Appetite for Life: The Biography of Julia Child (76 page)

Read Appetite for Life: The Biography of Julia Child Online

Authors: Noel Riley Fitch

Tags: #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #Child, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #Women, #Cooking, #Cooks - United States, #Julia, #United States, #Cooks, #Biography

Morrow made the winning bid with A La Carte Communications to publish the book, including payment for all photographs. Whether Knopf would have matched the bid no one will know, but it is doubtful. A La Carte received far more money than expected, and misleading reports that Julia always kept her electronic rights became big news. Writers from around the country called her for advice on retaining their electronic rights, just as they did when the

New York Times

decided to claim copyright on all articles written for the paper (Pépin announced he would no longer write for the

Times)

. These two issues would define writers’ battles for claims to their work during this decade, and many turned to one of the oldest members of their profession for advice and leadership.

Drummond’s budget for his master chefs and bakers series (about $35,000 per episode) compares with the cost of a half hour of Martha Stewart ($90,000), but contrasts dramatically with the millions spent for each episode of a weekly drama like

E.R

. or

Law & Order

. These relative costs explain the growth of (inexpensive) cooking shows on television. Yet the search for sponsors was never easy because PBS policy limits all advertising to a preliminary half minute. Part of Julia’s contractual agreements on the last few series involved help and support (though not endorsement) for their major sponsors, including Land O Lakes (they used 753 pounds of butter for the baking series) and Farberware. PBS contributed part of the funding and benefited most from the programs. A La Carte Communications and Julia, partners, benefited from book sales, which is why Julia was the chief promoter of what she honestly called “Dorie’s book.” This gracious honesty on celebrity-drive QVC “killed the book,” said one publicist, and they sold one fifth the books she had on her previous appearance.

Drummond used three cameras for the baking series and made thirty-nine shows with twenty-six bakers, thus ensuring a regular slot in the season repertoire of local PBS stations. According to several of the crew, the major problem in making the series was in team morale when the ever-loyal Julia insisted Nancy Verde Barr be appointed associate producer. Baking was more complicated to dramatize in the filming, according to Drummond, because the magic occurs inside the oven. Thus, at one point they had seventeen bread machines working: “If we lost a bread in the middle of a second rise, we would need a second bread and a third bread.” When Julia watched Mary Bergin caramelize the sugar on the crème brûléed chocolate bundt cake with a blowtorch, Julia remarked, “I think every woman should have a blowtorch.”

Baking with Julia

was shown thirteen shows per season in 1996 and 1997, featuring bakers like Michel Richard, who began his career with the famous French pastry chef Gaston Lenôtre; Lora Brody, who founded the Women’s Culinary Guild and made the bread machine a common household appliance; Martha Stewart, who made “One Glorious Wedding Cake;” and Craig Kominiak, the tall and handsome baker of the Ecce Panis Bakery in New York City. “A real man,” Julia purred upon seeing the tall, burly baker.

Fame came to Julia when she was mature, and she handled it with what Fred Ferretti in

Gourmet

called “an innate ease” and grace, occasionally even being surprised by it. She had lived now so long that she was famous for being well known (no doubt the definition of an American celebrity). She became what one writer called “a familiar object next to which people might pose for photographs.” But unlike Woody Allen, Charlie Chaplin, and Martha Stewart, the public has never turned on her. She never suffered the “perils of persona.”

“Fame is a fickle food upon a shifting plate,” the poet Emily Dickinson wrote in the nineteenth century. Julia seemed aware of this New England wisdom, and with the help of Bill Truslow’s eye on “quality control” she kept her integrity, nurturing the national hunger for the famous, so that she could keep doing what she loved to do and avoid loneliness and boredom. She was observed by a local journalist greeting guests at a garden party in Woodstock, Vermont, in the summer of 1996. She appeared to be like the queen mother, the observer thought: “If her public demeanor is one of bemused acceptance of the attention showered on her, her private aspect is of an elderly and omniscient bird who keeps her own counsel and is rather less reverential than the treatment accorded her.” Both R. W. Apple, Jr., and Dun Gifford, on separate occasions, compared her to Michael Jordan: at the pinnacle of her career, she remains an American icon who transcends a single task or definition.

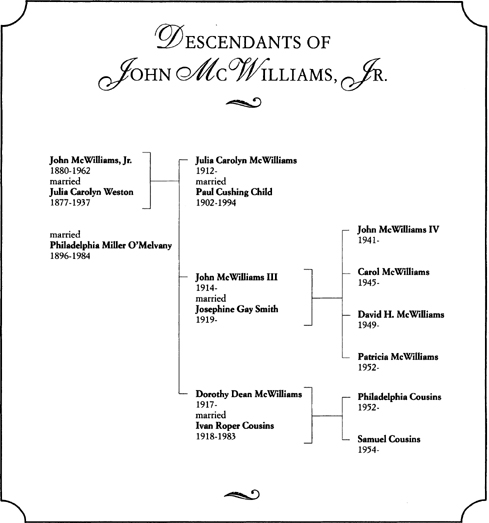

The changes in her private life came as a result of her aging. After her friend John McJennett’s health began to fade, he was put into a nursing home, where he died of bone cancer in February 1996. “All my California friends are dropping like flies,” she reported just after the deaths of Robert Hastings and Jack Wright. Then George Kubler and Mary Ripley died. “Woe,” she often said. When his health weakened, her brother John and his wife moved into a retirement home. She wanted her family close to her, and she talked to Dorothy regularly. She found her renewal in other people (“My greatest happiness is a good meal with friends”) and in short catnaps. She never joked about her age and denied ever having jet lag or fatigue. She possessed what Margaret Mead had said were the prerequisites for any American woman to succeed: superhuman energy and an ability to outwit the culture’s plans for her.

She always kept her private life private, even from her closest professional friends. In 1995 Jacques Pépin thought that she had children, and Dorothy Cann Hamilton said she did not think she really knew Julia. Her personal assistant Stephanie Hersh was never an intimate. A friend with whom she traveled for years said, “I do not really know Julia.” She was a social and physical animal, not a philosophical one. She remained, in her eighties, the girl who adored peanut butter and raw dough, who cried at movies and loved cats. She had a huge collection of rubber stamps, many of them images of cats, which she would imprint on the bottom of notes. She laughed at dirty jokes and planned parties, did not take herself seriously in private, but steeled herself publicly. She was generous, tough, and stubborn.

Her friend M. F. K. Fisher said of herself that age meant she could “get away with more. Say more of what I want to say and less of what people want to hear.” Julia also got past what Fisher called the “protective covering of the middle years” and became more incautious and obstinate. All her traits became exaggerated, said Anne Willan. A former school friend said she had “grown more caustic than she used to be,” taking on some of Paul’s attitudes. “She could be magisterial and imperious,” said yet another. She had the stubbornness of Greta Garbo, the independence of Katharine Hepburn.

In January 1997 in Santa Barbara, she put the Seaview condominium up for sale and moved her furniture into storage and bought a private dwelling in a retirement village that she and Paul had chosen years before. She would not burden loved ones with any future infirmities (she thought); she was alone (she felt). She would keep the Cambridge house and office a few years longer before giving it to Smith College. She continued to teach and sell books, but perhaps her greatest triumphs came through television. Betty Fussell called her “a major woman television comic second only to Carol Burnett and Lucille Ball.” Yet her true impact on television was changing the country’s views on the importance of good food and good dining—while giving them a good show.

The passion for cooking that had gripped Julia in 1949 in Paris was finally legitimized in her own country. By 1997, the Bureau of Labor Statistics reported that the food service industry was the “fourth fastest-growing” in the country, a figure echoed by the National Restaurant Association’s estimates that by 2005 there will be “1.5 million new restaurant jobs” available. The nearly 300 chef schools could expect “an average of six to seven job possibilities for every chef and baker they graduate.”

The television audience Julia began gathering in 1963 had burgeoned by 1997. One third of the programs of PBS, which now reached 98 percent of all homes, were cooking shows. When they were joined by TVFN, which claimed 17 million cable subscribers, and the cooking programs on the Discovery Channel and the Learning Channel, one executive was prompted to claim, “Food is the live entertainment of the future.”

M. F. K. Fisher and A. J. Liebling

(Between Meals)

may have first made it acceptable to love food and talk about it, but Julia spread that gospel to the middle class. She is most proud of bringing men into the American kitchen. Yet Christopher Lydon, in one of the best profiles of Julia in 1996, believes her impact was greatest on women: “Queen Julia has done more than [Betty] Friedan, Gloria Steinern and Co. to show American women a model of power in public and expressive self-discovery at home.”

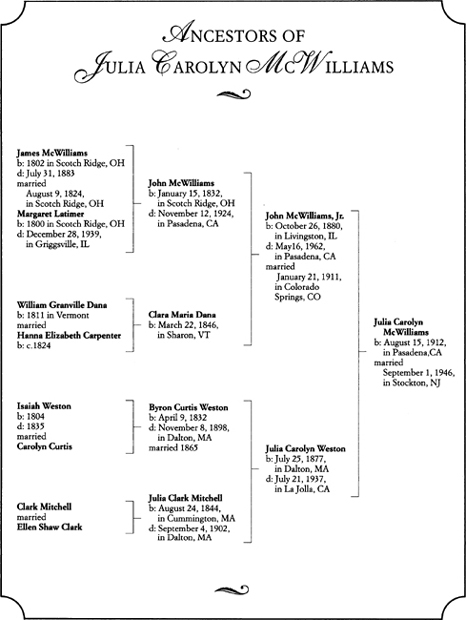

Her career, and the example of John McWilliams and Paul Child, had turned a happy-go-lucky, aimless tennis player into a world-class educator and inspiration, what some called a workaholic (she herself would reject the word). “She fears death,” says one of her family members. “I think that she fears if she stops she will die.” At least she dreads professional death, for she loves what she does; if she stops she might be forgotten and not be able to continue.

H

ER LAST SUPPER

The meal would begin with foie gras, oysters, and “a little caviar.” For thirty-five years she was repeatedly asked for the menu of her last meal. For one who loved a simple, well-cooked piece of meat and a ripe pear for dessert, she always named the most extravagant and rarest foods for her last repast:

First, caviar with Russian vodka (Duburovna) and oysters with Pouilly-Fuissé. And some foie gras, of course. Second, she wanted to eat pan-roasted duck—the duck never varied—accompanied by little onions and chanterelle mushrooms, her main dish. Sometimes she mentioned

pommes Anna

, “that lovely cake of sliced potatoes baked in butter to a crisp brown crust.” Sometimes she wanted fresh asparagus with the duck. She would drink a 1962 Romanée-Conti, which she had had only once, for it cost $700 a bottle. When she was in a frugal mood, she chose a delicate red Bordeaux, a St.-Emilion or Château Palmer. Sometimes, Château Lafite-Rothschild. Third, good French bread with Roquefort and Brie would be eaten with a great Burgundy, such as Grands-Echézeaux.

Finally, dessert was a movable feast on which she changed her mind over the years. It varied from pungent sorbet with walnut cake to a simple ripe pear and green tea. She was never strong on desserts, but as she got older she decided she could eat a gooey chocolate dessert or a charlotte Malakoff. When she dreamed big, her dessert was the crème brûlée from Le Cirque with Château d’Yquem 1975 or 1976 at $450 a bottle.

“And I would die happy.”

When she was asked for her “favorite comfort food,” she responded firmly, “Red meat and gin!” A pioneer of pleasure in a puritan country. A sturdy “pre-war feminist,” as Camille Paglia, the author of

Sexual Personae

, describes women like Julia Child, Amelia Earhart, and Katharine Hepburn. Paglia, once called a “motormouth gender contrarian,” calls Julia Child “a major American woman” who has been neglected by the academic feminist establishment (“the anorexia- and bulimia-obsessed victimology of academic studies!”) because Julia is the “opposite of today’s victim psychology”: “This country was a waste-land of Philistinism in terms of food until (‘food-affirming’) Julia Child came on the scene…. [S]he is one of those figures in history who totally transformed American culture.”

In her old age, Julia joined that noble species, the Grand Old Gal—a common apotheosis for brilliant women. She may stand with her head tipped a little down and sideward, as Eleanor Roosevelt did when her back became stooped, but she is still the queen. Despite bum knees weakening her gait, and the occasional need to lean against the stove (or on the table), she worked at a barely diminished pace. After all, as she loved to point out, “Escoffier lived to be ninety-three and my old chef Max Bugnard lived to be ninety-six.”

Her appetite for life will never be sated. “Retired people are boring,” she claims. “In this line of work, you never have to retire. You keep right on until you’re through.”