And the Band Played On (17 page)

Read And the Band Played On Online

Authors: Christopher Ward

Although incorrectly listed by the

Mackay-Bennett

’s purser as ‘W. Hotley’, the mistake was quickly picked up and body number 224 was positively identified as that of Hartley on arrival in Halifax. His family in Colne, Lancashire, were informed by telegram the same day, 1 May, and at once asked for his body to be sent home.

Before the

Mackay-Bennett

’s arrival, White Star Line managers had been maintaining that ‘normal cargo rates would apply’ if anyone wanted a coffin shipped back to Europe. Whether or not Wallace’s family were made to pay we do not know but on the morning of Friday 17 May his coffin arrived in Liverpool on the White Star liner RMS

Arabic

, which also brought home the bodies of two other

Titanic

victims. Wallace’s father, Albion, met the liner with a horse-drawn hearse that had travelled the sixty miles from Colne the previous day. There were formalities to be completed before they made the return journey. First, Albion Hartley had the unpleasant task of identifying his son. The American-style coffin allowed part of the lid to be removed and for the face to be seen behind a glass panel; Albion then had to sign the receipt for his son’s effects. They included his epaulettes which someone on the

Mackay-Bennett

had thoughtfully removed from his bandsman’s uniform to include with his other possessions.

The return journey took ten hours, the hearse arriving in Colne in the middle of the night. Hartley’s coffin was taken straight to the Bethel Chapel where he had once been a chorister and his father a choirmaster. An inscribed brass plate had been engraved in advance and this was now affixed to the coffin. It said simply:

WALLACE H. HARTLEY

Died April 15th, 1912

Aged 33 years

‘Nearer My God To Thee’

All the next morning, mourners filed past the coffin. More than a thousand people came to the service, far more than the chapel could accommodate. But it was the extraordinary scenes afterwards, the outpouring of public grief, that revealed the emotion that the

Titanic

, and in particular the band, had aroused among the ordinary people of Britain. Thirty thousand people, more than the population of the town, lined the streets to pay their respects as the hearse carrying Hartley’s coffin made the journey from the chapel to the cemetery at the top of the hill. They came from all around: millworkers, miners, musicians. Four mounted police led the cortège, while thirty other policemen followed on foot. The Colne brass band was joined by several colliery bands from Yorkshire and Lancashire.

Reports and photographs of Hartley’s funeral dominated the newspapers for two days. Mary Costin passed the newspaper to her mother after she had finished reading it. ‘I know I ought to feel proud,’ she told her mother, ‘but all I feel is envy that the Hartleys have someone to bury.’ She didn’t even know that they had found Jock, let alone that he had been buried two weeks earlier.

12

Mary ‘Slurs’ a Dead Man

28 June, Buccleuch Street, Dumfries

The outpouring of grief that accompanied the sinking of the

Titanic

was immediately followed by the spontaneous desire of ordinary members of the public to help the widows and orphans of those who had died. Many families were facing real hardship, having lost husbands, fathers, sons or brothers. Southampton had provided 724 crew members, of whom only 175 returned home to their families.

On both sides of the Atlantic, people responded generously in their hour of need. In Britain, King George V set a sterling example by giving 5,000 guineas; church parish councils, Scout troops and ad hoc collection boxes multiplied this sum many times over as people gave as much as they could afford and more. At Castle Douglas near Dumfries, the Scout troop raised £47, a remarkable sum for boys to raise, equivalent to approximately £2,000 today.

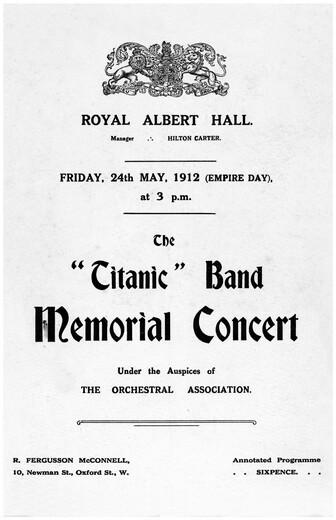

In May, a 500-strong orchestra staged the largest concert ever held at the Royal Albert Hall in aid of the families. Ten thousand people came to see Sir Henry Wood and Edward Elgar conduct an emotional programme. The

Daily Sketch

reported next day:

The supreme moment of the day came when Sir Henry Wood led the orchestra through the first eight bars of ‘Nearer My God To Thee’ and then, turning to the audience, he conducted the singing to the end. Ten thousand people, whose minds were filled with thoughts of one of the greatest sea tragedies ever known, sang the hymn with deep feeling.

The hymn drew a particularly emotional response from ‘two ladies sitting in a box near the royal party’ according to the

Sketch

. The last time they had heard ‘Nearer My God To Thee’ they had been in a lifeboat while the band played the hymn on the deck of the

Titanic

.

Several official funds were established in the aftermath of the tragedy to ensure that donations were distributed fairly and evenly, the largest being the Lord Mayor of London’s fund and the

Daily Telegraph Titanic

fund. Other collection centres were set up in Southampton, Glasgow and Liverpool. In time, these were amalgamated into a single fund called the

Titanic

Relief Fund.

By the end of June, the

Titanic

Relief Fund had raised £307,000 – the equivalent of £15 million today – and was sufficiently well organised to place advertisements in national and local newspapers inviting applications for grants from the dependants of those who had died. Mary Costin wrote to the fund on Friday 28 June, formally lodging an application for a grant, explaining that she was the fiancée of Jock Law Hume, violinist in the

Titanic

’s band, and was expecting his child in October. She did so on the advice of Mr Hendrie, a solicitor in the legal office where her mother Susan worked as a cleaner and caretaker. After Jock’s death in April, Hendrie had told Mary and her mother that he would help in any way he could and that there would be no question of fees. He was pleased to be of assistance.

Since Jock’s death, Mary had been overwhelmed by the kindness she had been shown at home and at work. Jock was popular and well known in Dumfries and people had expressed their grief at his loss by going out of their way to help her. Far from being embarrassed by her situation – by the end of June it was quite clear that she was expecting a baby – they seemed genuinely pleased for her. Her mother Susan had made things so much easier with their neighbours by talking at every opportunity about the new grandchild who was on the way, referring to the baby always as ‘Jock and Mary’s’. No one was left in any doubt that mother and daughter stood side by side in Mary’s adversity.

But behind the brave face she put on for the world, Mary was sad, lonely and worried. She was used to Jock not being there – as long as she had known him he had been away at sea for weeks or months at a time – but she found it difficult to come to terms with the idea that he was never coming back. She missed her brother, William, more than ever. And she was worried about money. In October she would have to take time off work to have the baby, with no guarantee that her job at the mill would be waiting for her when she came back.

The

Titanic

Relief Fund’s reply to Mary’s application came two weeks later, much sooner than she had hoped. But she was not pleased by what she read. The fund would be willing to regard her claim sympathetically, but ‘not at the cost of casting a slur on the family of the deceased man’. She should reapply after the birth of the child, providing ‘evidence of paternity’. By the time Mary showed the letter to Mr Hendrie in his office, she was in tears. Mr Hendrie was not at all surprised by the fund’s reply and tried to reassure her. ‘This is just procedure. They are legally obliged to be cautious. After the baby is born we will apply to the court for a paternity order. It is not normally a straightforward process, but in your situation it will be. There is nothing to worry about, I promise you.’ Mary was much comforted by what Mr Hendrie told her.

But there was nothing straightforward at all about the fund’s response. What neither of them knew was that Andrew Hume himself had also written to the

Titanic

Relief Fund lodging an appeal for a grant as a ‘dependant’ of the late Jock Law Hume. He added that he had ‘conclusive proof’ that his son was not the father of the child carried by a Miss Mary Costin of 35 Buccleuch Street, Dumfries.

13

Andrew Hume

A Fantasy World

All his life, Andrew Hume had been quick to exploit an opportunity and the death of his son Jock would be no exception. He saw the

Titanic

Relief Fund as a welcome windfall, which he had no intention of sharing with Mary or her bastard child. The Fund could make a significant difference to his lifestyle and he was quick to apply for whatever it had to offer while looking around for other low-hanging fruit. And there was plenty of that.

Within weeks of the tragedy, through the Amalgamated Musicians Union of which he was a member, Andrew Hume became aware of various fundraising initiatives in Britain and in the United States to raise money specifically for the families of the musicians who had died. Everyone who went down on the

Titanic

died a hero, but the eight musicians had achieved superhero status by playing on until the ship went down. Musicians who, like actors, have always been good at looking after their own, staged a series of emotional memorial concerts in Britain and in the United States. In New York and Boston these events were energetically promoted and generously supported by some of the wealthy Americans who survived the

Titanic

, all of whom had paid tribute to the band’s role in maintaining calm in the hour before the ship went down. Many were experienced and influential fundraisers, including Madeleine Astor, who helped organise a concert given by 500 musicians at the Moulin Rouge on Broadway in aid of the

Titanic

band. Her guest of honour at a fundraising lunch for big hitters was Captain Rostron, the captain of the

Carpathia

who had taken the

Titanic

survivors to New York.

None of these socialites knew about the existence of Mary, or that Jock had left behind an unborn child. Consequently, Jock’s father, being a musician himself, seemed a natural and deserving recipient of the fundraisers’ generosity. Unknown to Mary and most other people, including his family, Andrew Hume would bank more than £250 in handouts from charities over the coming months. He also developed a plan that would more than double the money he would receive in compensation for Jock’s death.

By 1912, Andrew Hume had established a growing reputation in the music industry throughout Britain as an accomplished all-round musician. He was as proficient with the banjo and guitar as he was with the piano and the violin, as comfortable playing ragtime as Rachmaninov. He performed regularly in concerts and had led an orchestra of forty at the newly opened West End Pier in Morecambe, Lancashire, during its opening summer season, spending ten weeks away from home. He taught music, giving private lessons at home as well as taking classes at local schools and academies. He was a conductor, seen with his baton on the bandstand in Dumfries’s Dock Park most Sunday afternoons. And he also made violins.