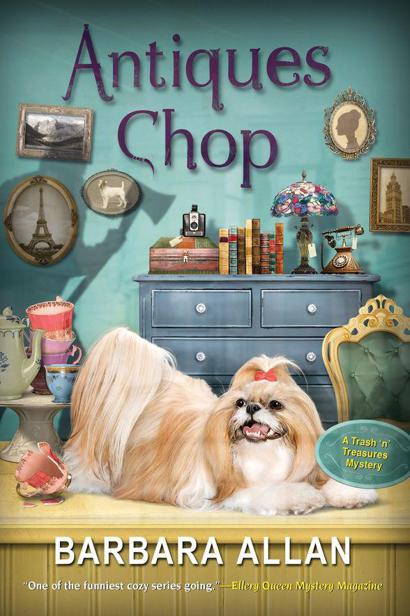

Antiques Chop (A Trash 'n' Treasures Mystery)

Read Antiques Chop (A Trash 'n' Treasures Mystery) Online

Authors: Barbara Allan

BOOK: Antiques Chop (A Trash 'n' Treasures Mystery)

13.03Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

Also by Barbara Allan:

ANTIQUES ROADKILL

ANTIQUES MAUL

ANTIQUES FLEE MARKET

ANTIQUES BIZARRE

ANTIQUES KNOCK-OFF

ANTIQUES DISPOSAL

By Barbara Collins:

TOO MANY TOMCATS (short story collection)

By Barbara and Max Allan Collins:

REGENERATION

BOMBSHELL

MURDER—HIS AND HERS (short story collection)

Antiques Chop

A Trash ‘n’ Treasures Mystery

Barbara Allan

KENSINGTON BOOKS

http://www.kensingtonbooks.com

http://www.kensingtonbooks.com

All copyrighted material within is Attributor Protected.

Table of Contents

Also by Barbara Allan:

Title Page

Dedication

Cast Of Characters

Chapter One - Chop Meet

Chapter Two - Chop Talk

Chapter Three - Chopped Liver

Chapter Four - Chop Till You Drop

Chapter Five - Choppy Waters

Chapter Six - Chop Around

Chapter Seven - Chop Chop

Chapter Eight - Stop and Chop

Chapter Nine - Chop Lifting

Chapter Ten - Chop Class

Chapter Eleven - Window Chopping

Chapter Twelve - Chopping Block

Copyright Page

Title Page

Dedication

Cast Of Characters

Chapter One - Chop Meet

Chapter Two - Chop Talk

Chapter Three - Chopped Liver

Chapter Four - Chop Till You Drop

Chapter Five - Choppy Waters

Chapter Six - Chop Around

Chapter Seven - Chop Chop

Chapter Eight - Stop and Chop

Chapter Nine - Chop Lifting

Chapter Ten - Chop Class

Chapter Eleven - Window Chopping

Chapter Twelve - Chopping Block

Copyright Page

In memory of Martin H. Greenberg,

who gave Barbara her start

who gave Barbara her start

Brandy’s quote:

“No one ever keeps a secret

so well as a child

.”

Jean de La Fontaine

“No one ever keeps a secret

so well as a child

.”

Jean de La Fontaine

Mother’s quote:

“Be who you are and say what you feel

because those who mind don’t matter

and those who matter don’t mind.

”

Dr. Seuss

“Be who you are and say what you feel

because those who mind don’t matter

and those who matter don’t mind.

”

Dr. Seuss

Cast Of Characters

Note from Brandy:

Mother has been begging me to open one of our books with a cast of characters—no doubt this reflects her theatrical background, but also she recalls reading Agatha Christie, Erle Stanley Gardner, and other Golden Age mystery writers, and relishing this “helpful aid” in keeping track of who’s who. I am giving in to her, just this once, because (A) it will help catch new readers up, (B) refresh readers who’ve been following our exploits, and (C) shut Mother up (temporarily). This cast list pertains only to recurring characters—you’ll have to keep track of the new ones on your own.

Mother has been begging me to open one of our books with a cast of characters—no doubt this reflects her theatrical background, but also she recalls reading Agatha Christie, Erle Stanley Gardner, and other Golden Age mystery writers, and relishing this “helpful aid” in keeping track of who’s who. I am giving in to her, just this once, because (A) it will help catch new readers up, (B) refresh readers who’ve been following our exploits, and (C) shut Mother up (temporarily). This cast list pertains only to recurring characters—you’ll have to keep track of the new ones on your own.

Brandy Borne,

thirty-one, bottle-blonde Prozac-popping divorcee who came running home to live with Mother in small-town Serenity, Iowa.

thirty-one, bottle-blonde Prozac-popping divorcee who came running home to live with Mother in small-town Serenity, Iowa.

Vivian Borne

(a.k.a. Mother)

,

widow, seventyish, bipolar, part-time community theater actress and antiques hound, full-time sleuth.

(a.k.a. Mother)

,

widow, seventyish, bipolar, part-time community theater actress and antiques hound, full-time sleuth.

Sushi,

blind, diabetic shih tzu.

blind, diabetic shih tzu.

Jake,

Brandy’s thirteen-year-old son who lives with ex-husband Roger in Chicago.

Brandy’s thirteen-year-old son who lives with ex-husband Roger in Chicago.

Roger,

ex-husband, forties, investment broker.

ex-husband, forties, investment broker.

Peggy Sue,

early fifties, recently widowed and Brandy’s sister. Also Brandy’s recently revealed biological mother.

early fifties, recently widowed and Brandy’s sister. Also Brandy’s recently revealed biological mother.

Ashley,

twenty, Peggy Sue’s daughter attending college out east.

twenty, Peggy Sue’s daughter attending college out east.

Senator Edward Clark,

sixty, Brandy’s recently revealed biological father.

sixty, Brandy’s recently revealed biological father.

Brian Lawson,

early thirties, chief of police and Brandy’s current flame.

early thirties, chief of police and Brandy’s current flame.

Tony Cassato,

late forties, former chief of police and Brandy’s former flame. Currently in WITSEC (Witness Protection Program).

late forties, former chief of police and Brandy’s former flame. Currently in WITSEC (Witness Protection Program).

Rocky,

Tony’s black-and-white mixed breed dog with a K.O. circle around one eye; currently living with Brandy and Mother.

Tony’s black-and-white mixed breed dog with a K.O. circle around one eye; currently living with Brandy and Mother.

Back to Brandy:

Got all that? Yeah, me neither....

Got all that? Yeah, me neither....

From

The Encyclopedia of Heartland Murders

(Kensington, 1995), Patrick Culhane. Used by permission.

The Encyclopedia of Heartland Murders

(Kensington, 1995), Patrick Culhane. Used by permission.

Archibald Butterworth

(1908–1950) was the victim in an ax murder that the

Des Moines Register

called “a modern-day Lizzie Borden mystery.” Butterworth was a distinguished if little-liked member of the small river community, Serenity, Iowa. But there was nothing serene about the circumstances of his death on the hot, muggy afternoon of Sunday, August 27, 1950.

(1908–1950) was the victim in an ax murder that the

Des Moines Register

called “a modern-day Lizzie Borden mystery.” Butterworth was a distinguished if little-liked member of the small river community, Serenity, Iowa. But there was nothing serene about the circumstances of his death on the hot, muggy afternoon of Sunday, August 27, 1950.

Butterworth was a failed Republican candidate for state senate, a longtime city council member, and a staunch member of the Amazing Grace Baptist Church. He was said to have prided himself on his piety, sobriety, and frugality. Others apparently considered him a hypocritical latter-day Scrooge. Left a small inheritance by his farmer father, Butterworth spent the Depression years shrewdly (or perhaps heartlessly) buying up foreclosed homes on the northwest edge of town. During the post–WW2 housing shortage, many veterans returning to Serenity became Butterworth’s tenants. Pious or not, Butterworth was considered by many a notorious slumlord.

Apparently no more generous to himself than his North Side tenants, Butterworth lived modestly, his home—on the edge of Serenity’s downtown, at the bottom of West Hill, which rose to the mansions of other wealthy residents—a small, two-story clapboard with insufficient heating in winter and no air-conditioning in summer. Butterworth was rumored to live lavishly while on his frequent travels, while maintaining an austerely frugal front at home.

Butterworth’s wife, Amelia, died in 1936, giving birth to the couple’s only son, Andrew; a sister, Sarah, had been born in 1935. Young Andy excelled in sports and the arts and achieved a local popularity denied his father. After church on the sweltering morning of Sunday, August 27, 1950, the fourteen-year-old was heard arguing with his father in the church parking lot over money—apparently a simple matter of the boy wanting either an allowance or permission to work after school.

That afternoon, with daughter Sarah away for the weekend, Archibald Butterworth napped on his couch in his study at home. Midafternoon, someone entered with an ax and delivered half a dozen savage blows that killed the town miser in his sleep.

While not matching the mythical “forty whacks” of the

Borden

case, those half-dozen blows were enough to put sleepy Serenity on the map. The sole suspect in a case drawing national attention was son Andrew, who claimed to have spent the afternoon fishing, by himself, at a local pond. He had been noticed by neighbors early that afternoon, however, chopping wood furiously in the Butterworth backyard. But after the murder, that ax, usually seen deposited in a tree stump by the family woodpile, was nowhere to be found.

Borden

case, those half-dozen blows were enough to put sleepy Serenity on the map. The sole suspect in a case drawing national attention was son Andrew, who claimed to have spent the afternoon fishing, by himself, at a local pond. He had been noticed by neighbors early that afternoon, however, chopping wood furiously in the Butterworth backyard. But after the murder, that ax, usually seen deposited in a tree stump by the family woodpile, was nowhere to be found.

In addition to the well-known animosity between father and son, a major clue was that missing wood-chopping implement. Whether this was indeed the murder weapon remains unknown.

The youth was held for questioning. A young attorney, Wayne Ekhardt, came forward to represent Andrew, producing a witness who could confirm the Butterworth boy had indeed been fishing. Thanks to the sworn statement of a lovely little twelve-year-old girl—who lived in the neighborhood—no charges were ever proferred against Andrew.

Or anyone else. Police looked into rumors of an affair between Archibald and a married woman, but got nowhere. The idea of the tall, bearded, foreboding Butterworth as a Lothario seemed far-fetched to locals, and as the years passed, the notion that Andrew may actually have killed his father took hold in the small town. After all, the young girl who had cleared him was an impressionable child, prone to theatrics, it was said. Had indeed little Vivian Jensen been an accomplice of sorts to the crime?

Interviewed in later years, Vivian Jensen Borne—now known locally as the town’s resident theatrical diva—denied any such complicity. Andrew rehabilitated his own reputation (if not his father’s) by selling the rental properties at a loss to any interested tenants, and remodeling the rest of the properties.

While to this day he maintains a residence in Serenity—in one of the mansions on the hill his father could have lived in, but chose not to—Andrew Butterworth has for many years lived primarily overseas. He has never married, and travels frequently, the latter perhaps the only thing he had in common with his late, murdered father.

Attorney Wayne Ekhardt, whose first well-publicized victory was won without stepping inside a courtroom, went on to fame as Iowa’s most celebrated criminal attorney (see separate entries,

Ekhardt, Wayne

, and

Woman Who Shot Her Husband in the Back in Self-Defense, The

).

Ekhardt, Wayne

, and

Woman Who Shot Her Husband in the Back in Self-Defense, The

).

Chapter One

Chop Meet

Previously, in

Antiques Knock-off

. . .

Antiques Knock-off

. . .

I

don’t remember walking from the backyard, where I’d been working, to the front porch, to sit in the old rocker . . . but I must have, because half an hour later I was still there, rocking listlessly, letting the cool fall breeze rustle my shoulder-length bleached-blond hair, when a huge silver Hummer pulled into the drive.

don’t remember walking from the backyard, where I’d been working, to the front porch, to sit in the old rocker . . . but I must have, because half an hour later I was still there, rocking listlessly, letting the cool fall breeze rustle my shoulder-length bleached-blond hair, when a huge silver Hummer pulled into the drive.

I wondered what kind of moron would own such a gas-guzzling monster

these

days, when my question was answered by the driver who jumped out.

these

days, when my question was answered by the driver who jumped out.

My ex-husband, Roger.

What was he doing here, showing up unannounced, coming all the way from Chicago?

Wearing a navy jacket over a pale yellow shirt, and tan slacks, he hurried toward me, locks of his brown hair flying out of place, his normally placid features looking grim.

Immediately my adrenaline began to rush, and I flew down the porch steps to meet him, worried that something might have happened to our son.

“What is it?” I asked. “Jake?”

Out of breath, Roger asked, “Why haven’t you answered your cell? I’ve called and called!”

Taken aback, I sputtered, “I . . . I’ve been in the yard all morning and didn’t have it with me—what’s going on?”

“Is Jake here?”

“No! Why?”

His words came in a quavering burst. “I was afraid of that.”

“Roger! Stop scaring me.”

A deep sigh rose from his toes. “I think he’s run away.”

As confused as I was concerned, I asked, “Why would he do that? He seemed fine yesterday when I talked to him.” Then I frowned, recalling what our conversation had been about. “Only, uh . . .”

Roger gripped my arm. “Brandy, if you

know

something that might have motivated Jake taking off like this, you need to tell me

now

.”

know

something that might have motivated Jake taking off like this, you need to tell me

now

.”

Removing his hand gently, I said, “Roger, you better come sit down. Of

course,

I’ll tell you what I know. . . .”

course,

I’ll tell you what I know. . . .”

And turning, I led him toward the porch.

As we sat in matching rockers—like the married couple we’d be if I hadn’t ruined everything—I told Roger of my recent discovery of my true parentage: that thirty years ago, my older sister Peggy Sue had conceived me with then-state representative Edward Clark, while she had been a summer intern on his campaign. And that the grandmother I still called “Mother” had raised me as her own.

Roger’s shock morphed into irritation, his eyebrows trying to climb to his hairline. “And you thought this information should be shared in a

phone call

with an impressionable thirteen-year-old boy?”

phone call

with an impressionable thirteen-year-old boy?”

I spread my hands. “There was no other way—with the senator’s reelection campaign all over the news, my soap-opera parentage was going to be everywhere. I’m surprised you didn’t hear about it.”

He frowned, but his irritation had faded. “I’ve been away on business, pretty much constantly in meetings. When I got back, Jake was gone.”

“Have you notified the police?”

Roger shook his head. “Hasn’t been twenty-four hours yet. What a damn dumb rule! Don’t they say that the more time that goes by, the colder the trail gets?”

I stiffened. “You don’t think Jake has been

kidnapped?

Is

that

what you’re saying?”

kidnapped?

Is

that

what you’re saying?”

Roger certainly had the kind of money to warrant our son being that kind of target.

My ex leaned forward, rubbing his forehead. “No . . . no . . . I don’t think there’s much chance it’s anything like that. There’s been no phone call or note or any such thing.”

“Then . . . what

do

you think this is about?”

do

you think this is about?”

Roger took another deep breath. “Jake’s been, well, a lot more of a handful than usual. Acting out at school and at home. All because lately he’s been unhappy. He doesn’t say so, but it’s clear that’s the problem. That’s why I thought he might have come here. He’s always been able to talk to you.”

“What’s he unhappy about, Roger?”

He shook his head. “Who knows what a boy of his age is thinking? School, friends, girls, he keeps it all inside. His grades are okay but his teachers complain about his attitude.”

Suddenly I thought of someone who

might

know.

might

know.

“I’m going to ask Mother when she last heard from Jake,” I said, already on my feet. “You think he talks to me? He and his grandmother are thick as thieves, texting each other fast and furious.”

Which she’d just mastered, after having a cell for five years.

He nodded his okay and I left my dejected ex on the porch while I headed inside.

Just under one minute later, I returned. “You should come in,” I said, crooking a finger.

Roger followed me back in the house, and I led him into the dining room where Mother sat drinking a cup of coffee at the Duncan Phyfe table. She was wearing her favorite emerald-green pantsuit, her silver-gray hair neatly pinned in a bun, her magnified eyes behind the large glasses turned our way.

Next to her sat Jake.

He had on jeans and a gray sweatshirt with Chicago Bears logo, and held a can of Coke in one hand, while the other draped down, scratching the head of Rocky, the mixed-breed mutt (complete with black circle around one eye) that we had recently taken in.

Sushi—my blind, diabetic, brown-and-white shih tzu, the “child”

I’d

retained custody of after the divorce—sat a few feet away, her little mouth in a pout, apparently due to the attention Jake was giving the new-dog-on-the-block.

I’d

retained custody of after the divorce—sat a few feet away, her little mouth in a pout, apparently due to the attention Jake was giving the new-dog-on-the-block.

“Oh, hi, Dad,” Jake said, layering on a matter-of-fact attitude that didn’t fully mask his sheepishness.

For a moment Roger’s anger trumped his relief, but only for a moment. Father ran to son, throwing his arms around the boy’s shoulders, hugging him.

Roger quite naturally scolded Jake for disappearing; Jake just as naturally apologized to his father for scaring him; Mother came to the defense of her grandson; Rocky—a former police dog—growled at my ex for his threatening tone of voice; and Sushi started yapping, not to be left out. For a while, I was glad just to be an interested spectator.

But finally, to stop the commotion, I raised my voice. “Jake, how did you get here, anyway? And if you hitchhiked, please lie to me and say you took a bus.”

The boy looked my way. “I really did take the bus. Then walked from downtown.”

Mother said to me, “You were out back, dear, when he arrived, about forty minutes ago. You seemed to have a lot on your mind, and I didn’t want to disturb you.”

Before I could decide whether to shake her till her bridgework rattled or just kick her in the keister, Roger exploded, “Forty minutes!”

“Well, of course, that’s an approximation. . . .”

“And it didn’t occur to you, Viv, to

call

me? You didn’t think I’d be worried half to death?”

call

me? You didn’t think I’d be worried half to death?”

Mother lifted her eyebrows above the big glasses. “I

would

have gotten around to it, Roger dearest, but my immediate concern was that Jake was all right. Besides, talking to the boy, he indicates you’ve been away on business for several days, and called him only once.”

would

have gotten around to it, Roger dearest, but my immediate concern was that Jake was all right. Besides, talking to the boy, he indicates you’ve been away on business for several days, and called him only once.”

“That isn’t fair.”

“Leaving him alone in that big house. Why, he might have had one of those wild rock ’n’ roll parties you see in the movies! Dancing in his underpants and with nubile young things doing the boogaloo in bikinis around the backyard pool!”

“I wish,” Jake said.

Roger’s mouth was open, but words weren’t coming out.

Leaning against the doorjamb, arms folded, I said quietly, “Let’s not make a federal case out of it, Roger. Mother was dealing with things in her own inimitable fashion. Our son has been found, and he’s fine.”

Or was he?

Suddenly impatient, Roger tapped Jake’s shoulder. “Get your things, buddy boy.”

Uh-oh—“buddy boy” was never a good sign....

Roger was saying, “We’re going home

right

now.”

right

now.”

But Jake stuck his chin out. “I just got here,” he said stubbornly. “Why can’t I stay a few days?”

And before Roger could protest, Mother said, “I understand that the boy has all of this week off. A rare benefit of being in one of those year-round schools.”

Roger trained hard eyes on her. “And

you

want

me

to

reward

him for what he did?”

you

want

me

to

reward

him for what he did?”

“No, dear,” Mother said patiently. “Jake staying here for a few days wouldn’t be a reward exactly . . . more an opportunity for him to see that . . . despite this distressing news about our, well, family tree . . . nothing has

really

changed in our lives. Same-o same-o!”

really

changed in our lives. Same-o same-o!”

“Even

I

can see that,” Roger muttered, rolling his eyes. “Doesn’t seem to really matter which branch of the family tree

you

swung in on, Vivian.”

I

can see that,” Roger muttered, rolling his eyes. “Doesn’t seem to really matter which branch of the family tree

you

swung in on, Vivian.”

Did I mention that my ex never had gotten along with Mother?

Suddenly Jake’s eyes became moist. “Does this mean I have t’call

Aunt Peg

‘Grandma’?”

Aunt Peg

‘Grandma’?”

“Certainly not, sweetheart,” I interjected. “We’re not at this late date changing the lineup on the team. Peggy Sue is still ‘Sis’ to me. . . . Just because she screwed up as a kid, that doesn’t mean anything has changed.”

Roger gave me an arched-eyebrow look that said:

Screwed up? Really?

Screwed up? Really?

And I gave him a pained look that said:

Double entendre

not

intended.

Double entendre

not

intended.

Mother leaned closer to Jake, peering into his face. “And so

what

if I’m technically your great-grandmother? Can you imagine a greater grandmother than

moi?

”

what

if I’m technically your great-grandmother? Can you imagine a greater grandmother than

moi?

”

That made Jake smile. “You

are

great, Grandma.” He met his father’s eyes. “Can’t I stay, Dad? Please. I realize I was out of line, just taking off like that. Cut me a break, and I’ll clean up my act back home. I promise.”

are

great, Grandma.” He met his father’s eyes. “Can’t I stay, Dad? Please. I realize I was out of line, just taking off like that. Cut me a break, and I’ll clean up my act back home. I promise.”

Roger thought about it.

“Just for the week, Dad—I promise I’ll behave.”

Roger, with a half smirk, glancing Mother’s way (and mine), said, “It’s not

your

behavior that worries me, son.”

your

behavior that worries me, son.”

“Oh,

we’ll

behave,” Mother responded, smiling a little too broadly

.

Sort of like the Cheshire Cat in Disney’s

Alice in Wonderland

(cartoon version), right before he disappeared. “Won’t we, Brandy, dear?”

we’ll

behave,” Mother responded, smiling a little too broadly

.

Sort of like the Cheshire Cat in Disney’s

Alice in Wonderland

(cartoon version), right before he disappeared. “Won’t we, Brandy, dear?”

“Sure. You’re in luck, Roger. We’re not involved in a murder investigation at the moment.”

Roger shot me a reproachful glance. “I don’t really find that funny, Brandy.”

Wasn’t meant to be. It was

Mother’s

propensity for getting involved in such investigations that got us into trouble—not mine!

Mother’s

propensity for getting involved in such investigations that got us into trouble—not mine!

Jake jumped to his feet, threw his arms around his dad, gazed up with angelic innocence—it was over-the-top acting worthy of his grandmother. “Can I please stay?”

I already knew what my ex was going to say; I’d fallen prey to my offspring’s baby blues many times.

“All right,” Roger said, then waggled a finger. His next move on the parental/child chessboard was predictable and even kind of pitiful. “But when you get back, I want that room of yours cleaned.”

Oh, so very little has changed in the negotiations between kid and parent. Well, some things have changed—you used to get sent to your room for punishment. Now every kid’s room is a technological Briar Patch.

And before Mother could say something that would give Roger a change of heart, I offered to walk with him out to his Hummer, so we could finalize plans. Roger and I did get along, and we made a point of not using Jake to get back at each other.

As we descended the porch steps, I asked, “You’ll be back on Sunday, then?”

Roger, digging in a pants pocket for keys, responded, “Late afternoon. That way we can be home in time for Jake to clean his room.”

Did he

really

think that was going to happen?

really

think that was going to happen?

“I could meet you halfway on the interstate,” I offered.

Roger nodded toward the beast parked in front of his Hummer. “Not if you’re still driving that broken-down Buick.”

He had a point; last week a windshield wiper flew off while I was driving in pouring rain—luckily, on the passenger side.

We were by his Hummer now.

“Why don’t you get a newer car?” he asked. “I’ll buy it for you, if that’s the problem. . . .”

I looked at him sideways. Yes, we were on increasingly better terms, as the divorce faded into history; but things hadn’t gotten

that

much better.

that

much better.

Then my astonished ears heard myself saying, “No, thanks. The Buick keeps me from having to take Mother very far on her escapades.”

Wait, what? I could

use

a new car!

use

a new car!

He grunted. “Speaking of escapades—do you think you can manage to keep that woman out of trouble for an entire week?”

“I’m sure.”

“You are?”

“Pretty sure.”

“Nothing homicidal in the works?”

“Really, Roger. Get serious. It’s incredibly unlikely that Mother manages to get herself involved in these, well, mysteries as often as she has. This is a small town. If there’s one more homicide, the police will start looking at us as the real perpetrators behind all this carnage.”

He laughed. “You’re right. Statistically speaking, you’re safe. Another murder in sleepy little Serenity? Not going to happen.”

“Right.”

His eyes narrowed at me. “And there’s no other trouble she could get herself into?”

“I’m sure not.”

Pretty sure. Almost sure. Not sure at all.

He read my expression and asked, “She

is

current on her meds, isn’t she?”

is

current on her meds, isn’t she?”

I nodded; Mother was bipolar, which was why I was also current on my meds. Prozac.

“And you’ll keep a

really

close eye on Jake?” Roger was saying. “And call me if

anything

seems wrong?”

really

close eye on Jake?” Roger was saying. “And call me if

anything

seems wrong?”

Other books

Jennifer Scales and the Ancient Furnace by MaryJanice Davidson

The Weekend Girlfriend by Emily Walters

Youngs : The Brothers Who Built Ac/Dc (9781466865204) by Fink, Jesse

Exploding: A Mafia Romance (The O'Keefe Family Collection #1) by Tuesday Embers

The Game by Scollins, Shane

The Prisoner's Wife by Gerard Macdonald

Dead Dream Girl by Richard Haley

Stormbound with a Tycoon by Shawna Delacorte

The Final Exam by Gitty Daneshvari