Antiques to Die For (25 page)

“Josie!” Gretchen’s voice crackled on the intercom. “Fred wants to show you something.”

“Let’s go,” I told Paige.

As soon as we stepped inside the office, Fred handed me a collection of hand-written notes in a manila folder, and said, “I found it just this way.”

I nodded and opened the folder. The notes were written on steno-pad sheets, the top of each page frayed where it had been ripped from the notebook. I read:

Private Richard Windsor

•

recruited Kaskaskia, 1803

•

living in Sangamon River, IL???

•

joined L&C, Camp Dubois, 1 Jan 1804

More than two hundred years ago,

I thought,

about the same time as a British carpenter was building Rosalie’s desk

. I continued reading.

DOB—unknown

POB—unknown

Woodsman, hunter

Q:

1. Where was he from? (And when born?)

2. Where did he learn to read and write?

3. Formal schooling? (Records kept?)

4. Church records?

5. Harrison Bros. records?

His date and place of birth were unknown. So, too, it seemed, was his background. Rosalie’s notes went on for several pages. I was reading a scholar’s research. Evidently, Private Windsor was a member of the Lewis and Clark expedition. I wondered why she was interested in him more than any of the others. I skipped to the end.

Peabody Museum—Harvard

Nat’l Park Service—Oregon???

“Take a look at this,” Fred said. “It may relate to the same thing.”

He handed me a typewritten letter of agreement documenting the sale of a book called

The Private Journal of Private Richard Windsor.

The letter was dated March 4, 1981. Sarah Chaffee bought it from someone called Hayden Furleigh for $4,000, a huge sum for any but the rarest books back then, and still a substantial chunk of cash. I got an adrenaline rush.

Bingo!

I thought. Rosalie was right—potentially, the journal was of incalculable value. I glanced at the last entry I’d read:

Peabody Museum—Harvard

Nat’l Park Service—Oregon???

Were those two museums that housed documents Rosalie wanted to consult? I wondered. Or were those two possible buyers of the journal?

I turned to Paige. “Who’s Sarah Chaffee?” I asked.

“My mother. Why?”

“Who’s Hayden Furleigh?

“My aunt. Rodney’s mother.”

“Hayden and your mom were sisters?”

“Yes. Why?”

“We’re going through your sister’s papers, and there was a reference to them. Do you know anything about your aunt?”

“Not much. We didn’t speak to that side of the family.”

“I thought the breach was between your sister and Rodney?”

“I don’t think so. I think they inherited it. I don’t really know. Except that whatever it was about had something to do with money.”

“Fair enough,” I said, thinking that maybe Rodney would be able to shed some light on the issue.

“Good work, Fred. Outstanding. Is this everything? Are you done?”

“Yup.”

“Put everything in the safe, okay?”

“Will do.”

“And then go home!”

“Yeah,” he agreed, stretching.

I didn’t want to say anything to Paige until I had my hands on the journal, but I was so energized I could hardly contain myself from hooting and kicking up my heels. It looked like we’d identified Rosalie’s secret treasure. Standard operating procedure for a scholar would be to photocopy the journal to protect the original from wear and tear or harm. Assuming Rosalie had followed this protocol, where were the photocopied pages? And where was the original journal?

We’d need to go through every book on every shelf to see if she’d disguised the journal by slipping it into an ordinary dust jacket, a simple way to camouflage it from casual observers. I shook my head. From her own journal entry it was obvious that Rosalie hadn’t considered Cooper a casual observer. On the contrary, her assessment was that he was a thief. I wondered if he was a murderer, too.

My next step was to be certain we hadn’t missed the photocopy, but before I could ask Gretchen to get teams to Rosalie’s office at Hitchens and her house to pack up all of the books and remaining paper materials, the phone rang. It was Officer Brownley.

“I need to fax you the letter.”

“Sure.” I gave her the number.

Almost immediately, the fax machine whirred and clicked and a sheet of paper rolled out.

Dear Paige,

If you’re reading this, something’s happened to me. Not that I expect anything to happen to me, mind you, but you know me—I like to be prepared.

So, kiddo, here’s the scoop: We own a rare journal. Actually, calling it rare doesn’t begin to describe it—it’s darn close to priceless. I had to take it out of storage because Cooper was sniffing around. He saw a receipt from Tim’s where I was storing it and—surprise, surprise—got his own unit. I nearly fainted when I ran into him there! Knowing how much he wants to get his hands on it, I could just see him sneaking in a pair of bolt-cutters to break in and steal it. Anyway, the purpose of this note is twofold.

First, when you’re old enough, sell it. I hope a museum will buy it, but if you get a higher bid from a private collector, take it! I’m too romantic for my own good and it was a romantic notion to donate it. It’s appropriate to sell it, sweetie, so don’t hesitate. It’ll set you up for life—college, travel, everything. Talk to Josie Prescott. You know who I mean, right? My friend, Josie. She’s as honest as the day is long and will guide you in selling it for the best price.

Second, here’s where I put it—not ideal because of the harsh weather conditions, but at least it’s safe:

DZYNVMRL&X.

Love you to bits,

I took a deep breath and handed it to Paige. “Here.”

Paige read it slowly, then gave it back to me and sat in statuelike silence, rivulets of tears running down her cheeks.

Tears welled as I read her tribute to me, and I closed my eyes for a moment, willing myself to regain control.

“It sounds just like her,” I said after a moment.

“Did Cooper kill her?” she whispered.

“I don’t know, but you can bet the police are checking into it.”

I called Officer Brownley. “I’ve read it,” I told her.

“Obviously we’re following up on Cooper’s storage unit. My question to you is, do you or Paige know what those letters at the bottom mean?”

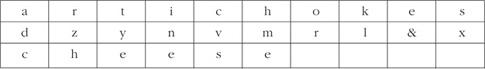

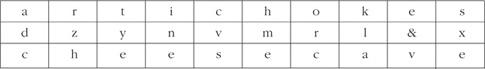

“Probably it’s the same code as in the kitchen. The artichoke code.”

“That’s what I figured. Can you decipher it for me?”

“Sure. I’ll call you back.”

As I hung up, I asked, “Do you want to decode it, Paige?”

She shook her head. I patted her shoulder, and said, “I’ll be down in a minute.”

Upstairs, I drew a three-row grid. I wrote

artichokes

across the top and

DZYNVMRL&X

in the center. One by one, I decoded the characters. Six letters in, I paused, certain I knew the answer.

I stared at the word. My pulse began to race. I stood up, then sat down, too agitated to stay still. “ ‘Cheese,’ ” I said aloud, took a deep breath, telling myself to focus, to slow down, and then, with a nod, I rushed to finish.

I hurried back downstairs. Paige hadn’t moved. Her cheeks were wet.

“Paige, do you have a cheese cave?” I asked.

“Yes,” she said, brushing away her tears with the back of her hand.

Gretchen handed her a tissue.

“Tell me about it,” I directed.

“We built it.”

“You and Rosalie?”

“Uh-huh.”

“Where?”

“In back of the house.”

I gawked at her. “The hill in the back corner?”

“Yeah.”

“You made a cheese cave?” I asked, flabbergasted.

Paige smiled as she patted away more tears, then twisted the tissue into a screw. “It’s not much of a cave. It’s kind of small.”

“Why did you make it?”

“For cheese. Rosalie thought it would be fun to make it ourselves.”

“What got her interested in making cheese?” I asked.

“A woman named Michelle Grover, I think her name is. Rosalie heard her speak at some lecture somewhere and got kind of excited. We got a book.”

The book on the kitchen counter

, I recalled. “What’s inside the cave?”

“Nothing. I mean, just the shelves, you know?”

“Tell me about it.”

“It’s small. It’s really just a dome covering a hole in the ground with some shelves and a really low ceiling.”

“A ceiling! That sounds pretty impressive.”

Paige giggled, her tears, for the moment, dried up. “You wouldn’t say that if you saw it. It’s just chicken wire, cement, and wood.”

I shook my head. “When did you build it?”

“Over Christmas break.”

“You did all that in one week?”

“It only took a few days—remember how warm it was over Christmas? It wasn’t all that hard.”

That’s just before Rosalie emptied her storage room at Tim’s

, I thought. Tingles of anticipation raced up and down my spine.

I picked up the phone. “Officer Brownley?”

“Were you able to decode it?”

“Yup. ‘Cheese cave.’ ”

“What is that?”

“I’ll meet you at the Chaffee house and show you.”

“No,” she said, and hearing the intensity of her response, I paused, fear returning. “I’ll come get you. I’ll be there in twenty minutes.”

I was in appraiser mode, eager to discover Rosalie’s—now Paige’s—treasure, and in my enthusiasm, I’d lost sight of the larger issue. Rosalie had been murdered and her killer was still at large—and, from what I could tell, as we were circling closer and closer, the police thought there was a chance that the murderer had set his sights on me.

CHAPTER THIRTY

O

fficer Brownley stepped inside, setting the chimes jingling. “All set?” she asked.

“Give me one sec,” I said, and ran up to my office. I dialed her cell phone. “It’s me from upstairs. I didn’t want to discuss Cooper in front of Paige, but I need to tell you something right away. You know how Rosalie wrote in her diary about catching Cooper with a copy of her journal pages in his hands? We’ve finished going through her papers—there’s no such copy. Apparently it’s missing.”

She paused, considering the implications. “Thanks.”

Downstairs, I grabbed my toolbox in case we needed to open a chest or some mechanism in the cheese cave. Officer Brownley drove.

I’d offered Paige the opportunity to stay at the office and hang out with Gretchen, but she’d chosen to come along. In her shoes, I would have done the same thing.

It was another sunny day, though not as mild as yesterday. Sunlight warmed the New Hampshire winter colors, various shades of brown and gray, lending them resonance and richness.

No wonder Evan Woodricky chose to stay in New Hampshire to paint

, I thought.

Browns and grays aren’t only the shades that Whistler preferred, they’re also the colors of New Hampshire in winter

.

All at once I realized that I hadn’t heard from Wes in response to my question about what happened to Rosalie after she had drinks with Gerry, and then a moment later, it occurred to me that I hadn’t checked my voice mail. I patted around inside my tote bag until I found the disposable cell phone Officer Brownley had bestowed on me. It felt odd in my hand.

Sure enough, Wes had called.

“So the answer is that I don’t know and I don’t think anyone else does either. No one admits driving Rosalie anywhere. According to my police source, both Gerry and the driver say that Gerry got in his limo alone and went straight home. I heard that Gerry’s now saying he didn’t see Rosalie that night at all, that it was a different night. Even though the bartender says otherwise, try and prove it’s a lie. The lounge was packed, so how can the staff be a hundred percent certain it was

that

night she was or wasn’t there? Anyway, that’s it. . . . Whatcha got for me? Call me.”

I closed the phone and slid it back into my tote bag. I shrugged. I was glad when we turned onto Hanover Street and I could stop thinking about where poor Rosalie had been the night she was murdered—and whether someone, most likely Cooper, had lured her to her death.

Pulling up to the house, Officer Brownley hit a huge puddle and cascades of water streamed up on either side of her patrol car. She parked close to the banked snow, and we piled out.

With Officer Brownley and Paige close behind me, I trudged through the yard. I used my arm to sweep away the heavy, wet snow that blocked access to the cheese cave.

The doors were reminiscent of those used in storm cellars, two wooden panels lying at a moderate angle, hinged on the outside, and braced with a crossbar. In the center of the crossbar was a lock.

“Okay,” I said, “here goes nothing.”

The key I’d found hidden in Rosalie’s toiletry box fit, and the doors opened easily. I smiled in eager anticipation, dropped to my knees, and leaned in.

My little flashlight lit up white-washed, dimpled concrete walls and a single row of wooden shelves, maybe ash.

Not bad

, I thought,

for two amateurs and a few days’ construction

. Within easy reach, I saw a tan metal box.

“There’s a box,” I called, my words muffled and echoey in the airless chamber.

“Don’t touch it without gloves,” Officer Brownley instructed.

Gingerly gripping the handle on the top, I slid it toward me and shone my light around one last time to be certain I hadn’t missed anything. I stood up and relocked the doors while clutching the metal box to my chest, as if it were gold.

“Got it,” I said.

I sat in the front seat next to Officer Brownley. The box rested on the seat between us. Paige was in the back.

Wearing plastic gloves, Officer Brownley unhitched the latch. Inside was an unsealed, padded envelope, the kind used to mail fragile items. She wiggled it out. Inside the envelope was a see-through plastic baggie, and inside the baggie was a leather-bound book. She reached into her coat pocket for another pair of plastic gloves. Once I had them on, she handed me the baggie.

I extracted the butter-soft volume from its plastic container, and carefully opened it. The title page read,

The Journal of Private Richard Windsor

. It was hand numbered, in an elegant hand,

12 of 20

, and it had been printed by Harrison Brothers of Boston in 1809. I turned a few pages. Even through the gloves I sensed that the paper felt right, heavy and cottony. At first glance, the volume appeared to be in mint condition. I opened to page one and began to read.

“Not one among us knows that I can read and write,”

it began,

“and I do not intend to tell them. The less the others know, the better it will be for me. When they think you are less educated and knowledgeable than they are, they talk more openly and with less discretion.”

“What is it?” Officer Brownley asked.

“I’m not sure.”

This one slim volume was, without question, valuable. But whether it was worth a few hundred dollars, as any leather-bound book in excellent condition from that era would be, or tens or hundreds of thousands—or more—required research.

Officer Brownley watched as I repackaged the book.

“I’ll need to take the book in for forensic examination,” Officer Brownley stated.

I chose my words carefully. “I understand that there may be forensic evidence that you need to collect. But you should have an expert there to ensure that you don’t damage it.”

“Like you?”

“Yes.”

Paige asked, “May I see it?”

“Sure.” I carefully extracted it from the metal container and padded envelope. I held it up, still inside the plastic bag. “We shouldn’t touch it any more until after the police finish with it.”

She nodded and stared at the cover.

“It’s old, huh?” Officer Brownley said.

“Yeah.”

“So why is it rare?” she asked. “Because it’s from the early eighteen hundreds?”

“Certainly that’s one reason. And it’s in pristine condition. And, evidently, only twenty copies were printed, which means it’s scarce. Who knows how many of the other copies exist, so it’s also probably rare.”

“Does it matter what the book is about?”

“Absolutely. We need to research it, but if Richard Windsor did, in fact, write this journal while on the Lewis and Clark expedition, it’s priceless. It’s of indescribable historical importance.”

“Which is why Cooper wanted to steal it,” Paige interjected, sounding angry.

“We don’t know for sure that he did want to,” Officer Brownley cautioned.

“Rosalie said so in her letter.”

“I know, and we’re investigating it. But we shouldn’t jump to any conclusions.”

Paige, sitting in the backseat, her arms folded across her chest, seemed utterly unpersuaded by Officer Brownley’s reasonable comment. From the look on Paige’s face, she was ready to round up a posse and lynch him before nightfall.

“Do you think Ms. Chaffee told anyone about the journal?” Officer Brownley asked me.

“Her book editor,” I replied, easing the journal back into the padded envelope and sliding it into the box. “My guess is that’s it.”

We discussed logistics and Officer Brownley agreed to drop us at Heyer’s so I could hang another painting. She glanced at her watch. “I’ll call the tech guys while you’re there and set something up so you can talk to them before they begin.”

“Can I come inside?” Paige asked. “I’d like to see where Rosalie worked if that’s all right.”

I agreed as Officer Brownley pulled to a stop at the front door. “Call me before you come out,” she instructed, and the hair on the back of my neck bristled.

Inside Heyer’s, Paige and I signed in at the reception station.

“Hey, Josie! Aren’t you an early bird!” Una said.

“Am I? What time is it?”

“A little after nine—not so early, I guess.”

“Well, let’s hope I catch a worm regardless,” I replied, then realized how stupid that sounded, and laughed. “Well, actually, I don’t want a worm. I’m just here to hang a painting. Have you met Paige?”

“I think so. At last summer’s company picnic, right?”

“That was a fun time,” Paige said, leaving it open as to whether they’d ever met.

“I liked Rosalie a lot and I’m really,

really

sorry for your loss,” Una said.

“Thank you,” Paige murmured, looking down.

“Why don’t you wait over here until I see if it’s all right for you to take a look at Rosalie’s office, okay? I won’t be long.”

“Okay,” she said, taking a seat in the far corner.

I greeted Tricia, then pointed to the still-crated James Gale Tyler seascape. “Would you let Gerry know I’m here? I’d like to hang it if I can.”

She picked up her phone and buzzed through. “Josie’s here to hang the painting.”

“Josie!” Gerry shouted, sounding as buoyant as ever. Tricia hung up the phone as Gerry poked his head out of his office. “Great to see ya, doll,” he told me, winking. “Go to work!”

I pried open the crate, then wrestled the painting out. As I set aside the container, I suddenly had a thought. After Gerry left The Miller House, perhaps Edie followed Rosalie home. Edie could have suggested that they talk about the situation calmly, like adults, and Rosalie, naive and optimistic and deeply in love, agreed, and got in Edie’s car.

Edie might have taken her to a quiet place—the Rocky Point jetty, for instance. Maybe she intended only to talk, but Rosalie, euphoric and thus reckless, refused to give up Gerry; probably she even refused to discuss it, instead suggesting that Edie resign herself to the inevitable, and so from Edie’s perspective, there were no other options—Rosalie had to die.

Then I thought about Cooper. He had no alibi, which meant that the same time sequence would work for him, too. If he was desperate to get Rosalie to stop her legal actions against him, he might have wanted a private talk. Maybe he followed her, waiting for an opportunity to persuade her to discuss the situation one-on-one, without lawyers. Rosalie, riding high with a book contract and secure in the knowledge that the journal was safe, might have stepped voluntarily into Cooper’s car. It wasn’t a stretch to imagine Cooper’s jealous rage exploding in one disastrous strike.

I shook off the frightening image and breathed in deeply. Finally I turned to Gerry and forced myself to focus on the task at hand.

“So I’m still going to hang the Tyler here, right?” I asked, pointing at an area above two club chairs set off to the side.

“What do you think? Should we hang it in Ned’s office?” he asked, squeezing my arm. “He said he likes it.”

“Ned?” I repeated, surprised. “Ned likes Western themes, not maritime art. Did Ned say he wanted this piece in particular?”

“Not directly,” he replied with a wink. “He admired it, so I said to myself, let him have it. Ned’s a helluva trooper, ya know? CFO of a company like this with a CEO like me . . . ,” he said, trailing off into a guffaw. “I owe that dude a lot.”

“It’s up to you, of course, but the Sharp was a very generous gift.”

“Thanks, doll. But with the board meeting coming up, well, let me just say that he’s risen to the occasion—really acted above and beyond the call, you know what I’m saying?”

I didn’t have any idea what he was saying and paused to give myself time to think. “Whatever you want is fine with me. How about if I offer him the choice—the Tyler or another Western scene?”

He smiled broadly. “That’s a killer idea, doll.” He rubbed my arm and I drew away.

“If he chooses a Western-themed object, we could sell the Tyler to pay for it.”

“Nah, it’s only money, right, doll? But I like the idea of asking him. It’ll be a sign of respect.” He chuckled, amused at I didn’t know what. “Whatever you think is best, you go ahead and do. I know you won’t rook me.”

“Sure. I’ll take it over now,” I said, glad for an excuse to leave Gerry’s presence. He gave me the heebie-jeebies.

“I’ll catch ya later, doll,” Gerry said, swinging his coat over his shoulder. To Tricia he added, “I’ll be at that meeting. Should be back after lunch. Ya need me, ya call.”

“Yes, sir,” she said.

I selected the tools I’d need to hang the painting from the toolbox I kept near Tricia’s desk, then carefully picked it up and headed out of the anteroom. “Tricia, would you ask Una to send Paige back here? Paige is Rosalie’s sister, and wants to see where she worked.”

“Poor thing.”

I stepped into the corridor and waved to Paige as she turned the corner. “I need to show this painting to someone,” I told her, pointing toward the seascape. “Would you keep me company? You can see Rosalie’s office in a few minutes.”

By the time we got to the other side of the building, my arms were feeling it and I was glad to lean the painting against Ned’s assistant’s desk. I greeted her, introduced Paige, and surveyed the anteroom. There was no obvious place to hang it. The walls were full, overdecorated, in fact. There were three paintings of the Rocky Mountains, one of cowboys sitting by a camp fire, another of a cowboy on a cliff, and several framed artifacts.

“Josie!” Ned said, stepping out of his office. “Paige,” he added, “long time no speak.”

“Hi, Ned,” Paige said.

“Sorry about Rosalie. Quite a shock.”

She nodded and looked down.

“Sorry I couldn’t make the tag sale on Saturday, Josie.”

“You will sometime,” I said.

“Gerry said you were going to be working in

his

office this morning. Did our faithful leader chase you away?”

“No,” I replied, wishing his sarcasm was less biting. “He wanted to know whether you’d like the Tyler.” I picked it up and held it high so he could see it at eye level.

“What do you think of it?” Ned asked.

“I love it,” I said. “Tyler’s one of the best. He really captures the feel of life at sea. Look at the billowing sail—can’t you just hear that wind?”