Anatomy of Fear (5 page)

“Cálmate,”

I said.

The truth was sometimes I didn’t know who I was—my Grandma Rose’s

tatelleh

or my

Abuela

Dolores’s

chacho.

Hector Lavoe’s

La Voz,

the voice, was playing in the background, but only because I’d brought the newly reissued CD of the Puerto Rican salsa singer’s groundbreaking 1975 album with me. Otherwise it would have been Mozart or Beethoven, which I still couldn’t get used to hearing in Julio’s house.

I looked around at the leather couch, Persian rugs and antiques, two floors of a brownstone on Ninety-fourth between Fifth and Madison. Ironic, I thought, Julio living the good life only minutes away from the mean streets of El Barrio where he’d grown up.

“This place is too good for you, man.”

Julio made a fist, tapped his heart, and slid into the street talk

of his youth. “Don’ worry, brothuh, even though I’m at the top, you still my main-mellow man,

mi pana.

”

Jess rolled her eyes. “Must you guys always act like teenagers when you get together?”

“Yo,

mira,

I think so.” Julio winked at me.

We’d been buddies forever. Julio’s aunt lived in the same tenement as my grandmother and he’d hang out there because it was better than the peeling paint and roaches of the project where he lived with his single mom, who worked day and night to keep a roof over their heads. We met one day in the stairwell, Julio hiding out so his aunt wouldn’t see and tell his mother that her son was smoking dope at age eleven, and he gave me a toke, my first. When I recovered from the coughing fit we started talking, bonding over the music of Prince and Carlos Santana. From that day on we were brothers.

A

fter that I started going uptown all the time. El Barrio was an ugly ghetto, but compared to where I lived—the Penn South apartments on Eighth Avenue and Twenty-fourth, which was filled with old people and had about as much life as a funeral parlor—it was exciting. My parents didn’t like it, but I told them I was in search of my Spanish heritage. Of course that was bullshit. What Julio and I were searching for was alcohol and drugs—and we found them.

Julio would buy weed off the local salesman, some guy who hung around his junior high, then we’d get stoned and go lie around my grandmother’s apartment watching TV, playing Nintendo, and laughing. She was always asking

“¿Qué es tan chistoso?’’

which would make us laugh even harder.

Julio asked if I was okay and I nodded, but a piece of my past

had started to play and I couldn’t stop it. I was back in my parents’ apartment on Eighth Avenue and Twenty-fourth Street, reliving that night, seeing it all—my room with its posters of Che and Santana, but mostly the look on my father’s face.

It was inevitable that he would find out. Maybe I even wanted him to. I thought I was cool and dangerous, bringing shit home with me, grass and crack pipes, not bothering to hide them well. Ironic, you might say, me discovering drugs and my father being a narc with the NYPD. When he found the stash he went ballistic.

Don’t you know what I do for a living? Don’t you know every week I find kids like you dead, OD’d? What’s wrong with you?

He went on like that for a long time, face bright red, veins in his forehead standing out in high relief. He wouldn’t stop until I told him where I’d bought my stuff, then he stormed out in search of the guy who was turning his son into a junkie. I was scared shitless. I called Julio, told him to warn the dealer, and asked him to meet me uptown.

I

came back to the moment, rubbing my temple.

“Headache,

pana

?”

“It’s nothing.”

I’d started getting headaches after things went bad. The doctors couldn’t find anything wrong with me, so my mother sent me to a shrink. He told me it was displaced anger or guilt and I told him to shove it and never went back. But it wasn’t anger or guilt that was giving me a headache right now. It was a combination of my past and the nonspecific dread I’d felt earlier in the day that was still with me. I couldn’t shake either one of them.

Julio started talking about a lawsuit he was working on, and got all excited; Julio, the big real estate lawyer, it still surprised me.

“Hey, remember when we used to say you’d be a musician and I’d do your CD covers?”

“That was a long time ago,” said Julio.

“You mean you wouldn’t swap your career for Marc Anthony’s?”

“

¡Nipa-tanto!

Not even for that gorgeous wife of his, JLo.” He looked at his wife. “Who’s got nothing on Jess. And for your information, I love my job.” He smiled, zygomatic major muscles flexing his cheeks to the corners of his lips, muscles tightening around the eyes that accompanied a genuine smile, which was impossible to fake. It was true: He loved his job and loved his wife.

“And what about your dream of becoming an artist?”

“I

am

an artist,” I said.

“Yeah,

mira,

a cop artist,” he said, but smiled. “Jess, have I ever told you Nate was top of his class at the academy, got every award, special this, special that?”

“Yeah, I think you told her about a dozen times.” I looked at Jess and sighed. “Do not believe everything your husband says. Let me correct that. Do not believe

anything

your husband says.”

It was simple, why I gave up actual police work after six months on the street. I couldn’t take it. Period. I couldn’t take the sour coffee or the sour pimps or the sour prostitutes or the petty thieves or anything else. I hadn’t gone into it for the right reasons, and when it didn’t reward me by assuaging my guilt, I folded. End of story.

The baby started to fuss and I lifted him out of the bassinette and cooed him into silence.

“Yo,

pana,

you missed your calling. You should have been a wet nurse.”

“Be quiet,” said Jessica. “You’re a natural father, Nate.”

Julio’s eyebrows slanted up, his mouth down, “action-units” that suggested sadness or anxiety, and I wondered why.

Jess leaned across the table. “Nate, there’s this great girl at the office, Olivia—”

“Olivia? For Nate? No way.”

“Why not? She’s pretty, and—”

“She’s all wrong. Not Nate’s type.”

“What’s Nate’s type?”

“Not Olivia.”

“Hey, guys,” I said. “I’m still in the room, remember?”

“

¿Y qué?

Who cares?” said Julio, and laughed.

They went on like that, discussing this woman or that one as a possible match for me because when you’re single, couples feel it is their duty to get you married. I just listened while the baby fell asleep against my chest.

At the end of the night Julio was still wearing that sad-anxious expression and I wanted to ask him what was wrong, but he got me in a bear hug before I could.

T

he call from Detective Terri Russo had been a surprise. There was something she wanted to show me. A drawing, I guessed. Or one she wanted me to make. She hadn’t been clear, but what else could it be? I crossed a path between the maze of buildings that made up Manhattan’s Police Plaza, rubbed a hand across my chin, and thought maybe I should have shaved.

The sky was a bright cobalt blue that only New York City gets in winter, but I was sick of the cold and looking forward to the spring that you never believe will come in March. I dug my hands deeper into the pockets of my old leather jacket. It wasn’t really warm enough, but I didn’t own an overcoat and had been wearing the jacket for so many years it felt like a second skin.

I glanced up past the buildings that made up Police Plaza to the place where the World Trade Center had stood. On the day of the attack I had been down here working on a sketch with a witness to a bank robbery when we heard the first plane hit. We came outside and saw the flames and smoke, and like so many others who had come out on the street thought it had been some horrible freak accident. But when the second plane hit twenty minutes later, there was no mistaking it. From where we stood, I could see the

bodies leaping and falling. It was so unreal I thought I had to be dreaming, it had to be a nightmare, that Jesus or Chango had gone insane, that I was in hell.

About a week after the attack I read a piece in the

New York Times

by a psychiatrist who said denial was a necessary part of human existence and I took refuge in that, and understood what he meant because I’d practiced it from a fairly early age and had, apparently, become very good at it.

So now I focused on a handful of crocuses that had bravely pushed up through a light dusting of snow in the center of the walkway, and took them as a hopeful sign that spring would come and that all was right with the world, that Inle had gone to work healing, as my grandmother would say. I wanted to believe that someone was thinking about healing, but even now, more than five years after the towers had come down, I could not stop worrying about landmarks exploding, poison gas in the subway, or an avian flu pandemic. I started chewing a cuticle, a habit I developed after I’d quit smoking for the third time.

I thought about my first and only meeting with Detective Russo over a year ago, as I emptied my pockets to go through the metal detector. Good-looking but tough, at least that’s how she’d seemed when I’d handed over the police sketch I’d done for her, which had led to her capturing a perp, which in turn led to her promotion, or so I’d heard. She never told me. It wasn’t like I was expecting a gift-wrapped thank-you, but a call wouldn’t have killed her.

T

he door was ajar and Russo was pacing back and forth. I caught a few glimpses of her tight jeans and black tee. She was letting her hair down, combing her fingers through it, and it reminded me of

a pastel by Degas, one of the artist’s

Bathers

. She was cinching her hair into a ponytail when I tugged the door open.

Detective Terri Russo was even better looking than I remembered, high forehead, straight nose, her full lips reminiscent of the actress Angelina Jolie.

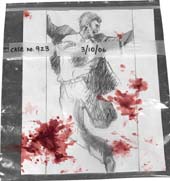

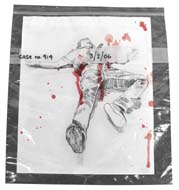

“Sorry to drag you all the way downtown.” Her voice deeper than I remembered, tinted with an outer-borough accent I couldn’t quite place, maybe Brooklyn or Queens. “But the lab isn’t finished with these.” She indicated some sketches laid out on the desk that had already caught my attention. “Homicide Analysis has looked them over and Forensics too, but there are more tests and full workups to come.” She was talking in a rush, obviously worked up. “I asked you here because I need a good set of eyes on these. Maybe you can see something in them neither the lab nor the technicians can.”

I waited, but she didn’t add any details. “So what do you think?” “They’re not bad.”

“I wasn’t looking for a review. I want to know if you think they were made by the same person.”

“Well, that’s not what you asked, and I’m not a mind reader.”

“Really? I’d heard just the opposite. You’ve got a reputation.” A small grin passed over her lips, but didn’t set up camp. “So, is it?”

“The same artist?”

“Yes.” She was rapping her fingernails against the edge of the desk.

“Okay if I take them out of the bags?”

She nodded and handed me a pair of gloves. I put them on, slid the drawings out, and came in for a closer look.

“The mark-making technique looks the same in both drawings, one just a bit looser than the other,” I said. “Drawing is like handwriting.” I took another minute going from one sketch to the other, while Detective Russo kept up the annoying fingernail tapping.

“You could take something for that,” I said.

“For what?”

“Your nerves.”

Russo’s upper lip registered just a bit of disgust at my comment, so I guessed she didn’t think it was funny. I said I was sorry and went on to tell her a bit more about the pencil strokes I was

looking at, pointing out how they both used the same sort of angled stroke.