisited Galton’s experiment, using computers to create superior composite images of women, and this time also men. By scaling the images so as to superimpose exactly over one another, they were able to eliminate the blurring that had affected Galton’s composites. They then submitted the resultant images to a panel of assessors rather than relying on their own personal judgement. Surprisingly perhaps, they confirmed Galton’s results. Both women and men were judged more attractive as composites, and the more individuals that went into each composite the more attractive it was judged to be, owing to the progressive elimination of facial ‘flaws’ and asymmetries. The authors concluded that their findings were consistent with the pressure of evolution, in other words that we naturally tend to select partners with characteristics close to the mean. It’s as crushingly unromantic a conclusion as any scientist could wish for, and Langlois and Roggman seem duly abashed themselves, referring with oblique self-criticism in the abstract of their paper to science’s perennial search for ‘a parsimonious answer to the question of what constitutes beauty’.

Attractiveness turns out to have advantages well beyond the world of dating. In circumstances where sexual selection couldn’t be less relevant, beauty still has the power to sway our judgement. One typically startling discovery is that attractive persons are more likely to be acquitted at trial.

Is there more than superficial beauty to be read in the face? If criminality could be diagnosed from appearance, as Galton hoped to show, then what of higher virtues? The Greek philosophers believed that character could be read in the face. The most influential figure in reviving this idea – called physiognomy – was the Swiss Johann Kaspar Lavater, a Zwinglian pastor, who published a widely translated collection of essays on the topic in the 1770s. Lavater did his share of sorting ears and noses into types, believing among other things that people who looked like certain animals also had something of those animals’ character. ‘A beautiful nose,’ he suggested, ‘will never be found accompanying an ugly countenance. An ugly person may have fine eyes, but not a handsome nose.’ Lavater himself had a large nose that was almost perfectly triangular in profile, from which we may draw our own conclusions about his self-image.

Above all, Lavater longed to see the face of Christ. The mere sight of it, he believed, would be a divine revelation. It would also provide an ideal template: the more you resembled Him, the better your moral character. The difficulty was that, failing a second coming, there were only artists’ representations to go on, and these of course were based on their own ideas of what Christian virtue looked like, perhaps as glimpsed in the faces of virtuous contemporaries. This teleological reasoning tells us nothing in the end about the divine visage, and there is nothing to say that Christ shouldn’t look like a wrestler or a truck driver rather than the Californian hippie that artists have settled on.

Like its related field of phrenology, physiognomy is now scientifically discredited. Its chief adherents today are those many authors whose characters’ described appearance gives the clue to their behaviour and personality – Charles Dickens’s notorious miser Ebenezer Scrooge, of whom we are told: ‘The cold within him froze his old features, nipped his pointed nose, shrivelled his cheek, stiffened his gait; made his eyes red, his thin lips blue,’ or Gwendolen Harleth in George Eliot’s

Daniel Deronda

, whose ‘self-complacent’ mouth and serpent eyes, described in an opening chapter given over entirely to the arguable matter of her beauty, hint at her later manipulative behaviour, or the unappealing Keith Talent in Martin Amis’s

London Fields

, whose eyes shine ‘with tremendous accommodations made to money’ but without ‘enough blood’ for murder – and the millions of readers who happily go along with the fiction.

Provoked, perhaps, by Galton’s slur on the girls of Aberdeen, Scottish psychologists have been peculiarly active in recent research into our perception of the human face. Computers now allow scientists to manipulate facial images in ways that permit more probing investigation than Galton could ever have achieved with his coins and composites. One particularly striking project, undertaken by Rachel Edwards at the University of St Andrews, involved altering a portrait of Elizabeth I to make it look as if she was using modern cosmetics. Her familiar alabaster foundation – in fact, a poisonous paste of lead white – was replaced by a light tan and an application of blusher. At a stroke, the exercise confirmed the fabled beauty of the virgin queen and provided a convincing demonstration of just how powerful a cultural influence make-up is on our judgement of beauty in appearance.

However, most current studies focus on facial recognition rather than the perception of beauty. Generally, it is more important to be able to recognize a real person than it is to construct an artificial ideal. Galton found this out to his cost one day when he sent some composite photographs he had made of a pair of sisters to their father. ‘I am exceedingly obliged for the very curious and interesting composite portraits of my two children,’ the father wrote back. ‘Knowing the faces so well, it caused me quite a surprise when I opened your letter. I put one of the full faces on the table for the mother to pick up casually. She said, “When did you do this portrait of A? How

like

she is to B! Or

is

it B? I never thought they were so like before.”’ This was an unusually polite response. Most of his recipients, Galton commented ruefully, ‘seldom seem to care much for the result, except as a curiosity’. Galton did not dwell on precisely why people should care about his efforts to make them look more average. But he surely drew the correct conclusion from the rebuffs he received when he added: ‘We are all inclined to assert our individuality.’

Identifying an individual, it turns out, is not simply a matter of presenting an accurate likeness. Philip Benson and David Perrett, also at St Andrews, recorded digital images of various faces, and then exaggerated distinctive features to produce a range of more or less extreme caricatures of each one. When they asked people to select the best likeness from the range, the one they tended to pick out was not the true portrait but a slight caricature.