Anne Morrow Lindbergh: Her Life (10 page)

Read Anne Morrow Lindbergh: Her Life Online

Authors: Susan Hertog

Their shadow seemed like a “great bird”

18

soaring above the lakes and meadows. Suddenly, Anne understood: she was inside the bird and part of its shadow. The city below looked like a child’s toy; everything her parents knew as grand and imposing now seemed small and insignificant. Only the mountains retained their majesty, and even they seemed to bow in awe.

Flying with Lindbergh as he cut through the sky, Anne understood why he feared nothing. She felt as if, like him, “life had found her—and death, too.”

19

Later that night, she wrote in her diary: “The idea of this clear, direct, straight boy—how it has swept out of sight all other men I have ever known … my little embroidery beribboned world is smashed.”

20

The Early Years

D

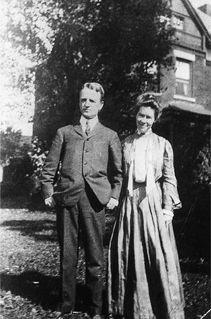

wight and Elizabeth Morrow, home from their honeymoon. Englewood, New Jersey, 1903

.

(Amherst College Archives)

AMILY

A

LBUM

1

My parents, my children:

Who are you, standing there

In an old photograph—young married pair

I never saw before, yet see again?

You pose somewhat sedately side by side

,

In your small yard off the suburban road

.

He stretches a little in young manhood’s pride

Broadening his shoulders for the longed-for load

,

The wife that he has won, a home his own;

His growing powers hidden as spring, unknown

,

But surging in him toward their certain birth

,

Explosive as dandelions in the earth

.She leans upon his arm, as if to hide

A strength perhaps too forward for a bride,

Feminine in her bustle and long skirt;

She looks demure, with just a touch of flirt

In archly tilted head and squinting smile

At the photographer, she watches while

Pretending to be girl, although so strong,

Playing the role of wife (“Here I belong!”),

Anticipating mother, with man for child,

Amused at all her roles, unreconciled

.And I who gaze at you and recognize

The budding gestures that were soon to be

My cradle and my home, my trees, my skies

…—ANNE MORROW LINDBERGH

PRING

1893, N

ORTHAMPTON

, M

ASSACHUSETTS

B

etty Cutter was in an awful temper the day she met Dwight Morrow at a school dance. Local dances had a clandestine air, and Betty liked to play by the rules. Her friends who waited at the Northampton station for the boys from Amherst to arrive were a bit too eager for Betty’s taste, risking their Smith College “dignity” in a frivolous breach of self-restraint. Smith parties, held inside the college gates, perfectly suited Betty’s sensibilities. Church-like socials, more like conversations set to music, they were tightly monitored by faculty chaperones, and Betty could be back in her room by ten. But this was an informal dance, held at the local girls’ school and although it was slated for midmorning, it had live music, “round” dancing, and lax rules. Ungoverned by the rituals of dance cards and numbers, the girls enjoyed the chaos in the gym as, nearly tripping on their long dresses, they raced to find partners for the first dance. The beautiful girls got their pick; the others trailed, fearing they would be left behind. Betty, plain-faced and delicate, with a pug nose and a slight build, lingered at the edge of the dance floor in a defiant pose. But Dwight, eager for the challenge, was thoroughly “beguiled.” To Betty’s surprise, they danced all day.

2

Nearly twenty years old, and well into her sophomore year, Betty had to face reality. Graduation was only two years away, and she dreaded the thought of going home. Home meant submitting to the tight restrictions of her parents and carrying out part-time care of her younger sisters, one of whom was severely retarded.

3

Marriage, against Betty’s deepest instincts for independence and a literary career, was a distasteful yet sensible alternative. And the determined Mr. Morrow, as tenacious and as ambitious as she, was, for the moment, a pleasant companion.

As they waltzed around the school gym that spring morning of 1893 at their first meeting, Betty could only have felt the harmony of their views. Like the Morrows, the Cutters were educated and pious, affected by the same turn-of-the-century mix of Puritan energy and the drive for upward mobility. The Morrow ancestors had been farmers in

the highlands of Ireland, immigrating to America in the early 1700s; the Cutters had arrived nearly a century before from the mining towns of northeastern England, where they earned their living as glaziers, shoemakers, millers, blacksmiths, and coopers. In America they stayed one step behind the frontier settlers, who required their services to sustain their communities. Urban dwellers, the Cutters settled first in Boston and then moved to New Hampshire, Vermont, Pennsylvania, and Ohio. There they became teachers, doctors, lawyers, and merchants, rising quickly through the social strata.

4

The Cutter scion to whom Betty and her twin sister, Mary, were born on May 29, 1873, had deserted the farmlands of Vermont to follow the inland seaways and lakes to the port town of Cleveland, Ohio. While her grandfather had been an uneducated farmer who made his money in the marketplace, her step-grandfather was a blue-blooded Yankee, educated at Yale and ambitious for his stepsons. Her father, Charles, temperamentally unsuited to his legal profession or any other formal vocation, was a sensitive and gentle man who loved his books, his garden, and the comforts of home. Frustrated by his inability to earn a living, he soon grew tired, weak, and depressed, and sought refuge with his wife and four daughters in his parents’ sprawling three-generation home.

Like Dwight’s mother, Clara, Betty’s mother, Annie Spencer, would always feel that her husband had failed her. And like Dwight, Betty believed herself responsible for her mother’s domestic burdens and economic disappointments. Nonetheless, the Cutters, like the Morrows, drew strength from their religion. Annie Cutter, a descendent of a “long line of roaring fundamentalist Congregationalist preachers,” made the Bible, with its parables and its ethics, the fulcrum of her children’s daily lives. And Betty, using the Hebrew Bible and the New Testament as her primers, cultivated a love of stories and poetry.

At the age of ten, after a long bout of tuberculosis, Betty’s twin sister died. The family eulogized Mary as God’s “little angel,” and Betty, uncertain of the purity of her own soul, struggled to find her place alone.

5

Hiding beneath the front hall stairs from her grandparents, her

parents, and her sisters, Betty read books and wrote in her diary. While visits to her wealthy cousins, the Dillinghams, would teach Betty the privileges and pleasures of the rich, she also saw the emotional poverty of women whose pleasure in life was defined by their husbands’ wealth and status. Books, she believed, would be her “ticket out.” Independence required a college education.

After persuading her parents to let her attend a girls’ preparatory school, Betty got “the wish of her life.” In the fall of 1892, she boarded the train to Northampton, Massachusetts, en route to Smith College, with two new dresses, made by her mother, a desk donated by her Uncle Arthur, and a painting by her Aunt Mary intended to lend “homeliness” to her college room. The 108 students in Betty’s freshman class were among the 2.8 percent of women who went to college in the 1890s.

6

Even those who could afford the “Eastern elites” often tutored their daughters at home. While the parents of most college women had incomes twice as high as the national average, the Cutters felt the financial burden. If it hadn’t been for Uncle Arthur, who had nurtured her after her twin’s death and who understood her need for autonomy, Betty would have remained at home.

But back in Cleveland after graduation, in the summer of 1896, Betty realized that her “ticket out” had been nothing more than a round-trip ticket home. Caught, once again, in the quagmire of her family’s needs, Betty understood, perhaps for the first time, the depth of her mother’s sadness. Annie Cutter was exhausted and depressed, as much from the effort of hiding the family’s poverty beneath genteel postures as she was from the poverty itself. Her unhappiness elicited Betty’s sympathy, along with her guilt. It was an old guilt, perhaps, based on Betty’s desire to fill the emotional vacuum made by her twin’s death.

Betty wrote in her diary, “My blessed mother, she shall have happiness from now on if I can give it to her.” Betty wanted to make her mother happy by staying at home and helping her to care for the children, but her own ambition—her desire to write—constantly cracked through to the surface. “I must accomplish something, I must do something,

I must be something.” By September, only three months out of college, Betty understood that autonomy would require money. “Oh if only I were a boy,” she wrote in her diary, “how gladly would I go to work.”

7

Although her success at Smith had convinced her that she could find a career in writing, within a year after graduation Betty’s hopes were dashed, so in the fall of 1896, she devised a new plan for making money. If she could not publish fiction, she would teach it. Betty secured the elegant front room in the house of a well-off cousin and tried her hand at “parlor-teaching.” Although in one semester she earned the astonishing sum of $574, she came to “despise” the work. She doubted both the quality of her skills and the worth of her students. In a sense, she had become a caricature of herself, preaching the insights of Ibsen’s

Doll’s House

to a group of middle-aged “ladies” from town.

Betty was frustrated that she had achieved nothing, while Dwight was “marching straight ahead with no worries.” She was beginning to believe that her task was impossible: to be “historical and social and domestic all at once.” Although her confinement at home made her “mean and little and tired of spirit,” she had not lost her love of parties and travel.

8

By the spring of 1897 she was through with parlor talks, and the possibility of marrying Dwight Morrow resurfaced with new meaning. Yet moving away from home seemed out of the question; how could she leave her mother behind? “My dear mother, how can I ever go away?”

Dwight, who had entered Amherst College on academic probation, had graduated in 1895 as class orator, had been elected to Phi Beta Kappa, and was noted as one of those most likely to succeed. Then, after a year back home in Pittsburgh, working as an office boy for his cousin Richard Scandrett, he went to New York and enrolled in Columbia University’s School of Law, where his tuition was covered by his father and a part-time job. At Columbia he met the sons of lawyers and businessmen, who introduced him to the life of the New York rich, with their townhouses and Long Island estates. Dwight may have been

ashamed of his shabby clothes and unpolished manner, but he won his new friends’ admiration with his mind and his morals. He did protest that his “rich” friends heightened the value of his “poor friends,” but he was hungrier and more ambitious than ever before. And Betty Cutter, with her aspirations for a “Madison Avenue” life, seemed within Dwight’s reach.

9

Hoping to impress her with his “grand move,” he wrote to Betty in Cleveland to tell her the news. She clearly admired his courage and his success; still, one can sense her painful recognition that her own career as a writer was doomed.