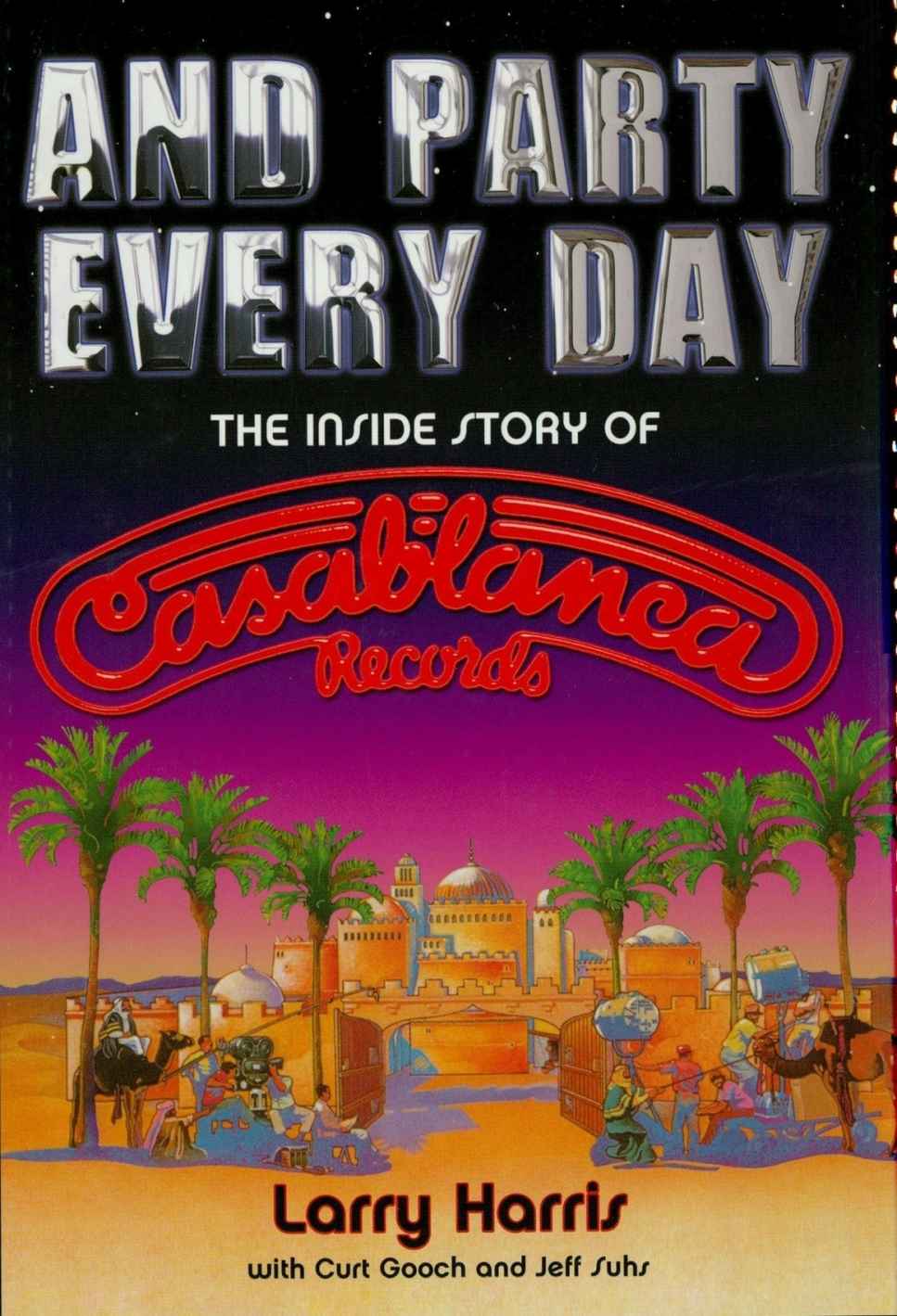

And Party Every Day: The Inside Story of Casablanca Records

Read And Party Every Day: The Inside Story of Casablanca Records Online

Authors: Larry Harris,Curt Gooch,Jeff Suhs

BOOK: And Party Every Day: The Inside Story of Casablanca Records

4.82Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

Copyright © 2009 by Larry Harris

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, without written permission, except by a newspaper or magazine reviewer who wishes to quote brief passages in connection with a review.

Published in 2009 by Backbeat Books

An Imprint of Hal Leonard Corporation

7777 West Bluemound Road

Milwaukee, WI 53213

An Imprint of Hal Leonard Corporation

7777 West Bluemound Road

Milwaukee, WI 53213

Trade Book Division Editorial Offices

19 West 21st Street, New York, NY 10010

19 West 21st Street, New York, NY 10010

CASABLANCA is a trademark of the Universal Music Group family of companies and is being used under license.

Printed in the United States of America

Book design by Lynn Bergesen

Typography by UB Communications

Typography by UB Communications

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Harris, Larry Alan, 1947-

And party every day : the inside story of Casablanca Records / Larry Harris, with Curt Gooch and Jeff Suhs.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references, discography, filmography, and index.

9781617748745

1. Casablanca Records—History. 2. Sound recording industry—United States—History. 3. Scott, Neil, 1943-1982. 4. Popular music—United States—History and criticism. I. Gooch, Curt. II. Suhs, Jeff. III. Title.

ML3792.C37H37 2009

781.640973’09047—dc22

2009032038

Table of Contents

1 The Beginning Of A Beautiful Friendship

2 Woodstock (No, Really, I Was There)

3 A Converted Buddahist

4 Leaving The Nest

5 Our First Kiss And A Ride On The Mothership

6 Kiss∼off, America!

7 Steppin’ Out And Comin’ Home

8 Here’s Johnny!

9 The Germans Are Coming!

10 Alive To Love You, Baby

11 The New Casbah

12 Breakthrough

13 The Mothership Arrives

14 The Skyrocket Takes Flight

15 The New Bubblegum

16 La~la Land

17 Writing The

Billboord

Charts

18 Cracks In The Casbah

19 Last Dance

20 Now And For The Rest Of Your Life

2 Woodstock (No, Really, I Was There)

3 A Converted Buddahist

4 Leaving The Nest

5 Our First Kiss And A Ride On The Mothership

6 Kiss∼off, America!

7 Steppin’ Out And Comin’ Home

8 Here’s Johnny!

9 The Germans Are Coming!

10 Alive To Love You, Baby

11 The New Casbah

12 Breakthrough

13 The Mothership Arrives

14 The Skyrocket Takes Flight

15 The New Bubblegum

16 La~la Land

17 Writing The

Billboord

Charts

18 Cracks In The Casbah

19 Last Dance

20 Now And For The Rest Of Your Life

To Neil Bogart, my mentor, friend, and second cousin

(once removed, whatever that means)—

a true creative force in the entertainment industry,

whose energy and gutsy approach to everything

from music and film to philanthropy

made the world a better place.

(once removed, whatever that means)—

a true creative force in the entertainment industry,

whose energy and gutsy approach to everything

from music and film to philanthropy

made the world a better place.

While, like the rest of us, he wasn’t perfect,

he certainly made his mark

on the lives of countless millions.

he certainly made his mark

on the lives of countless millions.

Preface

A long time ago, I met a man who was painting a building. It was a small building, and he asked me to help him paint it, so I did. As we were painting, people would walk by. A few of them looked a bit crazy, just like us, so we asked them to help, and they did.

And then the building started growing. The more we painted, the more the place grew. The more it grew, the more crazy people showed up to help us paint it.

The building was becoming a palace, but it wasn’t necessarily a “nice” palace. Soon, it was filled with things you wanted so desperately you could taste them. Things that you got and ended up wishing you didn’t have. Money. Cocaine. Weed. Booze. Sex and mountains of Quaaludes. Success and excess at every level. And, worst of all, the promise of more. Within five years, the palace took up an entire city block, and the sign out front read “Casablanca Records.”

My boss, my cousin, my mentor—a complete fucking genius named Neil Bogart—was the guy who started us all painting. “Painting the building” was his mantra, his way of saying that if you looked successful, you

were

successful. Perception was reality. He was right.

were

successful. Perception was reality. He was right.

But the story of Casablanca was about more than just Neil. It was about the 1970s. I take that back—it wasn’t about the 1970s, it

was

the 1970s. It was the story of the music industry in the go-for-broke Me Decade. In those five years, we built our beloved Casablanca from a four-person, one-act outfit into a corporation with 175 employees, more than 140 artists, and an Academy Award–winning motion picture division.

was

the 1970s. It was the story of the music industry in the go-for-broke Me Decade. In those five years, we built our beloved Casablanca from a four-person, one-act outfit into a corporation with 175 employees, more than 140 artists, and an Academy Award–winning motion picture division.

I was along for the ride, sometimes serving as the train’s engineer, but for the most part, I was the one in charge of stoking the fire and clearing the tracks so that the unstoppable steam engine called Casablanca could keep chugging up the hill. We all believed in that bedtime story about the little engine, and, no matter the odds, we always knew we could, we knew we could, we knew we could...

Larry Harris

July 2009

Prologue

“Even in the bacchanal of 1970s Los Angeles, the drug

and promotional excesses of Casablanca Records stood

out. In a period when cocaine use was probably at its

peak in the music business, Casablanca set the pace

...”

and promotional excesses of Casablanca Records stood

out. In a period when cocaine use was probably at its

peak in the music business, Casablanca set the pace

...”

—Encyclopedia Britannica

July 21,1978

Casablanca Record & FilmWorks Headquarters

8255 Sunset Boulevard

Los Angeles, California

Casablanca Record & FilmWorks Headquarters

8255 Sunset Boulevard

Los Angeles, California

“You stupid fucking idiot!”

I was pissed. I was so pissed I was shaking. I was on the phone with Bill Wardlow, the head of

Billboard

magazine’s chart department, holder of one of the most powerful positions in the music business. I had just called him a stupid fucking idiot. And I wasn’t even close to being done.

Billboard

magazine’s chart department, holder of one of the most powerful positions in the music business. I had just called him a stupid fucking idiot. And I wasn’t even close to being done.

“You can’t do that! We had an agreement! I don’t care if their record is selling better than ours—that has nothing to do with it! Give them No. 1 next week. We discussed this yesterday, and you told me we would have No. 1! You have to change it back. I already told Neil that we would be No. 1.”

I wasn’t just pissed, I was scared. I had promised to deliver

Billboard’

s No. 1 album in the country to Casablanca, and now a done deal had been yanked from me—from us—at the eleventh hour.

Billboard’

s No. 1 album in the country to Casablanca, and now a done deal had been yanked from me—from us—at the eleventh hour.

I was intimately familiar with all the steps that had to be taken to get the top album in the country, and screaming at the head of

Billboard’

s chart department was way, way down the list. Yet it was a step I was taking. I knew that they weren’t going to let out the chart information for another two hours. They could still change it. I wasn’t going to stop screaming until they went to press.

Billboard’

s chart department was way, way down the list. Yet it was a step I was taking. I knew that they weren’t going to let out the chart information for another two hours. They could still change it. I wasn’t going to stop screaming until they went to press.

“I couldn’t care less if Al Coury already knows about the numbers! Did he pay you off in cash? I helped you out where no one else could, and this is how you pay me back? You are a complete asshole to put me in this position!”

People were beginning to congregate outside my office to watch the meltdown. Neil Bogart walked in through our adjoining office door, clearly surprised at my outburst, and attempted to talk me off the ledge. No one had ever heard me yell with such venom and hatred. And they certainly had never heard me yell at Bill Wardlow.

Bill had promised me that our three-disc soundtrack LP for

Thank God It’s Friday

would be No. 1. Now he was reneging and giving the top slot to

Saturday Night Fever.

In truth,

Saturday Night Fever

deserved it. It was outselling us ten to one—easily—and I knew it. RSO, the label that had released

Saturday Night Fever,

shared a distributor with Casablanca, and I had access to their sales figures. The movie was doing much bigger box office than ours, too, but I didn’t care. Not only did I want to end

Saturday Night’

s impressive twenty-plus-week run at No. 1, but I also wanted the image enhancement that went along with being No. 1 and the increased sales for our picture and album.

Thank God It’s Friday

would be No. 1. Now he was reneging and giving the top slot to

Saturday Night Fever.

In truth,

Saturday Night Fever

deserved it. It was outselling us ten to one—easily—and I knew it. RSO, the label that had released

Saturday Night Fever,

shared a distributor with Casablanca, and I had access to their sales figures. The movie was doing much bigger box office than ours, too, but I didn’t care. Not only did I want to end

Saturday Night’

s impressive twenty-plus-week run at No. 1, but I also wanted the image enhancement that went along with being No. 1 and the increased sales for our picture and album.

For the past two years, I had had control over the

Billboard

charts and was able to significantly affect the positions of our records to help establish a perception that our company, Casablanca Records, and our artists—among them, KISS, Donna Summer, the Village People, and Parliament—were the hottest in the music industry. I was not going to accept a broken promise. This guy had screwed with the charts for years and years, and now he was screwing with me.

Billboard

charts and was able to significantly affect the positions of our records to help establish a perception that our company, Casablanca Records, and our artists—among them, KISS, Donna Summer, the Village People, and Parliament—were the hottest in the music industry. I was not going to accept a broken promise. This guy had screwed with the charts for years and years, and now he was screwing with me.

Casablanca was our child. We gave birth to it, we nurtured it, we fought many battles to keep it alive, and to have someone not give it the respect I felt it deserved was unacceptable. But this story begins long before I even knew who Bill Wardlow was, when Neil Bogart was not king of the hottest label in the record biz but just Neil Bogart, my second cousin from Brooklyn.

1

The Beginning of a Beautiful Friendship

The Beginning of a Beautiful Friendship

An Introduction: Neil and Bobby—Cameo-Parkway—

Art Kass and Buddah

Art Kass and Buddah

Summer 1961

5620 231st Street

Bayside, Queens

5620 231st Street

Bayside, Queens

The first time I met Neil Bogart—in fact, the first time I became aware he existed—we were in my parents’ living room in Bayside. Neil and his parents were introduced as relatives, but beyond that no explanation was given. They stayed for about five minutes and left me a copy of a single, titled “Bobby,” by some guy I’d never heard of named Neil Scott.

Turns out Neil Scott and Neil Bogart were the same person, and “Bobby” had been something of a hit, reaching No. 58 on the

Cashbox

and

Billboard

charts in June 1961. I had a relative who had recorded a song! I was fourteen years old and had never met anyone who had recorded a single, to say nothing of a hit—and to have him be a relative, no less, sent my head spinning.

Cashbox

and

Billboard

charts in June 1961. I had a relative who had recorded a song! I was fourteen years old and had never met anyone who had recorded a single, to say nothing of a hit—and to have him be a relative, no less, sent my head spinning.

As I would learn, Neil was a gambler—the kind of guy who would bet a hundred dollars on when the cheese in the fridge was going to go moldy—and he had wanted to be in entertainment for as long as he could remember. He was born Neil Bogatz in Brooklyn in 1943, and when he was young, his mother, Ruth, sent him for singing, dancing, and acting lessons (among his teachers was TV’s Archie Bunker, the late Carroll O’Connor). Family was always the center of the Bogatz’s world, and the generosity of spirit shared by Ruth and Neil’s father, Al, was apparent in every aspect of their lives. The family’s house doubled as a foster home, and at a very early age Neil acquired a larger sense of family that extended beyond bloodlines. It would shape his world, professionally and personally, throughout his life. Feeding and tending to such a large and ever-changing brood was expensive, and on Al’s postal service salary, the Bogatzes could scarcely afford luxuries like Neil’s acting lessons. As he always would, Neil persevered, and by the mid-1950s, he had become a performer at summer-stock-type camps in the Catskills; by nineteen, he was part of a song-and-dance team working Bermuda cruise ships. A year later, he was playing a club in New York City when Bill Darnell (a singer of some note in the 1940s and 1950s) saw him and said, “Your voice is bad enough to sound good on this song that we have.” That song was “Bobby.”

•

February 9, 1961: The Beatles give their debut performance, at the Cavern Club in Liverpool.

February 9, 1961: The Beatles give their debut performance, at the Cavern Club in Liverpool.

•

April 12, 1961: Yuri Gagarin, a Soviet cosmonaut, becomes the first human in space.

April 12, 1961: Yuri Gagarin, a Soviet cosmonaut, becomes the first human in space.

•

November 18, 1961: US president John F. Kennedy sends eighteen thousand military personnel to South Vietnam.

November 18, 1961: US president John F. Kennedy sends eighteen thousand military personnel to South Vietnam.

Neil was a born entrepreneur, and his promotional skills were often dazzling, even at a young age. When his single “Bobby” was pressed, he managed to get it played on the wildly popular Murray the K show on WINS-FM in New York. The radio show was hosted by Murray Kaufman, a pioneer in the radio business who more or less invented the concept of the fast-talking, high-energy DJ. On his show each day, two songs were paired in a competition. The one that received the most calls won. “Bobby” was pitted against an Elvis Presley tune—pretty tough competition. But Neil had one thing going for him that Presley didn’t. The afternoon of the contest, Neil organized a large group of old school friends to file into the candy store near PS 251 in Brooklyn. Using the store’s phone, Neil’s friends bombarded Murray the K with calls, eventually propelling “Bobby” to victory—this was likely the impetus that would push the song to hit status.

As are so many other skyrocket-to-stardom stories, Neil’s entrance into showbiz was due to a moment of blind luck and ballsy confidence. While working at an employment agency in Manhattan in 1965, he fielded a phone call from a representative of

Cashbox,

a powerful music industry magazine, who wanted to advertise a position in the magazine’s chart department. Rather than process the request and file the ad, Neil shelved it, went directly to

Cashbox’

s offices, and applied for the job himself. He secured the position and quickly worked his way up the company ladder, eventually landing a gig as assistant national promotion director with MGM Records, then one of the biggest labels in the industry. A year later, in early 1966, Neil parlayed his upward mobility into yet another choice gig when his former boss at

Cashbox

(who had since moved to Cameo-Parkway Records) offered him a job as national promotion director and eventually vice president and head of operations at Cameo. Neil thereby became the youngest person ever (at that point) to helm a major record label.

Cashbox,

a powerful music industry magazine, who wanted to advertise a position in the magazine’s chart department. Rather than process the request and file the ad, Neil shelved it, went directly to

Cashbox’

s offices, and applied for the job himself. He secured the position and quickly worked his way up the company ladder, eventually landing a gig as assistant national promotion director with MGM Records, then one of the biggest labels in the industry. A year later, in early 1966, Neil parlayed his upward mobility into yet another choice gig when his former boss at

Cashbox

(who had since moved to Cameo-Parkway Records) offered him a job as national promotion director and eventually vice president and head of operations at Cameo. Neil thereby became the youngest person ever (at that point) to helm a major record label.

One of Neil’s first accomplishments at Cameo was discovering and marketing the group ? & the Mysterians, who had a hit record with “96 Tears” in 1966. “That’s a very strange name for a song,” I thought. Neil later told me that the original title was “69 Tears,” a reference to the sexual position, but it was changed to make it marketable. Though, given Neil’s ability to sell a story, this may have been apocryphal.

In March 1967, early in Neil’s tenure as Cameo’s vice president, a controlling interest in the company was bought by Allen Klein (of Rolling Stones and Beatles fame). His view of what the label should be was at the opposite end of the universe from Neil’s, and it was clear that the relationship wasn’t long for this world. Fortunately for Neil, despite being a neophyte in an industry of emerging giants, his success was highly visible, and it left him with many opportunities. There was some speculation that Neil was pushed out of Cameo by Allen Klein, but that was not the case. Klein soon came under investigation and was eventually jailed when the company’s stock exploded overnight, attracting the attention of the SEC. Neil had seen the writing on the wall.

Not long after Klein bought Cameo-Parkway, Art Kass offered Neil a position as general manager of Kama Sutra Records and its newly formed sister label, Buddah. Timing is everything, especially in the go-for-broke music business, and with Cameo-Parkway’s future suddenly darkening, Neil jumped at Kass’s offer. Art was a former accountant at MGM Records (where he had first met Neil), and he had been brought in by Kama Sutra founders Hy Mizrahi, Artie Ripp, and Phil Steinberg to help establish the new company.

Kass had started Buddah in March 1967 as a way to get out of a distribution arrangement that existed between Kama Sutra and MGM, and he felt Neil was the perfect choice to help jump-start the new label. Kass, wisely, had the foresight to bring in Neil’s entire promotion staff (most notably, Marty Thau and Cecil Holmes) from Cameo-Parkway as well—why mess with a winning team? They did what they had done at Cameo: Marty handled the rock singles for radio, and Cecil promoted the R&B product. While Cecil would stay with Neil through the Casablanca days and be a major asset to the label, Marty would go on to become the original manager of the New York Dolls.

In contrast to the oppositional relationship he’d had with Allen Klein, Neil’s working relationship with Kass was amicable, and in the years to come it would bring great success to the company, spawning bubblegum music, a genre Neil once told me was about falling in love and sunshine—about enjoying pure entertainment and the good things in life.

Other books

The Five Elements by Scott Marlowe

Siege Of the Heart by Elise Cyr

Melabeth Forgive Me, For I Am Sin! by Hood, E. B.

Impulsive (Reach out to Me) by McGreggor, Christine

The Watcher by Jean, Rhiannon

Mr. Real (Code of Shadows #1) by Crane, Carolyn

Shadow of Ashland (Ashland, 1) by Terence M. Green

Their Fractured Light: A Starbound Novel by Amie Kaufman, Meagan Spooner

No-One Ever Has Sex on a Tuesday by Tracy Bloom

Student Body (Nightmare Hall) by Diane Hoh