Apprehensions and Other Delusions

Read Apprehensions and Other Delusions Online

Authors: Chelsea Quinn Yarbro

Tags: #Chelsea Quinn Yarbro, #Horror, #Dark Fantasy, #Science Fiction, #short stories

I first met Chelsea Quinn Yarbro back between the 8

th

and the 9

th

Punic Wars (she was a mere babe in arms at the time) in 1976, when I read her novel,

The Time of the Fourth Horseman.

I

was so impressed that I called her up ... and promptly got into an hour-long conversation that ranged over religion, politics, military history, music, and the Science Fiction community—of which we were both relatively new members. It was fascinating, wonderful and

fun

... and every single conversation we have had since then has been exactly the same. I’m not the only one who feels this way about conversations with this dear lady, by the way. I soon discovered that she possessed more than a few talents: composer, cartographer, playwright, student of seven different instruments, as well as voice, tarot card reader, and author of wonderful novels encompassing a number of genres—even Westerns,

The Law in Charity

and

Charity, Colorado

(believe me when I tell you this) are unlike any Westerns you have ever read; they are well worth looking up.

As you might have guessed, we’ve been friends for quite a while. Chelsea Quinn Yarbro is interesting, talented, good-hearted, intelligent, and has one of the greatest smiles that has ever shone anywhere. And she introduces me to wines that, when I drink them, I think the world is a pretty nice place after all.

Well, that’s nice,

I heard someone say.

The two of you are good friends. But what does this have to do with this collection of stories?

Okay, I’ll tell you.

All of the qualities named above go into everything she writes. And her style is measured and elegant and just plain musical. Her stories contain the most amazing historical, literary and imaginative details. Her characters are weird and multidimensional and achingly familiar. She writes about love and survival and stress and violence and the incomprehensible contrariness of the human spirit. (Therefore, we must add courageous to the list of qualities possessed by this author. Please make a note of this.) The universe and our fellow human beings and even ourselves do things—sometimes horrible things. It is a writer’s duty to face them, to stand up to them and not to blink. Chelsea Quinn Yarbro

never

fails to confront each and every one.

Each of the stories in this volume, written between 1982 and 2002, whether Horror or Science Fiction or just Fiction, are lovely representatives of the above—

Do

you have any favorites?

(There is that person again. Who is that? Stop interrupting when LoBrutto is composing.)

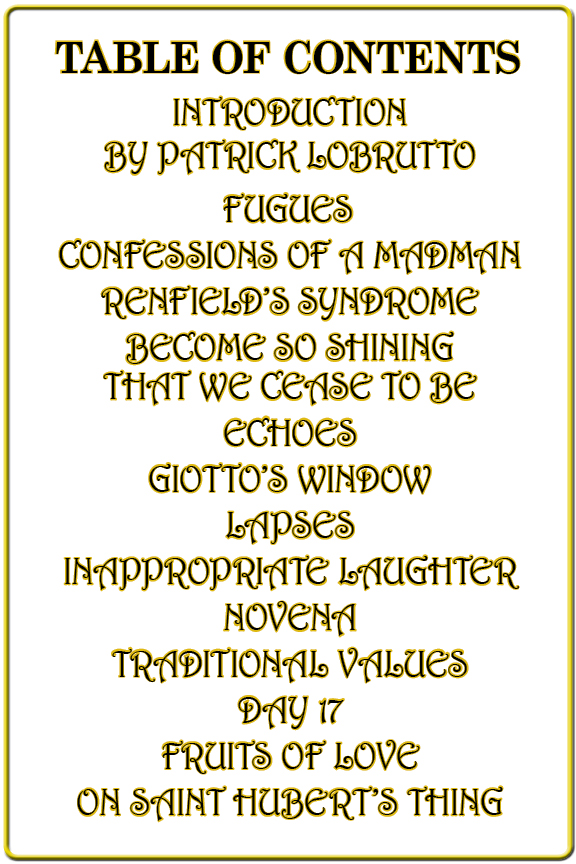

Well, yes, I do. I thoroughly enjoyed reading every story in this collection. I have truly never read anything by Chelsea Quinn Yarbro that I didn’t enjoy. Some, however, do stand out in my mind: “Fugues” is just the kind of story Quinn would write, a Grand Toccata and, uh, well, Fugue on a fairly common theme in supernatural short stories (it’s anything but common in the hands of this author); then there’s that tasty morsel, “Renfield’s Syndrome” about the joys of being carnivorous; “Become So Shining That We Cease to Be” (I do so love that title) a very neatly constructed story on the lengths some people will go to in order to be heard; “On St. Hubert’s Thing” is the type of story Quinn does so well, an intricately detailed story of plots and heresy and faith.

Waste no more time, gentle reader; move on to tales of wonder by the incomparable Chelsea Quinn Yarbro.

—Patrick LoBrutto

VANESSA HYLAS

ran

her fingers lightly over the curve of the forte-piano, enjoying its long, narrow shape—more like a boat than a harp—even as she pondered how she would contrive to keep the two-hundred-year-old instrument tuned through an entire recital. “We’ll have to have two intermissions,” she told her manager as she continued to caress the glossy wood. “And retune it both times.”

“That shouldn’t be a problem,” said Howard Faster, making a note on his Palm Pilot. “I think people will make allowances for the instrument. This isn’t just any antique. It

is

the Dziwny forte-piano—the very one he ...”

“He killed himself playing; yes, I know,” said Vanessa, more bluntly than she had intended. She coughed and spoke again, more gently. “Stasio Dziwny performed for the last time on this instrument. It was December 8

th

, 1803, if I recall the date, a pre-holiday private concert at his patron’s most important Schloss, Schloss Lowenhoff. There were about fifty people present, not counting servants, according to what I’ve read.” Her shiny, close-cropped, dark-blonde hair was starting to pale around her face, the fluctuating shade not unlike the beautifully grained wood of the fortepiano’s case. At forty-three, she had grown into her angular features and was much more attractive than she had been in youth, something she recognized with a trace of humor. She held herself well, almost as if she were about to play for an audience rather than test an old instrument for the first time.

“Yes,” said Faster, fussing with his expensive regimental tie. Smoothing his thinning, colorless hair with one blunt-fingered hand, he looked around for the warehouse manager among the vast collection of pianos. “It amazes me that it’s in such good condition, considering where it’s been for the last couple of centuries, or almost a couple of centuries. It’s a miracle they found it.”

Vanessa nodded. “In an attic in an Austrian Schloss—not Lowenhoff; Schaumbach, or something like that—according to the documents; you saw them,” she said, repeating what she had been told just four days ago. “Stored away in a sealed room on the top floor. You wouldn’t think the Graf would care to keep the thing, even locked away like that, if the stories about it are true, and considering his family’s role in what happened.”

“Perhaps he wanted to make sure it never got used again,” Faster suggested. “You know, take it out of circulation.”

“If that was his intention, he did a great job with it,” said Vanessa. “It makes the provenance a simple matter.”

“Well, yes; the documents look to be authentic,” said Faster in a resigned tone of voice. “They’ve been vetted legit. All the tests have come out supporting the claim. This is the Dziwny forte-piano.”

The two were silent as Vanessa pointed to an irregular stain on the bass end of the keyboard. “Brown. It could be blood.”

“It could,” said Faster uneasily. “Or something from being stored that way, or a natural discoloration of some sort. You can bet the Graf had it cleaned.”

“A man blowing his brains out all over a forte-piano must have been messy, much more than this stain’s-worth—there’d be blood and skull fragments, and brain matter, according to what I’ve researched; those old pistols did a lot of damage,” said Vanessa distantly. “I would have expected ... I don’t know: something a lot worse than this.” She pulled the bench out and sat down at the instrument, trying an experimental chord.

A jangle of untuned strings shuddered out of the forte-piano.

“Ye gods!” Faster exclaimed. “They said it would be tuned.”

“Not yet,” said Vanessa, pulling her hands back as if scalded. “There are strings to be replaced, I’d have to say. They’ll need to give it a thorough going-over before it’ll be ready for the public.”

“No kidding,” said Faster. “I’ll call Shotwell right away. This is not the sound we want; I don’t care how authentic it is. He’s got to improve it.” He pulled his cell phone out of his breast pocket and tapped in a ten-digit number, then turned away to create the illusion of privacy.

Vanessa made a point of ignoring Faster’s end of the conversation, putting all her attention on the forte-piano. She played a few of the keys, her touch unusually hesitant, and winced at the sound the ancient, neglected strings made. At last she contented herself with playing one of Dziwny’s own compositions half an inch above the keys, hearing the correct notes in her mind. Only when Faster was through did she relent, swinging around on the bench and looking directly at him. “Well? What did he say?”

“He said he’d arrange everything, since he knows you want to perform with it,” said Faster, frowning as he spoke. “You wouldn’t believe what he had the nerve to tell me.”

“He said he couldn’t get his usual restoration crew to work on it,” she said promptly.

“You overheard,” Faster accused.

“No. It’s just a guess. But you’ve read the historical material about it, and you can bet Shotwell’s crew has, too, and know about the stories they’ve told about this instrument. It’s one of the most enduring fables in the classical music world, the forte-piano that compels those who play it to commit suicide.” She laughed. “Only one suicide has ever been proven in relation to this, and that was Dziwny’s own; the instrument’s been missing for close to two hundred years, so there’s no other accounts of it doing in anyone else. The Graffin died some months later in childbirth, not at the keyboard. And it turns out now that the forte-piano was put into the attic shortly afterward, so no one else had the chance to kill themselves while playing.”

“How do you account for the stories, then?” Faster asked, interested for promotional reasons.

“Because there was so much scandal around Dziwny’s love affair with the Graffin, assuming the rumors about the affair were true: there’s no proof that it was ever anything more than gossip. Still, it was quite an occurrence. His suicide was so dramatic. The public loved ghost stories back then, and the events were irresistible. And there was that awful book that came out in 1850, turning the whole story into a complicated Byronic romance. It’s become difficult to separate fact from fiction.” Vanessa laced her fingers together and looked directly at Faster. “How long is it going to take, getting this ready?”

“Shotwell said probably a month,” said Faster.

“That cuts into the Canadian tour,” Vanessa reminded him. “But that might be useful. We could use the tour to generate some interest in this instrument.”

“Sounds good to me,” said Faster, who was in favor of anything that could end up making Vanessa, his client, more money, for he would share in her good fortune.

“Then let’s plan on it,” she said, rising. “I want to find out everything he played that night, the night he shot himself.”

“Good God, why?” Faster asked.

“Because I think it would make for a very special first concert on this instrument,” she said, running her fingers lightly over the side of the forte-piano. “Think of the interest we could generate. And the myths we could put to rest.”

The promotional possibilities began to percolate in Faster’s agile brain. “Not a bad idea, Vanessa,” he approved. “Not a bad idea at all.”

* * *

Nicola van der Beck looked up from the stacks of books on her cluttered desk and managed a vulpine smile, the lines in her face punctuating her look of eager predation. She held up an old journal as if offering a jewel to Vanessa. “It took some doing,” she said proudly, “but I finally found a full account in this. The Baron Gewaltheit. A dreadful name, isn’t it? There were so many of those petty nobles back then, full of their own inconsequence. The Baron and his Baroness were at the concert, and he recorded the program in detail. At least, that is what he purports to do. I can’t find any confirmation that he actually attended the concert. He may have been in the billiard room, and filled in the story later, from what the other guests told him. Still, he was at Lowenhoff—that much is certain.” She adjusted her bifocals so that she could read the text, and began to translate.

We, along with nearly all the Graf’s guests, entered the ballroom which was set for a concert with chairs in rows under the chandeliers, the elevated musicians’ platform occupied by the forte-piano alone. There was much excitement, for everyone had heard the rumors about Dziwny and the Graffin, which might or might not be true. Both the composer and the Graffin behaved impeccably.

You could also say

sinlessly

here

. Still, there can be no doubt that Dziwny has dedicated a number of his recent works to the Graffin, and she has been moved by them. The Graf has been losing patience with this state of affairs—the pun only works in English, of course—and he’s announced that he intends to be rid of Dziwny after the first of the year. He would dismiss him sooner but it would be difficult to find other musicians of high quality to engage so near the holidays, and there are many festivities scheduled to be held here. Also, of course, with his interesting reputation, Stasio Dziwny is still a composer who attracts a great deal of attention, all of it adding to the consequence of his patron, which the Graf von Firstengipfel would be reluctant to give up.

“That’s fascinating, of course,” said Vanessa, not entirely candidly. “But the actual program is where my interest lies.”

Nicola pretended to be slighted. “Oh, well, if that’s all—” She sniffed as she scanned down the page, and turned it. “Ah. Here we go.

Six Fugues on Themes of Handel.

That’s Dziwny’s own composition, as you know.”

“As I know,” Vanessa echoed, the complex passages coming to mind. Her fingers twitched as if sketching out the cadenzas.

“Then

Nursery Songs.

That’s by a student of Boccherini, according to the material here. It’s a flashy piece but essentially trivial; hardly anyone plays it anymore, but it has a certain appeal, with all kinds of ornaments and runs, just the sort of thing Dziwny was said to do better than any of his contemporaries, like his knack for fugues,” said Nicola.

“Knack?” Vanessa repeated.

“Oh, yes, I think so,” said Nicola. “He had the mental facility for them, they were his means to an end, not the end itself, a kind of magic trick that caught the attention of the public.” She looked down at the page again. “Anyway, there was an intermission; they served lemon ices and champagne. Then the

Grand Toccata and Fugue on a Polish Folk Song,

his newest work. He’d played it in public only twice before. He never finished that performance.”

“Is there anything in that journal that says when he actually did it? And what he actually did?” Vanessa could not keep the eagerness out of her voice.

“Yes,” said Nicola. “There is some mention of it.” Her frown became a scowl as she read the journal, translating as she went.

He had reached the second full statement of the central theme, a passage with a great deal of octave work in it, and when he got to the long fermata, followed by the repeated figure in the left hand, his right went into the pocket of his coat, and he drew out a small pistol. He put it under his right ear, and before anyone could properly discern his intent or move to stop him, he fired. He fell sideways, his head striking the keyboard, then there was consternation everywhere. The Graffin fainted and had to be taken from the ballroom by the Graf, who ordered that the room be vacated at once. It was an appalling incident, no matter what the reason may actually have been; with such a tragedy, the world will assume the worst, and will no doubt fix the blame on the Graffin. The servants were charged with the task of disposing of the body.

Or

reposing the body.

Some of these verbs are pretty irregular, even for early nineteenth-century German. It seems to say,

There was anxiety

or perhaps,

All felt anxiety because of this calamity.

Nicola put the journal down. “The rest is about the inconvenience of having to leave the next morning just as it was coming on to snow.”

“That’s pretty dispassionate,” said Vanessa.

“Well, the Baron was said to be a cool one. Still, watching a man blow his brains out can’t have been good entertainment, can it?” Nicola closed the journal. “I think he probably heard the event described, just because of the tone of it. His wife was most certainly in attendance, and she would have told everything to her husband; we know she accompanied the Graffin to her room and stayed with her for the whole night—she wrote a letter to the Graffin’s brother about the event, but put her emphasis on the Graffin, not on Dziwny.”

“Have you seen that letter?” Vanessa asked.

“Yes. It’s in a private collection in Salzburg. The owner allowed me to read it and copy down its text.” Nicola smiled faintly. “Would you like me to read it? I’m afraid the Baroness didn’t write very well, more like a third-grader than an adult—hardly surprising, given the state of women’s education at the time.” She reached out for the handle of the tallest file cabinet in the room.

“Never mind,” said Vanessa. “I get the picture.”

“It’s not a very pretty one,” said Nicola. “If you change your mind, I can make a translation and fax it to you while you’re on the road.”