Anatomies: A Cultural History of the Human Body (21 page)

Read Anatomies: A Cultural History of the Human Body Online

Authors: Hugh Aldersey-Williams

Although it seems likely from the way the gospels describe the incident that Peter would have inflicted a mortal wound on Malchus, the taking of an ear has long been a favourite punishment. The War of Jenkins’ Ear – now an almost forgotten episode in British history – began with just such a forfeit. In 1731, Spanish coastguards boarded a British merchant ship, the

Rebecca

, making passage past Havana on her way home from Jamaica. The coastguard captain sliced off the left ear of Robert Jenkins, the

Rebecca

’s master, returning it to him to keep as a warning of what would befall other British ships that came his way. Jenkins did indeed tell his story to the king’s secretary at Hampton Court when he got home, but the matter lapsed. The actual orifice only became a

cause célèbre

seven years later, when relations with Spain were deteriorating over the matter of slave trading rights in the American territories. Jenkins was called before a committee of the House of Commons in March 1738 and supposedly produced the long-preserved ear in a jar. Jenkins was in fact a reluctant witness, having declined the first summons, and it seems likely that the committee was stacked with Members of Parliament lobbying in favour of war. Detailed records were not made of the committee session, and if Jenkins exhibited anything, it may well not have been his ear but simply a convenient piece of pig meat thrust into his hand as a prop by a lobbyist. Nevertheless, the ear – missing or present – offered a useful symbol of Papist Spanish cruelty to lay before the British public. Britain declared war on Spain the following year.

We can lay the blame for the story on the over-active imagination of the Tory historian Thomas Carlyle, who coined the phrase ‘the war of Jenkins’ ear’ in his monumental history of Frederick II of Prussia, published in 1858. He refers to Jenkins producing ‘his Ear wrapt in cotton: – setting all on flame (except the Official persons) at sight of it’. ‘Official persons’ get the last word, though. The topic of Jenkins’ ear appears as one of the frequently asked questions on the Houses of Parliament website, where it draws the cool response that ‘it seems highly improbable that he would have kept it for seven years!’

Barbaric ear severings continue to the present day. J. Paul Getty III had his right ear cut off when he was kidnapped by Italian gangsters in 1973. His captors demanded a large ransom from the Getty family, who refused to pay. ‘If I pay one penny now, I’ll have 14 kidnapped grandchildren,’ said Getty’s famously mean grandfather. After three months of stalemate, Getty’s captors cut off the ear and sent it, along with a lock of hair, to a newspaper, and reduced their demands. The grandfather reportedly now paid up $2.2 million, ‘the maximum that his accountants said would be tax-deductible’. Four years later, Getty underwent surgery in Los Angeles to create a prosthetic auricle using a segment of cartilage taken from his rib.

The best-known ear in Dutch art is of course the left ear of Vincent van Gogh, a missing part that looms so large it often seems to block our view of the man’s pictures. It has become what the critic Robert Hughes disgustedly calls ‘the Holy Ear’.

A few days before Christmas 1888, van Gogh quarrelled with his friend Paul Gauguin, whom he had persuaded to come and work with him in Arles. The Dutchman brandished a razor before the men went their separate ways. Later, van Gogh cut off his left ear and gave it to a prostitute named Rachel. ‘Keep this object carefully,’ he begged her. What she was to make of the gift is unclear, as is what happened to the ear after that. Van Gogh went home to bed, where the police found him the following morning lying almost unconscious on a blood-soaked pillow. This, at least, is the official version. However, an investigation by two German art historians has opened up another possibility. Hans Kaufmann and Rita Wildegans believe that it was Gauguin who inflicted the damage using a sword during the fight, and that the two artists subsequently agreed on the (slightly) more plausible cover story. It is, after all, Gauguin’s written accounts that provide most of the evidence for the official story.

What this still doesn’t explain is why, if it was van Gogh’s left ear that was severed, it is the right ear that appears extravagantly bandaged in his

Self-Portrait with a Bandaged Ear

done a month or two later. Another self-portrait from 1889, produced when the artist had somewhat recovered his mental health, shows him in three-quarters profile from the left side – with ear intact. When newspapers reported Kaufmann’s and Wildegans’s theory, several of them showed the portrait with the bandaged right ear while blithely referring to the severed left ear in the accompanying article.

The explanation, of course, is that van Gogh painted himself from his image in a mirror. In both paintings, he wears the same greatcoat, which is buttoned at the top. The button is on the left and passes through the buttonhole on the right – the fashion for women’s coats. Men’s coats normally button the other way round, so this confirms that van Gogh worked from a mirror image. So does a sketch done by his friend Dr Gachet, showing van Gogh on his deathbed with the damaged tissue around the left ear clearly visible.

Using a mirror seems a straightforward enough thing to do. Self-portraitists had been using mirrors since they became generally available, which, perhaps not coincidentally, is when the genre began. Rembrandt, for instance, was suddenly able to paint larger self-portraits when he acquired a larger mirror. But the practice raises a deeper question about identity. Doesn’t it matter that we are being shown left for right and right for left – if not to the viewer, who may be none the wiser, then at least to the artist himself? In this very obvious optical sense, the painting does not represent the artist’s true self. Jan van Eyck, painting Canon van der Paele, shows us the ugly truth of his damaged ear. Vincent van Gogh, painting himself, shows us a reflection of the truth, but perhaps a deeper truth, too. The common artist’s deceit of using a mirror is made to appear less a matter of unthinking procedure and more a matter of deliberate assertiveness by the striking asymmetry of his injury. It was relatively unimportant to van Gogh, as it was to so many self-portraitists before him, that he leave us with a mirror image of his ‘true’ self. It was more important that he show us his injury: in January 1889, the self-harm

is

the self-portrait.

What are we to conclude about the ear from this little gallery? We have seen the ear as a site of ugliness and imperfection, as a symbol with many meanings, as an object of punishment, as a love token and as a badge of self-loathing mutilation. It is the plasticity of this modest appendage that enables it to perform so many roles. The outer ear is composed entirely of soft tissue and cartilage. There is no supporting bone. This means that it can be deformed and reformed, cut away and replaced. It is an exemplar of arbitrary human tissue.

In this capacity, the flesh of the auricle may stand in for the whole body, either dead or alive. The Mimizuka monument in Kyoto – little known even among Japanese – contains the heaped-up severed ears of Koreans taken as trophies during the Japanese invasion in the 1590s; ears were taken in lieu of heads simply because so many were slaughtered, up to 126,000 according to one source. The removal of an auricle from a living subject leaves only a small wound and cuts no major blood vessels and so is unlikely to lead to death. It too may stand for the whole person, as we have seen with the unfortunate Jenkins.

The function of this fleshy efflorescence in assisting hearing seems almost marginal – it is the inner ear that does the real work. The auricle comes across as a bit of a perk – an erotic bonus perhaps, somewhere useful to hook spectacles, or simply an ornament. It is flesh as a sculptural medium, a notion encouraged by its delightfully baroque curves. The crinkles that complicate the outer curve of the ear arise, incidentally, from an embryonic feature known as the six hillocks of Hiss. Some of these hillocks tell almost forgotten stories. A malformation called Darwin’s point, for instance, is the vestigial remnant of a fold that once allowed the auricle to flap closed over the opening of the ear canal, while another of the hillocks was once associated with criminality, and is still sometimes the focus of requests for cosmetic surgery.

These ideas flourish in contemporary art and science, where the ear remains a locus for demonstrating technical prowess. As the art critic Edwina Bartlem observes: ‘Strangely enough, artificial ears are powerful signs of tissue culture engineering and biotechnologies more generally.’ The iconicity of the ear was only reinforced in 1995 when Charles Vacanti of the University of Massachusetts and Linda Griffith-Cima at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology successfully engineered animal tissue in the shape of a human ear on the back of a live mouse. The growth had no hearing function. It was simply tissue that grew, nourished by the mouse, on a polyester scaffold that could have been made in any shape. So why an ear? One purpose of the experiment was to show that cartilaginous structures could be grown of a kind that in future might be suitable for use in ear transplants. The sculptural delight of the shape may also have played a part. In addition, the instant recognizability of an ear immediately enabled lay people to see the potential of the technology. Perhaps, too, the scientists hoped to generate a little shock value. In any case, the mouse-with-the-ear-on-its-back swiftly became a symbol not so much of the potential to engineer replacement human body parts as of the kind of silly thing scientists can get up to when left to their own devices.

In 2003, an Australian group called Tissue Culture & Art, based at the University of Western Australia, began work with the artist Stelarc on a piece called

Extra Ear

¼ Scale

that seems at once to parody and to extend this work. The idea was to grow a quarter-scale replica of Stelarc’s ear from

human

tissue. Oron Catts and Ionat Zurr, the artists behind Tissue Culture & Art, wrote of the original exercise in Massachusetts: ‘We were amazed by the confronting sculptural possibilities this technology might offer. The ear itself is a fascinating sculptural form, removed from its original context and placed on the back of a mouse; one could observe the ear in all of its sculptural glory.’ Stelarc has since gone on to construct a life-size ‘ear’ grafted on to his own forearm. The procedure required surgery first to grow extra skin on the arm and then to insert a porous polymer scaffold that would bond with the new tissue in the appropriate shape. Surgeons have performed similar operations as a part of procedures to rebuild damaged ears. Stelarc, however, has gone beyond cosmetic surgery with a disturbing attempt to supplement the body’s quota of functioning organs. The finished

Ear on Arm

incorporates a microphone as well as additional electronics to transmit sound and communicate via a Bluetooth connection, allowing people in remote locations to hear what the ‘ear’ is ‘hearing’; ‘an Internet organ,’ says Stelarc.

The French philosopher René Descartes spent the most fruitful period of his life in the Dutch Republic, where he moved frequently between the academic centres – Franeker, Dordrecht, Leiden, Utrecht – developing his knowledge of mathematics, physics and physiology, before settling down in the remote seaside village of Egmond-Binnen to write out his new theory of everything. In 1632, he was to be found in Amsterdam; it is quite possible that he was among the audience at Dr Tulp’s anatomy demonstration.

Descartes was no armchair philosopher. His radical ideas about the human body as a kind of mechanism, and the intellectual rigour that would soon turn him into an adjective – Cartesian – were based on first-hand observation and his own experiments. On one particular occasion during the 1630s, he took the unusual step of procuring the eye of an ox in order to understand more precisely the intricacies of vision.

He described his results in an essay entitled

La Dioptrique

, a work that is neglected in comparison with the one that prefaced it, the illustrious

Discourse on the Method of Rightly Conducting One’s Reason and Seeking Truth in the Sciences

, which includes the famous aphorism

cogito ergo sum

– I think therefore I am. Descartes published

La Dioptrique

in 1637 at Leiden, accompanied by two additional volumes on meteors and geometry, making three major parts (and the preface) of what was to have constituted a grand

Treatise on the World

, other chapters of which he was forced to withhold when they were suddenly rendered obsolete by Galileo’s discovery that the earth revolves around the sun.

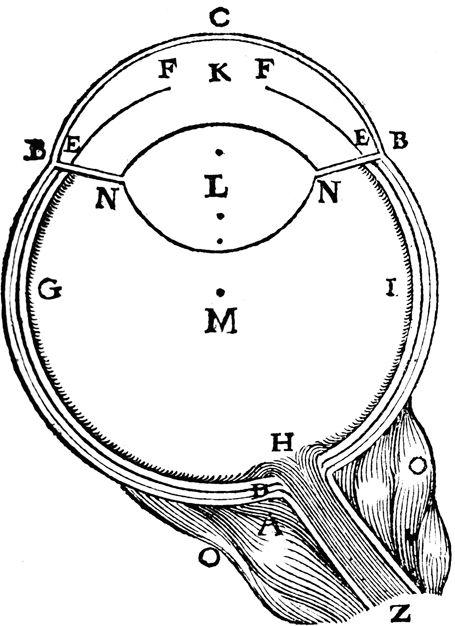

He begins his discussion of the eye with an optical diagram. ‘If it were possible to cut the eye in half without spilling the liquids with which it is filled, or any of its parts moving about, and the plane of the cross-section passing right through the middle of the pupil, it would appear as it is shown in this figure,’ he tells us. Already, it is interesting, in view of his philosophical subject matter, to note that Descartes is drawing our attention to something that, for the very good reasons he gives, could not actually be seen. The text that follows describes each of the parts that Descartes has labelled in his diagram – the hard outer skin of the eye, a loose second skin ‘hung like a tapestry’ inside the first, the optic nerve and its branches, which mingle with fine veins and arteries across the inner hemisphere of the eye in a fleshy third layer, and three zones of different transparent ‘slimes or humours’ filling the interior of the orb.

How do these liquids and nerves enable us to see? Descartes took up his ox eye and a scalpel and carefully peeled away the outer layers from the back until it was transparent. Then, he positioned the eye facing outward in a hole at a window in a darkened room. He placed a thin piece of white eggshell at the back, where he had cleared the surface. The bright scene outside was faithfully reproduced upside down and in miniature on the eggshell screen. As he wrote in his account of the experiment: ‘you will see there, not perhaps without admiration and delight, a picture [

peinture

] which will represent in a strictly artless way in perspective all the objects which are outside.’

This internal image is formed by optical refraction, which explains why it appears upside down. The image of ourselves that we see when we look closely into the black centre of somebody’s eye, on the other hand, is formed by reflection. This little effigy has inspired our word pupil, which derives from the Latin

pupilla

, meaning a little doll, as well as the charming seventeenth-century colloquialism ‘to look babies at’ somebody, which means to look adoringly into their eyes, a reference not as you might think to the urge to procreate with that person, but to the sight of this diminutive human form. This part of the eye was not called the pupil until the 1660s, however; Descartes describes it using the French word

prunelle

, meaning a sloe.

I decide to try to repeat the experiment. My prize-winning local butcher, Crawford White, is very tolerant of my occasional odd requests, and does not turn a hair when I ask for eyes of a bull or cow, although he explains he cannot get these for me, presumably because of the dangers of bovine spongiform encephalopathy. But, he tells me, he could have some pigs’ eyes ready for me if I come back later in the day. At home, I gingerly open the little bag I have been given and find four pairs of eyes rolling around inside. Each eye is about the size of a grape, rather smaller than a bovine eye, which I worry may make the dissection tricky. Three-quarters of the spherical surface of the eye is covered by a white layer like a large icecap. The stump of the severed optic nerve protrudes from the midst of this expanse. The front of the eye is clear with glossy black and grey depths.

I pick out one of the eyes and begin by trimming away the flesh and fat that clings to it. Then, squeezing the eye slightly between my fingers in order to give it a firm surface, I begin to cut into the white membrane that protects the clear orb within. It is very tough, and I am nervous of applying too much pressure and piercing the inner membrane with my scalpel. Almost immediately, the worst happens and a gelatinous liquid oozes out of the eye. I take a second eye and start again. The same thing happens. I change my tactics, and try to shave the white tissue away rather than cutting through it. This works better, and by the fourth attempt, I have scraped away enough at the back of the eye that I can just perceive light through the remaining film.

At last, I take the eye over to a large cardboard box that I have prepared. I have cut an eye-sized hole into the front. At the back, I have cut out the shape of an upward-pointing triangle and positioned a bright light beyond it outside the box. I position the eye in the hole ‘looking’ through the box towards the light, and then I position my own eye directly behind, looking at it. I am thrilled to see a hazy image of the triangle pointing downward projected onto the white film.

‘Now, having thus seen this picture in the eye of a dead animal, and having considered the causes, one cannot doubt that it forms a similar whole in that of a living man.’ The eye, Descartes had discovered, works like a camera obscura, projecting an inverted image of the outside world on to its back surface. In his

Dioptrique

, he provides a ray diagram showing how this happens. It is both clearer and more beautiful than the diagrams I find in those few of today’s anatomy textbooks that concern themselves at all with the physics of how the body actually works. In another version of the diagram, Descartes’s illustrator has drawn the small bearded head of a man in miniature looking up at the back of the eye where the inverted image is formed. He seems like an astronomer gazing at the heavens.

This idea of a homunculus standing at the back of the eye sets up a paradox. For what does this little man gaze

with

other than

his

own eyes? Does the soul have eyes as well as the man? It is, says Descartes, ‘as if there were yet other eyes in our brain’. Somehow, anyway, this image is converted into a form that can be transmitted through the brain to the soul, which Descartes locates in the pineal gland. This pea-sized organ is now known to be responsible for the release of the sleep-promoting hormone, melatonin. This gland is indeed sensitive to light, as the release of melatonin is triggered by darkness, but it is not in fact involved in visual perception.

Descartes’s picture of the eye was incomplete as well as flawed – it offered no explanation of our ability to judge the size of things that we gain from having our two eyes spaced apart, for example. But it was revolutionary because it appeared to bring sight – the most mysterious, even mystical, of our senses, linked after all with ‘visions’ as well as straightforward seeing – within the scope of a mechanistic view of the body. Touch, taste and smell involve our physical interaction with the substance of the world. Even hearing, through the time it takes for a sound to reach us, is easy to imagine as some

thing

arriving at our ears from a distant source. Now sight could be comprehended in a similar way.

As I have pigs’ eyes to spare, I decide to round off my experiment by trying to view an eye in cross-section, producing in reality the diagram that Descartes warns cannot be seen, by taking a bold slice through its equator. I approach the task with trepidation and some sense of horror. Luis Buñuel’s image of a man slicing into a woman’s eye with a cut-throat razor flashes through my head, even though I have never seen the surrealist film from which it comes. (Like Descartes, Buñuel actually used a calf’s eye, as is all too apparent in the shot when I finally see it.) In the moment before I wield the scalpel, I understand why it is that organ donors are often more reluctant to let go of their eyes than they are even their hearts.

Yet when I actually cut into the eye, my perception changes. My knife is not sharp enough, and I cannot help squashing the eye out of shape as I depress the blade, spilling the contents. The worst over, my horror dissipates, to be replaced by fascination. Although they have not held in their correct positions, I can see that there are three distinct transparent liquids: a small quantity of a watery liquid, a larger quantity of liquid like jelly that has not quite set, and, slipping out from between them, a clear bead about the size of a pea. Though soft, it holds a definite shape that is oblate, and flatter on one side than the other. These are the aqueous humour, the vitreous humour and the lens, whose different refractive indices allow us to focus images of the outside world. Animal viscera are revealed as pure Cartesian mechanism. What began as an anatomical investigation has ended as a physics experiment.

Eyes are an important element of our identity. They are said to be the window on the soul. Even in fables of werewolves, the transformed man retains his human eyes. Yet what is it about them that conveys individuality? Colour is their most distinctive attribute. Eye colour was a feature of Alphonse Bertillon’s system of identification for the Paris police, and has been routinely included in official identity records since the introduction of standard passports, where it supplements the likeness offered by a black-and-white photograph. The popular idea that eye colour is important seems likely to be reinforced once again with the introduction of iris-scanning technology to replace document checks.

This is doubly ironic because colour is not what is scanned. Iris scanners in fact use infrared light to detect unique

patterns

in the iris. And, although the iris is named after the Greek word for rainbow, it may come as a surprise to learn that there is no distinctive colour present in the eye in any case. The colours that we perceive do not arise from different pigments, but are what is known as ‘structural colour’ – an illusion of colour produced by an effect of interference between light rays that is also found in butterfly wings and iridescent bird feathers. All eyes contain a certain amount of one pigment, melanin. I found dark flecks of this pigment floating in the humours when I cut into my pig’s eye. It is the variation in the levels of this pigment, together with the light-interference effect, that gives rise to the entire range of eye colours that we cherish. With progressively less melanin present, the eye can appear dark or light brown, hazel, green, grey or blue.

Francis Galton was curious to learn what eye colour had to say about heredity. He built himself a travelling case with sixteen numbered glass eyes of different colours. The eyes were set into a sheet of metal moulded in such a way as to give each of them eyelids and an eyebrow, an alarming surrealist touch when you first open up the case. Galton needed to be sure that the colour labels he chose from among the ‘great variety of terms’ used by compilers of family records were the ones important in nature. He didn’t choose brown or blue, as we usually do, but categories of light and dark, splitting those with ‘hazel’ eyes into both camps. He then compared children with their parents and grandparents, whipping up his usual storm of statistics, but finding nothing more noteworthy to say at the end of it than that both blue eyes and brown eyes are observed to persist down the generations.

The ultimate answer to Galton’s question about heredity came in 2008, when a team of (largely blue-eyed) researchers at the University of Copenhagen discovered a mutation of a particular gene that regulates a protein needed to produce melanin. Babies are often blue-eyed at first, even when born to brown-eyed parents, because this protein is yet to be released to its full extent. According to Hans Eiberg, who led the research, his genetic discovery suggests that all blue-eyed individuals alive today can trace their ancestry to one original Ol’ Blue Eyes, who was the first to undergo this mutation, between 6,000 and 10,000 years ago.

A mere accident in nature, maybe eye colour doesn’t have quite the significance we thought in culture either. Becky Sharp in

Vanity Fair

has green eyes, Anna Karenina has grey, James Bond, blue. The worse the novel, it seems, the more important it is to be exact in description. To wit, Judith Krantz’s

Princess Daisy

has ‘dark eyes, not quite black, but the colour of the innermost heart of a giant purple pansy’. But many of the most famous characters in fiction prove surprisingly elusive when it comes to eye colour. Mr D’Arcy merely thinks Elizabeth Bennet has ‘fine eyes’ in

Pride and Prejudice

. Julian Barnes devotes large portions of his novel

Flaubert’s Parrot

to the matter of Emma Bovary’s eyes, berating a (real-life) critic who had triumphantly spotted Flaubert’s supposed sloppiness in describing her eyes variously as blue, black and brown. It doesn’t matter, Barnes suggests; or rather it does, but not in the sense that we must know the colour of her eyes in order to identify, or identify with, the heroine. Emma’s eyes are whatever colour Flaubert chooses to make them for reasons of his own at that point in the narrative. In

Tess of the D’Urbervilles

, Thomas Hardy also dodges the question of the colour of his heroine’s eyes, which are ‘neither black nor blue nor grey nor violet; rather all those shades together, and a hundred others, which could be seen if one looked into their irises – shade behind shade – tint beyond tint – round depths that had no bottom; an almost typical woman’. If an author wants us to believe that his character is everywoman, then being vague about eye colour is a good way to start.