Arabian Sands (27 page)

Authors: Wilfred Thesiger

We reached Bai five days after leaving Haushi. Seeing camels in the distance, Mabkhaut said, ‘That is bin Turkia’s camel and there is bin Anauf’s.’ We approached a ridge and suddenly a small figure showed up upon it. It was bin Anauf. ‘They come! They come!’ he screamed, and raced down the slope. Old Tamtaim appeared, hobbling towards us. I slid stiffly from my camel and greeted them. The old man flung his arms about me, with tears running down his face, too moved to be coherent. Bitter had been his wrath when the Bait Kathir returned from Ramlat al Ghafia. He said they had brought black shame upon his tribe by deserting me. We led our camels over to their camping place and there exchanged the formal greetings and ‘the news’. It was 31 January. I had parted from them at Mughshin on 24 November. It seemed like two years.

Only Tamtaim, bin Turkia, and his son were here. The others were near the coast, where there was better grazing. Bin Turkia said he would take the news to them next day. We slept little that night. We talked and talked, and brewed coffee and yet more coffee, while we told them of our doings. They were Bedu, and no mere outline would suffice either them or my companions; what they wanted was a detailed account of all that we had seen and done, the people we had spoken to, what they had said, what we had said to them, what we had eaten and when and where. My companions seemed to have forgotten nothing, however trivial. It was long past midnight when I lay down to sleep and they were still talking. Next day the others arrived and with them were many Harasis who had come to see the Christian. Some women also turned up. All of them were masked with visor-like pieces of stiff black cloth, and one of them was dressed in white, which was unusual.

1

There was much coming and going and much talk; only Sultan sat apart and brooded. My anxieties and difficulties were now over, but we still had far to go before we reached Salala.

We rode across the flatness of the Jaddat al Harasis, long marches of eight and even ten hours a day. We were like a small army, for many Harasis and Mahra travelled with us,

going to Salala to visit the Sultan of Muscat, who had recently arrived there. I was as glad now to be back in this friendly crowd as I had been to escape from it at Mughshin. I delighted in the surging rhythm of this mass of camels, the slapping shuffle of their feet, the shouted talk, and the songs which stirred the blood of men and beasts so that they drove forward with quickened pace. And there was life here. Gazelle grazed among the fiat-topped acacia bushes, and once we saw a distant herd of oryx looking very white against the dark gravel of the plain. There were lizards, about eighteen inches in length, which scuttled across the ground. They had disc-shaped tails, and in consequence the Arabs called them The Father of the Dollar’. I asked if they ate them, but they declared that they were unlawful; I knew that they would eat other lizards which resembled them except for their tails. But, anyway, there was no need now for us to eat lizard-meat. Every day we fed on gazelles, and twice Musallim shot an oryx.

We watered at Khaur Wir: I wondered how much more foul water could taste and still be considered drinkable. We watered again six days later at Yisbub, where the water was fresh and maidenhair fern grew in the damp rock above the pool. We went on again and reached Andhur, where I had been the previous year, and camped near the palm grove. Then we climbed up on to the Qarra mountains and looked upon the sea. It was nineteen days since we had left Bai. We descended the mountain in the afternoon and camped under great fig-trees beside the pools of Darbat. There were mallard and pintail and widgeon and coots on these pools, and that night Musallim shot a striped hyena. It was one of three which ran chuckling round our camp in the moonlight.

We had sent word into Salala, and next morning the Wali rode out to meet us accompanied by a crowd of townsfolk and Bedu. There were many Rashid with him, some of them old friends, others I had not yet met, among these bin Kalut who had accompanied Bertram Thomas. With him were the Rashid we had left at Mughshin, who told us that Mahsin had recovered and was in Salala.

The Wali feasted us in a tent beside the sea, and in the afternoon we went to the R.A.F. camp. My companions insisted on a triumphal entry, so we rode into the camp firing off our rifles, while ahead of us some Bait Kathir danced and sang, brandishing their daggers.

A leisurely journey with the Rashid

to Mukalla completes my survey

of this part of Arabia

.

I stayed at Salala for a week. I was busy writing up my notes, sorting out my collections, and arranging to travel with the Rashid to Mukalla.

I had come to Dhaufar determined to cross the Empty Quarter. I had succeeded and for me the venture needed no justification. I realized, however, that from the point of view of the Locust Research Centre my return journey through Oman was far more important than my crossing of the sands. To them the only justification for this crossing would be that it had enabled me to enter Oman. Had I tried to go there from the south the Duru would certainly have identified me with the Christian who had travelled the year before with the Bait Kathir and would have held me up. Coming from the north my rather unconvincing disguise passed muster because no one expected me to be European.

My own observations, and the inquiries I had made while crossing the Empty Quarter, had convinced me that there were few years when it did not rain somewhere in this area. The rain was usually slight, a few scattered showers; but little rain was needed to produce vegetation in the sands, and where it rained locusts could breed. I had seen a few locusts during the journey, some of them yellow, which showed that they were ready to breed. I had made notes of their colour, numbers, and direction of flight, and often bin Kabina and the others had secured me specimens, chasing and swatting them with their head-cloths. I had collected specimens of the plants that grew in the sands, and had compiled information about their distribution, and about recent rainfall. All this was useful, confirming what was already known or suspected as a result of my first journey to Mughshin, but I doubted that by itself

it would have justified the expense of this second expedition. However, from Oman I had brought back the information which the Locust Research Centre required. Dr Uvarov had thought that the river-beds which drained the western slopes of the ten-thousand-foot Jabal al Akhadar might carry down sufficient water to the sands to produce permanent vegetation there, and that in consequence the mouths of the great wadis might be outbreak centres for the desert locusts. I had found out that floods were rare in the lower reaches of the wadis, and that when they occurred they dispersed in the sterile salt-flats of the Umm al Samim, where nothing grows.

I enjoyed the days I spent at Salala. It was a pleasant change talking English instead of the constant effort of talking Arabic; to have a hot bath and to eat well-cooked food; even to sit at ease on a chair with my legs stretched out, instead of sitting on the ground with them tucked under me. But the pleasure of doing these things was enormously enhanced for me by the knowledge that I was going back into the desert; that this was only an interlude and not the end of my journey.

The Sultan, Saiyid Said bin Timur, whom I met for the first time, was very kind to me and gave me every assistance in arranging the next stage. He assured me that the restrictions which had been imposed on the R.A.F. did not apply to me, and that I could go anywhere and talk to anyone while I was in Salalala. This made it much easier to make my arrangements.

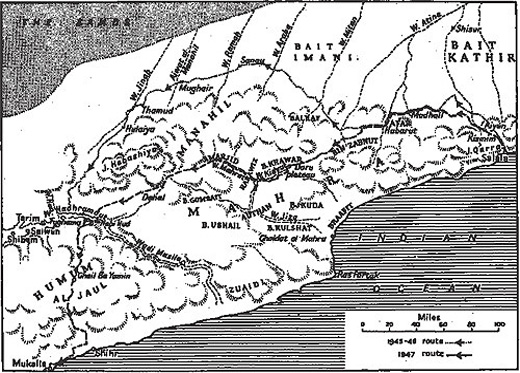

I now planned to travel to Mukalla in the Eastern Aden Protectorate and to map the country along the watershed between the wadis which ran northwards to the sands and those which ran southwards to the sea. A map of this area, together with the one which I had made the year before during- my journey to the Hadhramaut, would establish the outline of the unknown country to the west of Dhaufar.

I arranged with bin Kalut that he and a party of Rashid should go with me to Mukalla. We agreed that I should pay for fifteen men, as I had done the previous year, but that the Rashid should settle among themselves how many actually accompanied me. A large force of Dahm had raided the Rashid and Manahil two months before, capturing many camels, and my companions were afraid that we might

encounter other raiding parties near the Hadhramaut. Bin Kalut undertook to find the necessary

rabias

from the tribes whose territory we should pass. I meanwhile paid off the Bait Kathir, except for Mabkhaut, bin Turkia, and his son bin Anauf. Musallim could not come with us because we should be travelling through Mahra country and, having killed one of them, he had a blood-feud with that tribe. AI Auf, bin Kabina, and the three Bait Kathir were to come, in addition to the party which bin Kalut was collecting.

On 3 March bin Kalut and about sixty Rashid turned up in the R.A.F. camp. The airmen moved about among them taking photographs and watching them loading their camels. These airmen were my fellow countrymen, and. I was proud to be of their race. I knew the essential decency which was the bed-rock of their character, their humour, stubbornness, and self-reliance. I knew that if called upon they could adapt themselves to any kind of life, in the desert, in the jungle, in mountains, or on the sea, and that in many respects no race in the world was equal. But the things which interested them bored me. They belonged to an age of machines; they were fascinated by cars and aeroplanes, and found their relaxation in the cinema and the wireless. I knew that I stood apart from them and would never find contentment among them, whereas I could find it among these Bedu, although I should never be one of them.

A large number of Bait Kathir and other tribesmen camped with us that night at Al Ain. Musallim was among them, having come to see us off. Rather apprehensively I asked bin Kalut how many of these people were going with us to Mukalla. He reassured me by saying that there would be only thirty Rashid, as well as my own party and

rabias

from the Bait Khawar, Mahra, and Manahil. We then divided up the flour, rice, sugar, tea, and coffee, which I had provided, and also the three camel-loads of Omani dates given to me by the Sultan. I hoped that we should have plenty of food even if we travelled slowly and took two months to reach Mukalla. I was tired of being hungry.

Bin Kalut was a striking person. Short, thick-set, and immensely powerful, his body was heavy with old age, so that he

moved with difficulty, and rose to his feet only with a laboured effort and after many grunted invocations of the Almighty. His speech, movements, and gestures were very deliberate. He had a broad rugged face and a jutting nose, steady eyes, a wide mouth, and a heavy grey beard, and he was completely bald. He seldom spoke, but I noticed that when he did no one argued. His son Muhammad, who was half-brother, through his mother, to Salim bin Kabina, was with him; a young man, heavily-built like his father, amiable but rather ineffective. There were many Rashid here who had been with me the year before. Musallim bin al Kamam was among them; a lean middle-aged man with a quick receptive mind and a relentless spirit which drove him so that he was the most widely travelled of the Rashid, and the most intelligent. I had liked him greatly when we had been together, and had found him an amusing companion, quick to tell me anything that he thought might interest me. He was very self-controlled and I never heard him raise his voice. Unfortunately he could not travel with me now. A year before, he had concluded a two-year truce with the Dahm which this last raid had violated. Now he was going to demand the return of the Rashid camels that had been lifted.

Until recently, the Saar who live on the plateau to the north of the Hadhramaut had been the main enemy of the Rashid, the Bait Kathir, and the Manahil, but during recent years the Dahm and Abida from the Yemen had taken their place as the most formidable raiders in the southern desert. These two tribes were not Bedu but villagers living in the Yemen foothills. It was an inversion of the usual role that the Bedu raided the settled tribes, and bin al Kamam and others of the Rashid assured me that the Yemen authorities in the Jauf supplied these raiders with the arms and ammunition which gave them their superiority over the desert tribes. There seemed to be little doubt that the Yemen government encouraged these raids in order to embarrass the Aden government by increasing the chaos in the desert north of the Hadhramaut.

In 1945 a large force of Manahil under the leadership of bin Duailan, who was nicknamed al Bis or ‘The Cat’, had set out to raid the Dahm. Unfortunately they had not reached the

Dahm villages, but instead had attacked an encampment of the Yam, had killed several of that tribe and lifted a large number of their camels. The Yam were Bedu, owing allegiance to Ibn Saud, and their homelands were near Najran. When they were attacked they were grazing their herds in the desert on the Yemen border. This was not the first time that the Yam had suffered from raiders from the Eastern Aden Protectorate, who had intended to attack the Dahm, but had been diverted by the prospect of easier loot encountered on the way. When I was in Jidda in the summer of 1945 the British Ambassador had questioned me about these raids and had told me that Ibn Saud had threatened to loose his tribes on the Hadhramaut if they continued.