Andre Dubus: Selected Stories (63 page)

‘I’m all right.’

‘What happened?’

‘I don’t know. I fainted.’

I got out and went around to the front of the car, looked at the smashed light, the crumpled and torn fender.

‘Come to the house and lie down.’

‘I’m all right.’

‘When was your last physical?’

‘I’m due for one. Let’s get out of this rain.’

‘You’d better lie down.’

‘No. I want to receive.’

That was the time to say I want to confess, but I have not and will not. Though I could now, for Jennifer is in Florida, and weeks have passed, and perhaps now Father Paul would not feel that he must tell me to go to the police. And, for that very reason, to confess now would be unfair. It is a world of secrets, and now I have one from my best, in truth my only, friend. I have one from Jennifer too, but that is the nature of fatherhood.

Most of that day it rained, so it was only in early evening, when the sky cleared, with a setting sun, that two little boys, leaving their confinement for some play before dinner, found him. Jennifer and I got that on the local news, which we listened to every hour, meeting at the radio, standing with cigarettes, until the one at eight o’clock; when she stopped crying, we went out and walked on the wet grass, around the pasture, the last of sunlight still in the air and trees. His name was Patrick Mitchell, he was nineteen years old, was employed by CETA, lived at home with his parents and brother and sister. The paper next day said he had been at a friend’s house and was walking home, and I thought of that light I had seen, then knew it was not for him; he lived on one of the streets behind the club. The paper did not say then, or in the next few days, anything to make Jennifer think he was alive while she was with me in the kitchen. Nor do I know if we—I—could have saved him.

In keeping her secret from her friends, Jennifer had to perform so often, as I did with Father Paul and at the stables, that I believe the acting, which took more of her than our daylight trail rides and our night walks in the pasture, was her healing. Her friends teased me about wrecking her car. When I carried her luggage out to the car on that last morning, we spoke only of the weather for her trip—the day was clear, with a dry cool breeze—and hugged and kissed, and I stood watching as she started the car and turned it around. But then she shifted to neutral and put on the parking brake and unclasped the belt, looking at me all the while, then she was coming to me, as she had that night in the kitchen, and I opened my arms.

I have said I talk with God in the mornings, as I start my day, and sometimes as I sit with coffee, looking at the birds, and the woods. Of course He has never spoken to me, but that is not something I require. Nor does He need to. I know Him, as I know the part of myself that knows Him, that felt Him watching from the wind and the night as I kneeled over the dying boy. Lately I have taken to arguing with Him, as I can’t with Father Paul, who, when he hears my monthly confession, has not heard and will not hear anything of failure to do all that one can to save an anonymous life, of injustice to a family in their grief, of deepening their pain at the chance and mystery of death by giving them nothing—no one—to hate. With Father Paul I feel lonely about this, but not with God. When I received the Eucharist while Jennifer’s car sat twice-damaged, so redeemed, in the rain, I felt neither loneliness nor shame, but as though He were watching me, even from my tongue, intestines, blood, as I have watched my sons at times in their young lives when I was able to judge but without anger, and so keep silent while they, in the agony of their youth, decided how they must act; or found reasons, after their actions, for what they had done. Their reasons were never as good or as bad as their actions, but they needed to find them, to believe they were living by them, instead of the awful solitude of the heart.

I do not feel the peace I once did: not with God, nor the earth, or anyone on it. I have begun to prefer this state, to remember with fondness the other one as a period of peace I neither earned nor deserved. Now in the mornings while I watch purple finches driving larger titmice from the feeder, I say to Him: I would do it again. For when she knocked on my door, then called me, she woke what had flowed dormant in my blood since her birth, so that what rose from the bed was not a stable owner or a Catholic or any other Luke Ripley I had lived with for a long time, but the father of a girl.

And He says: I am a Father too.

Yes, I say, as You are a Son Whom this morning I will receive; unless You kill me on the way to church, then I trust You will receive me. And as a Son You made Your plea.

Yes, He says, but I would not lift the cup.

True, and I don’t want You to lift it from me either. And if one of my sons had come to me that night, I would have phoned the police and told them to meet us with an ambulance at the top of the hill.

Why? Do you love them less?

I tell Him no, it is not that I love them less, but that I could bear the pain of watching and knowing my sons’ pain, could bear it with pride as they took the whip and nails. But You never had a daughter and, if You had, You could not have borne her passion.

So, He says, you love her more than you love Me.

I love her more than I love truth.

Then you love in weakness, He says.

As You love me, I say, and I go with an apple or carrot out to the barn.

Andre Dubus (1936–1999) is considered one of the greatest American short story writers of the twentieth century. His collections of short fiction, which include

Adultery & Other Choices

(1977),

The Times Are Never So Bad

(1983) and

The Last Worthless Evening

(1986), are notable for their spare prose and illuminative, albeit subtle, insights into the human heart. He is often compared to Anton Chekhov and revered as a “writer’s writer.”

Born on August 11, 1936, in Lake Charles, Louisiana, Dubus grew up the oldest child of a Cajun-Irish Catholic family in Lafayette. There, he attended the De La Salle Christian Brothers, a Catholic school that helped nurture a young Dubus’s love of literature. He later enrolled at McNeese State College in Lake Charles, where he acquired his BA in English and journalism. Following his graduation in 1958, he spent six years in the United States Marine Corps as a lieutenant and captain—an experience that would inspire him to write his first and only novel,

The Lieutenant

(1967). During this time, he also married his first wife, Patricia, and started a family.

After concluding his military service in 1964, Dubus moved with his wife and their four children to Iowa City, where he was to earn his MFA from the prestigious Iowa Writers’ Workshop at the University of Iowa. While there, he studied under acclaimed novelist and short story writer Richard Yates, whose particular brand of realism would inform Dubus’s work in the years to come. In 1966, Dubus relocated to New England, teaching English and creative writing at Bradford College in Bradford, Massachusetts, and beginning his own career as an author. Over an illustrious career, he wrote a total of six collections of short fiction, two collections of essays, one novel, and a stand-alone novella,

Voices from the Moon

(1984)—about a young boy who must come to terms with his faith in the wake of two family divorces—and was awarded the

Boston Globe

’s first annual Lawrence L. Winship Award, the PEN/Malamud Award, the Rea Award for the Short Story, and the Jean Stein Award from the American Academy of Arts and Letters, as well as fellowships from the Guggenheim and MacArthur Foundations.

In the summer of 1986, tragedy struck when Dubus pulled over to help two disabled motorists on a highway between Boston and his home in Haverhill, Massachusetts. As he exited his car, another vehicle swerved and hit him. The accident crushed both his legs and would confine him to a wheelchair for the rest of his life. Plagued by residual pain, he sunk into a depression that was further exacerbated by his divorce from his third wife, Peggy, and subsequent estrangement from their two young daughters, Cadence and Madeleine. Buoyed by his faith, he continued to write—in his final decade, he would pen two books of autobiographical essays,

Broken Vessels

(1991) and

Meditations from a Moveable Chair

(1998), and a final collection of short stories,

Dancing After Hours

(1996), which was a National Book Critics Circle Award finalist—and even held a workshop for young writers at his home each week.

In 1999, Dubus died of a heart attack at the age of sixty-two. He is survived by three ex-wives and his six children, among them the author Andre Dubus III. Since his death, two of Dubus’s short works have been adapted for the screen: “Killings,” which was featured in

Finding a Girl in America

(1980), became the critically acclaimed film

In the Bedroom

(2001), starring Sissy Spacek, Tom Wilkinson, and Marisa Tomei; and

We Don’t Live Here Anymore

(2004), starring Mark Ruffalo, Laura Dern, Peter Krause, and Naomi Watts, is based on Dubus’s novella of the same name from his debut collection,

Separate Flights

(1975).

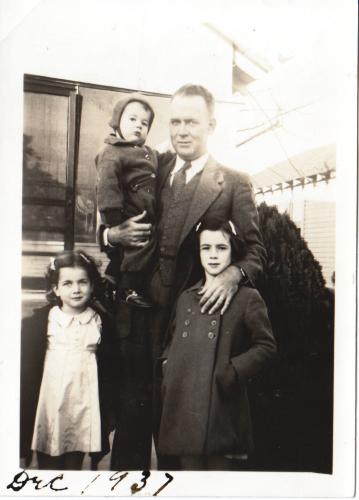

Dubus Sr., with a sixteen-month-old Andre in Lake Charles, Louisiana. Andre’s sister Elizabeth is on the left and Kathryn is on the right. The family is bundled up for the Louisiana winter, which Kathryn remembers as being much colder during her childhood than it is now.

Dubus with classmates from his first- or second-grade class, around 1940. Dubus is second from the left, displaying what his father called his “ethereal face.”

The Dubus family in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, around 1941. Andre Jr., stands in front, while his father, Andre Sr.; mother, Katherine; and sisters, Elizabeth and Kathryn, from left to right, stand in the back.

Dubus’s freshman or sophomore school photo from Cathedral High School, around 1951. Dubus gave this photo to his recently married sister with a note on the back saying, jokingly, “To a good cook from the only one polite enough to eat her meals.”

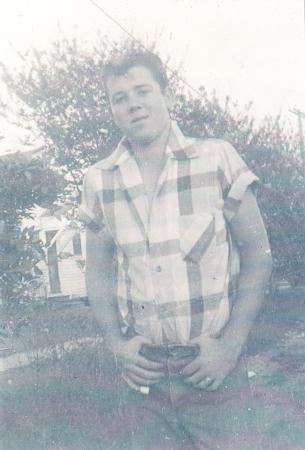

A fifteen-year-old Dubus, seen here in 1952.

Dubus as a young Marine in Quantico, Virginia, where he received his training and became a commissioned officer in 1957.

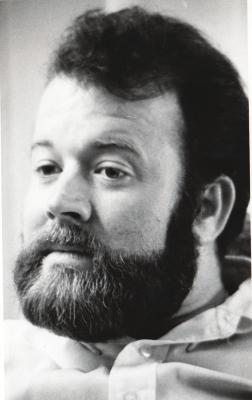

Dubus around 1967, while he was working at Bradford College in Bradford, Massachusetts. This photo was taken by one of his students.

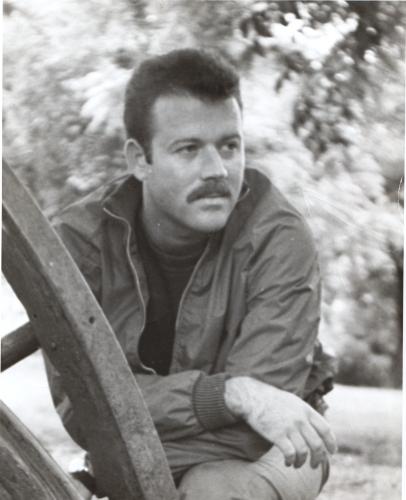

A photo of Dubus taken by a fellow student at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop in Iowa City, around 1965. This photo was used as a dust jacket picture as well as in a newspaper story from Dubus’s hometown announcing the publication of his first novel,

The Lieutenant

(1967).